On Celtic Storytelling, From the Bardic to the Mythic

Martin Shaw on Growing Up Christian with a Pagan Underbelly

I grew up in a Christian house with a pagan underbelly, and found the two were not quite as oppositional as some may expect. My father is a preacher but with a great love of the wily, strange and magnificent world of folktale and myth. Due to financial scarcity I was raised without television, phone or car. This forced me to make a vivid ally of my imagination.

Thirty years after my birth I would find myself hitting the cobbles and going from town to town pursuing a very ancient vocation, that of an oral storyteller. It seems that when humans imagine, they tend to imagine in story. Stories—and specifically the images within them—have a kind of power that the shrill ring of statistics or concept can’t quite possess.

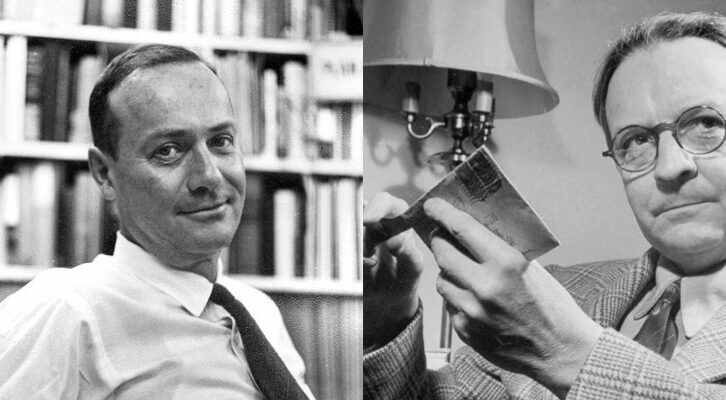

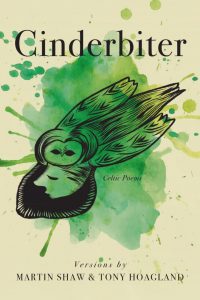

About ten years ago, I fell in with the poet Tony Hoagland. It was love at first sight for both of us. His extraordinary wit, pathos and sheer, wayward intelligence made loving his work just as easy. Tony read a version of a Hebridean story I was working on—I call it Cinderbiter—and suggested breaking the prose into stanzas. For all intent and purposes the words remained the same, but choreographed into this lively new shape by Tony. It was such a pleasure that a book emerged from it, from epic story to nifty little lyric pieces.

As we have been clear, we venerate the work of diligent translation, and this is not what we did. These are versions, not translations. Attention here is paid as much to energetic feel as literal transcribing. Also, some of the stories don’t have any kind of particular literary pedigree, but have passed from jaw to jaw of Gaelic and British storytellers down the centuries.

Celtic storytellers have endured and enjoyed a roguish reputation through the millennia.

So other than rough account, there was no lineage to necessarily work out of. Some of these tales I learned by campfire, tramping home in the moonlight across the moors, or from the grinning mouth of a Brixham fisherman. Oral storytelling is a way of wondering on the tongue. Thinking out loud.

Celtic storytellers have endured and enjoyed a roguish reputation through the millennia. Their place is rarely the court of the high bards, rather the firesides of taverns and farmhouses. Their task is not to perfectly preserve great, rigid tracts of history for the financial benefit of their lordly patrons, but to spin the gossip of the hedgerows, the magic of fairy, the grief of the village to their attentive and hearth gathered listeners.

The work Tony and I did moved between both traditions—bardic and storyteller. These days very few would spot the distinctions, though they exist as I have briefly mapped out. Our primary job was reanimation, that these poems and stories felt alive and dynamic. We were not wishing to prop up the dead—no séance—rather dance with the living.

The work harassed our dreams, delighted us, challenged us, brought us yet closer. Neither of us realized these would be the last years of Tony’s life, but I can tell you that we were in delighted conversation about them up to several days before his death. And I tell you, I wept like they weep in these old stories on that day, the eve of my birthday.

I mentioned at the beginning that I come from a house where Jesus and Merlin rather banged around together, where Mary Magdalene may have thrown dice with Artemis. Tony and I noticed, again and again, that something in the beauteous spirit of the Celtic world both embraced Christ and kept the old gods tucked up under his wings. They are just too precious, too powerful to be sent to Heathrow with their metaphysical passports. No departure lounge for them.

I wanted to end this short selection with three short poems we worked on. The first for its elegant grief, the second for its adoration of nature, the third for its grit.

As I hope feels clear, these are not museum pieces. They are ardent, magical, woefully powerful pieces of work. These are things we have all lived though, and will continue to do so.

*

Lament for Reilly

Irish, traditional folk song

As I walked the strand one fine evening,

whom did I see but my fair-haired Reilly?

His cheeks were flushed and his brown hair all curly

and I felt that his death was galloping through me.

My God, Reilly, were you not the king’s son-in-law,

meant to be dressed in the finest gold cloth?

With bright white curtains around where you lay,

and a graceful lady combing your hair?

The shipwright who made the boat for your journey,

may his two hands crumble like old brown cork.

May the leaking plank in the hull of that boat

be burnt alive in a fire.

May the cold sea that surged through the hole in that plank

be jailed, found guilty, and hanged.

May the priest who prayed on the deck, and failed,

go to no heaven.

If I had been out that night with my nets all ready,

by God, Reilly, I would have saved you.

You looked so grand on your white horse last summer,

sounding your horn, your hounds by your side.

God made me alone so young; I hear them

repeating that Reilly is dead, my Reilly is dead again.

You should have heard their voices that night;

so excited to know there would be

not a wedding, but a wake;

and a brand new widow.

*

The Hermit’s Hut

Irish, author unknown, 10th century

I’m well hidden,

no one but God knows my hut;

enclosed by ash, hazel and heathery mounds.

Lintel of honeysuckle, doorposts of oak;

and the woods thick with nuts

for the fattening pigs.

My small hut on a path

smoothed by my own feet

is crowned by the song

of the blackbird in the gable.

It’s just a wee hut,

but it owns the whole forest;

will you go with me to see it?

From such a place

you can see red Roighne, noble Mucraimhe,

and majestic Maenmhagh,

and my view of the meadow is a green joy.

Water gushes from spring to my own happy cup,

the stags of Druim Rolach leap over my stream.

Swine and wild goats, and the badger’s plump brood.

All nature stays close

to such refreshment.

I make mead from this honey

and the good hazel-bush,

I make beer with scented herbs.

There is no quarrel here, no hour of strife.

Bright song of the swan, be with me always,

and the nimble wren in the hazel bough,

and swarms of bees, and wild geese.

The wind in the pines makes music sweeter

than any harpist.

I know where a patch of strawberries grows.

How could I not think

that God has sent these things to me?

*

The Yarrow Charm

Scottish-Gaelic, traditional folk charm

I kneel and pluck

the smooth yarrow

to spell-make,

to intrigue the stars to me.

Give elegance to my figure.

Subtract a little from the hips.

May my voice carry cheer,

like the yellowed sun,

may my lips be succulent, full and red,

like the juice of strawberries.

I shall be an island

in the blue-black waves,

a wooded hill on the land,

a sturdy ash staff when my heart is weak.

And just to be clear:

I shall wound every man,

but no man shall wound me.

__________________________________

From Cinderbiter by Martin Shaw and Tony Hoagland. Used with the permission of Graywolf Press. Copyright © 2020 by Martin Shaw.

Martin Shaw

Martin Shaw is a celebrated storyteller and mythologist, and the author of three books. He lives in Devonshire, UK.