On Constancia de la Mora and the Plight of Writers in Exile

Soledad Fox Maura on Rediscovering the Fascinating Story of Her Distant Relative

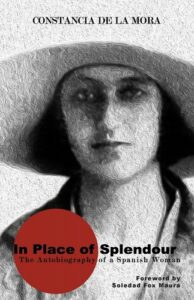

I remember seeing Constancia de la Mora’s In Place of Splendour: The Autobiography of a Spanish Woman as a small child, and considering it something of a marvel. My mother, who was a second cousin of de la Mora’s, had a first edition. Though I was still too young to read it, I knew it was old and special. I had flipped through the first pages a few times and was almost embarrassed by the very personal tone of the author’s descriptions of her childhood in Madrid. That is as far as I got. I did not know it was a book about the Spanish Civil War.

It was hard to imagine that we had a relative who had written an autobiography in English, published in the United States. I hate to say this now, but it was especially hard to believe that a female from my family had written a book. It was, frankly, cosmopolitan enough in our milieu for women to own and read books in other languages, to write them was simply out of the question.

In 2001, I started to teach a course on the Spanish Civil War. I became particularly interested in Spanish Republican (not to be confused with the North American party of the same name) narratives about the conflict. How had they survived the war, and been able to leave Spain safely? Where had they managed to relocate, and how had they adjusted to their new—often permanent—lives, in France, Russia, Mexico, and the United States? How did they make a living in a foreign country, and, in many cases, in a new language?

It was, somehow, through the disparate threads of these complicated lives that the Spanish Civil War and its consequences began to make sense to me. Through the specific and personal, I was finally able to start to piece together aspects of an intensely complicated, international, three-year war. It was through focusing on women’s experiences during the war and postwar that In Place of Splendour came to my attention again.

I was surprised by the beauty of its structure, narrative flow, and her candid, intimate voice when discussing her childhood, her failed first marriage, her socially condemned divorce, passionate love for a famous pilot (who she also married), and her exceptionally important role during the war. Yet despite the clear voice that told her story, Constancia was still mysterious in so many ways. In Place of Splendour had no foreword, no acknowledgements, no photos. I had no idea what the author looked like, or where and how she had died. Why had she written a memoir at the age of 32? What had become of her life? Why had she vanished? Why hadn’t she written more books? How and why did Constancia de la Mora set out to publish her life story in English?

Making the work of Spanish writers available in English now is an incredibly valuable feat of archeological digging, preservation, and inclusion.

In pursuit of these fundamental questions, I spent the next few years of my life doing research on her life drawing on disparate materials from personal, state, and university government archives in Spain, the United States, Mexico, Holland, and Russia. The outcome of this research was my biography of Constancia de la Mora, published in England in 2007, and in Spain in 2008, and re-released in 2017.

She was born in 1906 into a powerful family in Madrid and was raised to be a socialite. She learned to play tennis, ride horses, attend debutante balls, and shop in Paris. She moved between the family home in Madrid, a hunting estate in Segovia, “La Mata”, and summer resorts such as San Sebastián, in the north. She was an imposing tall figure, with large dark eyes, a luminous smile, and a confidence that came from the power in her background, and her own strong personality. She had two female siblings. Marichu was a fair-haired beauty who was politically to the right and known for her style. Regina, who Constancia was closest to, was warm, intelligent, witty, and also conservative.

According to her memoir, the happiest time in Constancia’s young life was the period she spent studying in Cambridge, England. She loved the English language and culture, and above all cherished the independence she saw in the lives of the young women around her, one that she hoped to emulate. She repeatedly wrote to her parents to ask for permission to stay on and find herself a job. Her parents responded negatively and swiftly. She was returned to Madrid to get back to her real duty: finding an appropriate husband.

Marriage was the first major step for young women like Constancia in the 1920s, and by the time she met her husband to be, Manuel Bolín Bidwell, she was a bit past the conventional age—all of twenty years old when they wed in 1926. A salient detail about the marriage’s early days from Constancia’s memoir is that during their honeymoon in Italy she bought herself a French Bulldog because she was so lonely. Though she gave birth to a daughter, Luli, in 1927, the marriage stifled Constancia and her wish to have a life of independence.

The young couple grew apart, and by 1931, they were legally separated. Constancia did something revolutionary for a young madrileña wife and mother: she moved, with Luli, to a home of her own, and she realized her dream, cherished since her days in Cambridge, of finding a job.

She started to savour her freedom, to make new friends, and this exciting period coincided with the election of a new Republican government in Spain. The ousted King, Alfonso XIII, was forced into exile. She and Luli moved into an apartment. She became close friends with Jay Allen, Madrid correspondent of the Chicago Tribune. Allen was her first American friend, and she would learn a great deal from him. He was a political reporter, and would broaden Constancia’s outlook on the United States, democracy, and Spain. She also became very close to the cosmopolitan Zenobia Camprubí during this period. Zenobia was a welcome change of pace from the women Constancia had known in her youth. She was half Puerto Rican, and had been educated at Columbia University. She came from a newspaper family in Puerto Rico, and her brother was the owner of the major Spanish language paper in New York City La Prensa. She was married to the poet Juan Ramón Jiménez, and had her own shop, “Arte Popular,” which sold traditional artisanal products she had sourced from all over Spain. Allen and Camprubí would have a definitive and lasting influence on Constancia’s future. If it seems life journalists are going to have a key role in her story, read on.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, it was during this time of new found freedom that Constancia met the love of her life: Ignacio Hidalgo de Cisneros. Ignacio was a handsome pilot, and flying and the ideals of the new Republican Government were his key passions. So were women. Constancia’s sister Regina, who introduced the couple, warned Constancia not to fall for him because he had left a string of broken hearts in his wake. But the die was cast and Constancia and Ignacio became inseparable. She would obtain one of the first divorces of Spain’s history in order to marry Ignacio in a civil ceremony. Ignacio became a dedicated—and lifelong—member of the Communist party around this time, though Constancia makes no mention of Communism per se in her memoir. We can only guess how quickly she was exposed to his political commitment, and to what extent she became a fellow traveler. We do know from Ignacio’s own brilliant memoir, Cambio de Rumbo, that going to watch Battleship Potemkin was one of their first dates.

When Ignacio was appointed Spanish Air Attaché in Rome and Berlin, the couple caught their first glimpse of the sinister forces awaiting their own country.

They arrived in Berlin in early in 1935. The first Nazis Ignacio met with assumed he was a Republican only in name, and shared their plans with him. They requested aerodromes in Morocco and the Spanish Sahara, permission to build bases for their Zeppelins in Spain and the Canary Islands, and to create vast radio networks throughout the country. In exchange, they would completely modernize the Spanish air force, making Spain ready for a coup. Ignacio warned the Republican government, but was told to calm down. Sadly, Constancia and Ignacio had seen, up close, what lay in store for Spain.

In September 1935 they moved back to a Madrid that was restless with political tension. Constancia’s Republicanism put a damper on her relationships. Her father tried to give her and her siblings some of his land in a way that would circumvent the Republic’s Agrarian Reform laws, and she adamantly refused to accept it. The rift with her family, though they had accepted the charming Ignacio with open arms, was quickly intensifying. Her dear friend Zenobia, in days past much more worldly and forward thinking than Constancia, was politically neutral and they quickly lost touch, forever. Jay Allen was one of the few friends who continued to fight for Spain’s democracy, even after the war was over.

Constancia was thirty years old when the Spanish Civil War broke out on July 17-18 of 1936. As historians have pointed out, the war in Spain paradoxically brought about unprecedented opportunities for women to have active roles in what had traditionally been exclusively masculine spheres. Initially, Constancia began helping children who had been orphaned or separated from their parents. Ironically, she was familiar with this kind of work from her days as a socialite who like so many women in her class made the de rigeurappearances at orphanages to show their charitable side. But the context was completely different, of course, and now she was in the trenches. During the war, she and Ignacio were often separated, and his health suffered drastically. She was also separated from her daughter Luli, who like many other Spanish Republican children were sent to Russia for safekeeping during the war.

Ignacio and Constancia hoped that if Fascist forces attempted to overtake Spain, their government would be defended by the other democracies. When 27 countries, led by France and England, signed a non-intervention act, effectively an embargo on selling arms to Spain, in August 1936, the Republic was devastated. The United States did not sign, but maintained an isolationist policy. In her memoir, Constancia returns time and again to the fact that Britain and the United States, which she hoped would be friendly, democratic governments, were quick to taint the Spanish Republic as “red”, and with that justification, abandoned the Republic to Franco and his military rebels backed by Mussolini and Hitler.

It was urgent for Spain to show English speakers that democracy was at stake in Spain, and thanks to Constancia’s energy, eloquence, and fluent English, she was made Head of the Republican Foreign Press Office. In this position she worked with countless foreign writers, amongst them, Ernest Hemingway, André Malraux, and photographers like Robert Capa and his girlfriend Gerda Taro (who was tragically killed during the war in Spain). Her goal was to make sure the international press communicated just how unfairly Spain’s democracy had been treated, and how exceptionally they were rallying, alone and only with the help of the International Brigades, to fight off Fascism.

Her public relations mission took Constancia to the United States in January 1939. It was part of a belated and desperate campaign to appeal to the White House to finally lift the arms embargo. She sailed to New York and first landed at Jay Allen’s beautiful home on Washington Square. The plan was to extend Constancia’s role as the face of the Republic to the English-speaking world. She would give talks, attend anti-embargo rallies, socialize, and make a beeline for the White House. Thanks to Martha Gellhorn (war correspondent and soon to be Mrs Ernest Hemingway), Constancia was received by Eleanor Roosevelt with whom she had an extensive correspondence about the war in Spain. The first lady was staunchly on the side of her new Spanish friend.

Spanish lives and literature—male or female—don’t yet have the exposure they deserve in English.

In Place of Splendour, the memoir at hand, was part of the publicity campaign. I believe the idea for the book was hatched by Jay Allen, who brought in Ruth McKenney, a left-leaning bestselling author, to give the narrative its beautiful structure and language. The story is Constancia’s, and she lent her biography to the cause of the Spanish Republic so that the world could learn, from the account of a first-person woman—a wife and mother—how brutally unfair the war in Spain had been. Constancia was the ideal poster woman for the Republican appeal because she had been born into wealth and privilege, but chose to fight for democracy and freedom. Her story has all the great elements of a conversion narrative, and the book, published by a major press, Harper & Row, in December 1939 was on the The New York Times Christmas books list. Constancia had the United States in her pocket. She was received as a celebrity, a beacon of democratic ideals, and a beautiful Spanish señorita. This impassioned personal and political narrative was a New York Times bestseller that was translated into many languages including Spanish, Italian, and Russian. The fact that the book was written directly in English was a plus for the author and her story. She was almost “one of us” from the Anglo perspective. Almost, but not quite.

Though In Place of Splendour came out eight months after the end of the Spanish Civil War, and three months after the start of World War II, it was conceived before the war in Spain ended, in the heat of the moment, and the final draft was wrapped up in the summer of 1939. The book’s publication was too late to change the direction of the war, but its success showed how many people sympathized with the Spanish Republic, despite their government’s embargos and isolationist policies.

The memoir and Constancia herself were quickly repurposed to be used to drum up support for the close to half a million Spanish Republican refugees stranded in dismal conditions, primarily in France. The German occupation of France only made the fates of these exiles dramatically worse, and groups around the world gathered to bring attention to their plight and send them basic supplies. World War II quickly eclipsed the fate of these dislocated Spaniards, and the Cold War, and Franco’s ever enduring dictatorship and complicity with the Western Allies made sure the subject of Spain’s refugees fell into oblivion.

Right after In Place of Splendour was published Constancia met Ignacio in Mexico for a much-needed reunion and some rest. Luli was still in Russia, and despite all the pressure Constancia tried to leverage, she would not be free to travel and join her mother until after the end of World War II.

When she prepared to return to the United States to resume her speaking schedule and her campaign for the Spanish refugees and against Franco, her entry visa was denied. Not even a personal plea to Mrs. Roosevelt could provide a solution. In the immediate aftermath of the war, there had been tensions between the Spanish refugee aid groups in exile, and Constancia’s name had been associated with the Communist group. This was enough bad press for her, and Ignacio, to be denied entry to the United States.

Unable to return to Spain or New York, she and Ignacio settled in Mexico City, amongst other Spanish exiles and international friends like Pablo Neruda and Tina Modotti. Ignacio, used to expertly flying dangerous missions, was at a loss after the war. Their marriage deteriorated, they divorced, and he eventually resettled in Warsaw, and later Bucharest, using Communist Party connections to help him secure housing and jobs. He remained a devout Communist for the rest of his life, and was buried in 1966 with full Rumanian military honors. His Spanish Catholic family disinterred him and re-buried him in the family crypt in Vitoria, Spain in 1994.

Constancia built herself a beautiful house in Cuernavaca. In 1947, she broke all ties with the Spanish Communist Party. It seems that she was kicked out, however, as I explore in my biography, it is doubtful that she had much interest in remaining active.

When World War II finally ended and the allies left Franco in power, most Spanish exiles felt they had lost the Spanish Civil War yet again. Spain was largely forgotten by the world until after Franco’s death.

By 1947, Constancia had her daughter with her in Mexico, and was trying to get different literary and artistic projects off the ground. She also earned money by taking wealthy American tourists around Mexico and Guatemala. She loved Mexico, and knew all the best local artisans and the most beautiful places to go.

It was during one of these trips through Guatemala, by car, with a group of Americans (and the English writer Nancy Johnstone) that the brakes failed on a steep hill. Nobody was hurt in the accident except Constancia, who was killed instantly. It was January 26, 1950, the eve of her 43rd birthday.

As I look back on Constancia’s life and death nearly twenty years after I first started working on these subjects, I still cannot firmly clear up the enigmas that surround her. It was rumored after her death that she had been murdered by the Spanish Communist Party, and/or by the FBI. My sense was that her Communism was not lasting, and that she originally thought that Russian support would help Spain remain democratic. She was completely seduced by Ignacio and his ideology, but I think of her as a committed Republican, who had hoped for a very different outcome for her country, and definitely not a Communist outcome. I’ve seen her referred to as a “fanatic” when she was a Communist at most accidentally, and only for a period of her life. I have never heard diehard Ignacio referred to with anything but praise, from all sides. A “dashing aristocrat”; a “pilot.” It seems to me that women are rarely judged with the same yardstick as their male counterparts.

It is also true that Spanish lives and literature—male or female—don’t yet have the exposure they deserve in English, even when they were written in English, like In Place of Splendour. It is easy to assume that entire cultures are unknown to us because so much goes untranslated, but in the case of Spain, its own political history isolated its people for decades, especially those who were in exile. And obscurity has a knack for self-perpetuation. Making the work of Spanish writers available in English now is an incredibly valuable feat of archeological digging, preservation, and inclusion. Perhaps one day de la Mora’s name may be as familiar to some as Mitford, Woolf, Stein or de Beauvoir. Her oeuvre is much smaller, but her life no less exceptional and worthy.

Constancia was a vital, confident woman who was ahead of her time, and for that she paid a very high price. She lost her family, her country, the love of her life, and her daughter for nearly a decade. Then she lost her life.

When I published my biography in 2008 I cherished a hope that In Place of Splendour would one day be published again in English. Constancia de la Mora’s story is fascinating and reflects the tensions of 20th century politics that have spilled over and intensified in our own time. It is uniquely difficult for exiled writers to recover their voices. Without a country behind them to bolster them, curate their work, and revive their legacies, where is their place in history?

Some of the best days of Constancia’s life were spent in England, and it is fitting that her voice be revived there by The Clapton Press; out of print in English since 1944—after seventy-seven years of silence—the book is accessible to English readers everywhere.

Read an excerpt from In Place of Splendour: The Autobiography of a Spanish Woman here.

__________________________________

From In Place of Splendour: The Autobiography of a Spanish Woman by Constancia de la Mora, with a foreword by Soledad Fox Maura. Used with the permission of Clapton Press.

Soledad Fox Maura

Soledad Fox Maura is a professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature at Williams College. She is the author of Exile, Writer, Soldier, Spy: The Life of Jorge Semprún, listed as one of the top “literary lives” by the Wall Street Journal in 2019. Her first novel, Madrid Again will be published by Arcade Books. She is on Goodreads and Instagram as Soledad Maura.