On Choosing to Write in a Second Language

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho goes the way of Nabokov and Hemon

I never meant to write in English. Most of the decisions that we, the recent arrivals, make are driven by necessity rather than choice. More often than one might think, we’re tax preparers dreaming of going back to acting or teaching one day, cab drivers who used to practice medicine in other parts of the world. We switch professions or shed mother tongues as reflex actions—the survival instinct bullying us forward into supernatural confidence, tricking us into believing we’re more malleable that we’ve ever been.

I was 35 when I first put pen to paper in English. It was the fall of 2008 and I’d been awarded a journalism fellowship at Stanford. In the four years I had lived in Austin, Texas, my use of English had remained colloquial. During the day I worked for a chain of Spanish-language newspapers, while at night I’d continue to write, in my native language, the novel I’d started years ago—and which had yet to draw the attention of any agent or publisher back in Spain, where I’d lived for years, or Mexico, my home country. It was an unpublishable manuscript plagued with flaws, but I lacked the ability, then, to see that.

After years managing teams in shrinking newsrooms, suffering through Power Point presentations, surviving yearly rounds of layoffs, all I wanted was to go back to writing. My goal at Stanford was to become a better storyteller in both fiction and nonfiction, but it seemed the only way to achieve it was by choosing English—the university didn’t offer writing classes in Spanish.

The first course I enrolled in was a nonfiction workshop for undergraduates. Our initial assignment was a self-portrait of childhood. “The boy in the picture would always seem to be there like a non-invited guest,” mine began. “Arms tightly attached to the body, big ears sticking out of the head, and the head itself pressing down the neck, as if wishing it could be retractable, like that of a turtle, and be actually able to hide the face and the trembling smile away from the photographer’s acceptance/lens.”

The reaction from my professor and classmates was unanimously wild. They praised my idiosyncratic phrasing, the playfulness of my language, the droll absurdism of my deliberately self-conscious writing. If this was a tactful, compassionate way to address my grammatical mistakes, the baffling length of my crippled sentences or the lack of adroitness at my use of some words, I didn’t notice. I hadn’t taken classes in America before, had never been exposed to the healing powers of positive reinforcement, and I was exhilarated.

Madly encouraging as it was, such feedback didn’t ease my sense of failure. Why is it uninvited instead of non-invited? Why should I replace tightly attached to with pressed against? I was clueless. The experience of writing in English was akin to swimming underwater without goggles, eyes wide open: everything’s a blur, you only see the color and contour of the objects—the words if you will—in front of you, but the crisp, total understanding of their magnitude remains elusive.

Weeks into my first semester, we read an essay in class about a girl from Sacramento moving to the East Coast for the first time. “I can remember now…” I read in the opening of “Goodbye to All That,” “when New York began for me, but I cannot lay my finger upon the moment it ended, can never cut through the ambiguities and second starts and broken resolves to the exact place on the page where the heroine is no longer as optimistic as she once was.”

A writer I didn’t know had penned the piece in 1967. It was love at first reading. The incantation of Joan Didion’s rebellious use of language riddled me like a spell, a lash of liberty, but I couldn’t figure out why. Only later did I realize that “Goodbye to All That” had resonated so deeply because the girl landing in a foreign realm was me. English was my New York, its grammar and idioms and irregular verbs the haunters of my broken resolve. Joan Didion had managed to depict my experience moving to a new language like she’d inhabited my brain.

The overall reception to my work at Stanford persuaded me to give creative writing a serious try—in English, that is. That summer I was admitted to a renowned writers’ conference in Vermont. A few journal editors asked me to send them work, a couple of New York agents were eager to read the memoir I was writing. Not only did that encouragement not dissipate the fog—it turned into pressure. The conviction that my sentences sounded odd and hollow grew firmer than ever. The only way to succeed, I resolved, was by expressing myself properly, without mistakes.

A few months later, after a failed attempt to write my memoir in English like a native, followed by gentle (but succinct) rejections from agents, I was unemployed and incapable of finishing the fiction sample I needed in order to apply for an MFA. At a secondhand bookstore I stumbled upon a copy of The Year of Magical Thinking. I hadn’t read Didion since leaving Stanford, but immediately felt her book was there waiting for me. I devoured it with the fervor of a troubled believer. Hope was waiting for me on page 140:

“I never actually learned the rules of grammar, relying instead only on what sounded right.”

For some reason I’ve never unraveled, Didion’s cadence had always felt so similar to what sounded right in my head. Now she was there, sharing her secret like a sanction of sorts, reassuring me that if she’d mastered her style by following her instinct, I could possibly too. We, the recent arrivals, sometimes have no option but to grow audacious and bold.

During my first semester at the MFA I was admitted to the following year, I took an English Grammar course for undergraduates—I still felt I needed to know the rules. But reading Joan Didion in my darkest hour helped me realize that I’d only manage to grow my voice by embracing my idiosyncratic blemishes, by marrying the ambiguities of my phrasing with the shatterproof elasticity and unmatched generosity of my second language, by making a virtue of the droll absurdism of my alien heart, by conjuring beauty out of the haze, by making myself at home in the blur.

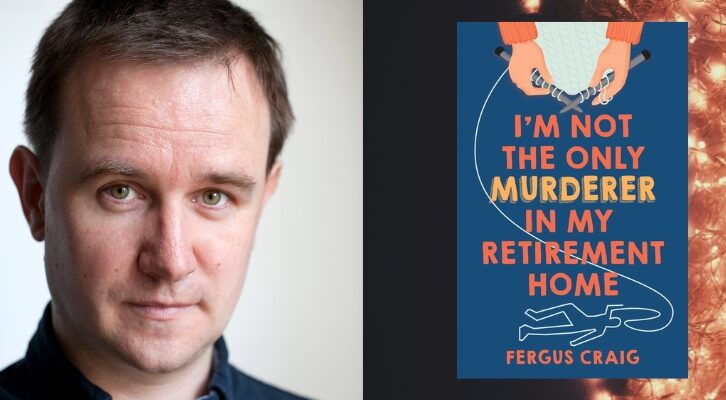

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho’s collection of stories, Barefoot Dogs, is out now.

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho has an MFA form The New Writers Project at the University of Texas at Austin, where he was awarded the Michael Adams Thesis Prize in Fiction. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, StoryQuarterly, Poets & Writers, Kirkus Reviews, and Etiqueta Negra. His collection of stories, Barefoot Dogs was published by Scribner in April.