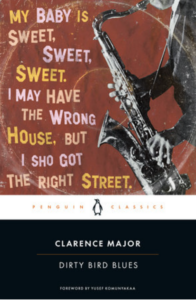

On Clarence Major’s Enduring Portrait of the Blues, Dirty Bird Blues

Yusef Komunyakaa Introduces the 25th Anniversary Edition

Clarence Major knows and feels the blues, and his protagonist in Dirty Bird Blues, Manfred Banks, better known as Man, is a folk poet and singer who measures the heart line with a humbling down-home voice and an insinuating harmonica, as he conjures Big Bill or Charley Patton. Man’s daily life is riddled with bluesy innuendos, primed by half-pints of Old Crow (“dirty bird”) whiskey. His friend and accompanist, Solomon Thigpen (Solly), is his drinking buddy, who clutches his guitar like a half-lost lover. Both men seem indebted to Old Crow when they jam. But Man’s lyrics are always searching for lines and rhymes that delve into ultra-realism and nature, and at times seek higher ground, daring to break the grip of a troubled heart and mind.

The author, born in Atlanta, Georgia, moved with his mother to Chicago when he was ten. First drawn to painting, then to poetry, this virtuoso compiled two dictionaries of African American slang, and it is understandable how Major’s intimate engagement with slang may have influenced the folkloric tone in Dirty Bird Blues. Under the shaping hand of such a discerning disciple, the lived and imagined flow together without missing a beat—feeling and living the blues. Major astutely experiments with his verbal arsenal in this one-of-a-kind novel. This man knows how to make the sounds and cadences in language actually swing.

Dirty Bird Blues opens on the South Side of Chicago on Christmas Day, and the reader is immediately in the midst of urban drama and life-threatening realism. Hardly any time passes before Man finds himself in the lobby of a Black hospital, his wound of buckshot pellets being bandaged by an inquisitive Black nurse, before he’s taken outside and handcuffed by two relentless Black cops he nicknames under his breath Bullfrog and Lizard. They laugh at his country southern speech and then take him on a ride, roughing him up in the back seat of their police car. Remnants of the Great Migration resound, as the author captures urban destitution and defeatism.

While Major reveals damaging constructs deep within the cultural psyche, he is never didactic, for he remains true to the voice of his protagonist. A thoughtful pacing of the novel exacts the movement of a man’s life, of his mind. Man’s lyrics—as they are conceived and sung—break up passages on the page. Also, Major uses italics to carry the reader into dimensions of a mind. There are seven italicized passages, the first a letter from Man’s sister, Debbie, dated November 12th, 1949. She invites her brother to move to Omaha, Nebraska—to give it a try. But shortly after the letter we begin to encounter Man’s lucid dreams, also cast in italics—six dreams throughout the novel.

These interludes seem to function as signposts for a life in flux, in motion. These near-prose poems tap into a man’s inner life—the internal voice of an initiated witness. In this sense, the essence of the blues fits hand in glove with the main character’s personality, his voyage. Man, in measured thought, unearths elements of his life and attempts to reckon with the almost unsayable delivered as the blues. What the old ones may have called “trials and tribulations”—what Louis Armstrong sang as a question to the cosmos: “What did I do to be so black and blue?”

Major dares to articulate the social politics of the varied hues of skin color within the Black community, highlighting complexities, especially among the womenfolk, and quickly moving on, like glancing blows of insight. Yeah, just troubling the keys. The storyteller is praised in Dirty Bird Blues, and Major skillfully practices what his characters preach.

Undeniably, at the heart of storytelling is ritual. At first it seems that drinking Old Crow is the only path to blues lore. But Man may also feel he is undermining himself through a slow kill, that a godsend is his wife, Cleo, and daughter, Karina—their familiar love and strength. Yet his friendship with Solly is based on their daily cavorting with the dirty bird—as if a communion ritual by two serious drinkers.

The secondary characters in Dirty Bird Blues humanize the earthy landscape of this novel. We think we know their thoughts. The blunt descriptions of characters become the book’s raw poetry. They are real. Man surveys the mental and physical terrain, as if to know is a survival mechanism.

Major’s character, Man, knows his pursuit of the blues—as if a sacred hymn—is not a duty but a calling, the only way he can survive what he witnesses as a Black man.

The reason for his questing gaze through lyrics is almost a mystery until near the end of the novel—so well placed. Racial slurs throughout Dirty Bird Blues are taken for granted. Verbal assaults seem accepted reality until a flashback pulls everything together, with Man’s family slinging verbal arrows—a duel of children against children. His acute memory recaptures a life-shaping moment when he overhears his uncle Aloysius saying to his father, Quincy, that Manfred is ugly because he’s black. His father does not seem appalled by his brother’s insult. Hereupon, given Man’s propensity for posing questions in his lyrics, the reader may wonder if he ever questions why his father, Quincy, so often beats his mother, Charity—if it has anything to do with the hue of her skin. Hadn’t Man and his older brother Billy fought their father to defend their mother? But time has passed. Billy was sent off to Korea. The reader wonders, is Billy—brother and savior—alive or dead?

Yes, perhaps Manfred’s blues began when he was a boy, when his cousins, Nona and Netty, who were bigger than him, took a cue from their father, Aloysius, and began their rehearsed ridicule. He remembers Nora saying, “We got pretty light skin.” Man recalls succinctly each put-down and gesture. Is this the beginning of his existential loneliness? His indelible memory would be a mind-jail if he didn’t own a blues harmonica and a beautiful strong voice. Man is an artist.

James Baldwin speaks about feeling condemned as a writer, as if cursed to traverse the nine rings of Hades. But Major’s character, Man, knows his pursuit of the blues—as if a sacred hymn—is not a duty but a calling, the only way he can survive what he witnesses as a Black man. His psychic reckoning is to hone his chops, creating lyrics that jibe (jive), and at times even summon laughter. His weekend gigs at the Palace are almost spiritual.

Major lets his characters speak language he has perhaps heard in life, and at times he even lets them condemn themselves. He does not wipe downfalls clean from the slate. When the young men on cleanup crew are playing the dozens at Sears during the night, he does not diminish the harsh reality of their put-downs and outlandish behavior risen out of self-hatred. This blues novel exposes social and psychic turmoil in corners of Black America—the pathos passed down through generations.

The friendship between Solly and Man grew shaky when Man stopped drinking whiskey and switched to coffee or soft drinks. It wasn’t long before they got into fisticuffs. And after the bloody fight ended, they stayed apart from each other. One day—unable to bear the silence any longer—Man goes searching for Solly. He has to make things right between them. But he learns that Solly has returned to Chicago.

Multidimensional and experiential in its structure, Dirty Bird Blues is steadfast in its focus and spirit, propelled by the protagonist’s quest. Man isn’t merely a bluesman, but he is an artist—always engaged, like a John Coltrane—not satisfied with the mere fingering of the elemental strings of his existence but determined to see into the mystery of his being, as well as gaze up at the everyday sky or seek out a woman’s eyes. Not only is the reader gifted with Man’s thoughts and observations as blues lyrics throughout Dirty Bird Blues, but also some narrative passages of insinuation are playfully structured and rhymed. We are coaxed into Man’s world.

The last section, which is composed of six short sentences—without poetry or rhyme—possesses a clarity that is transformational. To sing the blues is to go through the psychological weather of glancing blows, even at times de-spiritualized—not to go around or attempt to sidestep black-and-blue reality. And here we feel and know Man is a bluesman about to take a step beyond the cusp, as his ascent begins through earned love for his wife and daughter.

__________________________________

Forward from Dirty Bird Blues by Clarence Major. 25th Anniversary Edition forthcoming by Penguin Classics February 2022.

Yusef Komunyakaa

Yusef Komunyakaa's books of poetry include Taboo, Dien Cai Dau, Neon Vernacular, for which he received the Pulitzer Prize, Warhorses, and The Chameleon Couch. His most recent collection is The Emperor of Water Clocks. His plays, performance art, and libretti have been performed internationally and include Saturnalia, Testimony, and Gilgamesh. He teaches at New York University.