On Black Millennials in Search of the New South

Reniqua Allen Tackles the Idea of the "Black Mecca"

Over the last few years I’ve been trying to find the “New South” that young Black millennials like me are moving to. That Black Mecca of upwardly mobile Black folk that is so prominent in the Black imagination. But I can’t. I look for it every time I visit the South. Instead of a feeling of freedom and comfort, all I feel is the weight of a past that doesn’t feel so distant. I want to love places like Charlotte, Charleston, Memphis, and of course Atlanta, the place the SNL writer Michael Che called the “Blackest” city in America, but it’s been hard. It’s been even harder after Trump became our president and I see Klan and Nazi rallies and White power signs peppering the region.

I feel guilty for my bewilderment because so many of my beloved friends and family adore the region. I love the gracious Southern hospitality, the grits, the sweet tea, the plethora of HBCUs, and the warm weather, but still, something about the South feels different to me. Perhaps it’s the pain when I see statues dedicated to the Confederacy, read about laws that won’t let transgender people use the bathroom (since 2013 over half of transgender victims of fatal violence lived in the South), hear about government officials actively fighting against memorials recognizing slavery, or ride past homes draped in Confederate flags. It’s painful and hurtful, and I don’t know how to react to the many markers of oppression, slavery, and Jim Crow that are on full display in so many areas of a sometimes unapologetic South. It feels anything but liberating or free. It’s as if the chains of bondage remain shackled to me, and I find freedom as stifling as the air in the Carolina heat.

It’s personal, too. In some ways, much of my identity is tied to the South. It is perhaps the painful memories often shared by my relatives that make me want to stay away. I always want to understand the stories better, but whenever I asked my now deceased great-aunt why she left Manning, South Carolina, during the Great Migration (after explaining to her what the Great Migration was and that she was a part of it) she said it was for better jobs, that there was nothing there for her to go back to. Recently, when I was afforded the opportunity to visit her hometown, I felt a sense of pride as I tried to find pieces of her South, overwhelmed when I learned that Brown v. Board of Education was started by a case in her county, and near tears when I found Meesha, a young educated millennial woman who may be my cousin. I was frustrated to learn of the vandalizing that occurred a few years ago at Meesha’s church, Bigger’s African Methodist Episcopal: someone kept removing the first letter of the name and replacing it with an N. And I felt saddened when I heard that two White men affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan burned a Black church down there—in 1995.

Because my grandmother and great-aunt did follow some sort of American Dream narrative and achieved those traditional monikers of success in the North (buying a home, getting married, owning their own businesses, putting their kid through college), their tales of the South stung even more. The North, most likely by sheer luck and also because of their hard work, was good to them. But in reality, it was also good to many of my relatives in the South who did not move North.

If you Google “the South sucks” you get plenty of material about rednecks, failing school systems, opioids, and Jesus, but that’s not my beef with the region. I’ve found that folks in the South are no less educated or “backwards” than people who live in my part of the country. In particular, the Black folk I know in the South are super educated. Most people I know have gone to college, bought homes, and are fairly happily raising their families. Meesha has two degrees and is the director of the county archives. And there is that sense of home. In the last presidential election season in particular, Black folk in states like North Carolina and Georgia played a significant role. Art, music, and other markers of American culture remain to flourish in the region.

For me, in such polarized times, when White privilege, nativist sentiment, and xenophobia have been clearly visible, the South, with its racial past and unwillingness by so many to renounce it, have especially frustrated me. When states like Mississippi refuse to remove the Confederate flag from their state flag or signs that urge to “Keep America White” are displayed so openly on the streets, I’m horrified in ways that I’m not up North. The public and bold way that Southern Whites cling to the flag and memorabilia is frightening, but it’s more than just the flag and statues. It’s about a history that so many in the region are unwilling to let go of, a past they seem to yearn for—an America of yesteryear. And while that sentiment has crept up nearly everywhere in the nation, the South always seems to lead the charge.

Yet no sooner had I proclaimed myself a Northern Yankee snob than I found a fairly recent report that confirmed my thoughts: the South is still dealing with race in ways other places aren’t.

There are signs of progress. South Carolina removed a Confederate flag after a racially motivated killing in a church in 2015 (and sentenced the killer to death). In New Orleans, a city I love, they have just removed the last monument dedicated to the Confederacy off of public property. A movement to take down additional monuments to the Confederacy has spread, despite the president’s lamentation of the trend. Nevertheless, the solid hold Donald Trump seems to have on the region makes me wonder if it really is a place that would welcome me.

Yet no sooner had I proclaimed myself a Northern Yankee snob than I found a fairly recent report that confirmed my thoughts: the South is still dealing with race in ways other places aren’t. The research came about in the aftermath of the Supreme Court ruling on Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, when chief Justice John Roberts blatantly asked, “Is it the government’s submission that the citizens in the South are more racist than citizens in the North?”

The lawyers in the case didn’t seem to want to deal with that question (the government’s lawyer replied, “It is not, and I do not know the answer to that, Your Honor”), but two law professors, Christopher Elmendorf of the University of California, Davis, and Douglas Spencer of the University of Connecticut, figured out the answer to that question. They proved that the South—specifically those states cited in the Voting Rights Act—correlated with research of non-Black residents who have “exceptionally negative stereotypes” of Black people. Plain and simple, it seemed: the study confirmed that people in the South do seem to have more anti-Black prejudice than other regions of the country. Other reports I read contradicted that a bit, with one specifically noting that the research about whether the South was more “racist” has been inconclusive.

I was left trying to figure out if the South was really that great for Black millennials and whether upward mobility—economical, spiritual, cultural, or all of the above—looked different in this region. I began to question my generalizations and simplistic understandings of an entire geographic area and decided to reach out to Jessica Barron, a sociologist and demographer. She thinks that race and racism play out in different ways historically and contemporarily in the South. She noted that the South’s particularly harsh regulation of and brutality toward Black bodies was horrific, but doesn’t discount policies like redlining that also damaged Black communities in Northern cities like Chicago. She explained, “The South is an easy scapegoat. After the Civil Rights Movement, when the country wanted to rewrite the narrative of this color-blind racial utopia, somebody has to be the villain. Somebody has to be the antagonist.”

*

For a while I wondered if the South, and particularly Atlanta, was a good metaphor for the upwardly mobile Black experience. Popular culture has certainly hyped up the South as the place to be for upwardly mobile Black folk with television shows like Donald Glover’s award-winning Atlanta, a range of Tyler Perry films, and Beyoncé’s stunning visual project Lemonade firmly rooted there. Recently, many Black coming-of-age stories seem to be set away from New York City, while it still remains the place for several White coming-of-age stories like Girls and Broad City. Even mainstream media outlets have picked up on the trend. Forbes said the South had become in many ways “the new promised land” for Blacks. The New York Times called Atlanta the epicenter of the Black “glitterati.”

I couldn’t help thinking about the other side of the South, especially that more working-class Atlanta that Glover portrays in his popular series. Was that too the promised land? In 2013, the Brookings Institute released a report that found that the city’s wealthiest residents had twenty times more than the poorest that year, and a few years later, the Federal Reserve chief of Atlanta noted the city was “one of the worst” in terms of economic mobility. Of course this disproportionately affects the city’s Black residents, and the gap between White and Black households is high. In 2016, the median income for White families in the Atlanta metro area was $78,000 a year, compared to $50,000 for Black households. And a report by Clark Atlanta University professors in 2010 also found Blacks were unemployed at twice the rates of their White counterparts (reflecting a longstanding national trend), that there were fewer supermarkets in Black neighborhoods and less access to public transportation in these same communities. For all its positives, the idea of a “Black Mecca,” it concluded, was more “public relations and image management” than reality.

There are some other statistics to consider when looking at the South as a region. While Black millennials who live in the South have the highest rates of employment in the country, at 68.9 percent, they also earn the lowest (making about $22,000 in median wages) and have the lowest levels of educational attainment of millennials in other parts of the country.

I still want to believe in America.

I don’t know what to make of Atlanta and many of the other parts of the South. The data seems to show that the realities of Black life there, like other parts of the country, can be tough and it certainly appears to be no utopia or promised land for Black folk. But there still seems to be something to this idea of the city as a Black Mecca, which people hold near and dear to their heart. It seems to be something not always solely measurable by the usual markers of success and economic well-being, but by happiness and work-life balance.

I feel so betrayed by America, by those on the right, by White women, that maybe it doesn’t even matter where I live. I still want to believe in America. Believe that things can be better. America of late is making it hard. Perhaps the South is this place of my American Dream, even in a land where the hope of 2008 seems elusive and change a joke. Perhaps getting out of blue-state liberal land, which is never quite as ocean blue as I dream of, is the answer to me finding that slippery American Dream. Perhaps it is my future.

Jessica Barron, the sociologist, reminded me of the importance of a visible humanity that often draws young people to the South. It’s slower, less competitive, and more communal pace can often feel like a needed respite for a generation that’s tired of working twice as hard in their personal and professional lives. “People want to move away from this grind and this constantly trying to vouch for your humanity and dignity,” she said. Black people can go to a place where Blackness is seen as valuable because of the large Black population and is held to some kind of standard, even if it does have roots in slavery. “This is still a place that is somewhere that I want to be because I will be seen as Jessica XYZ versus the Black girl here doing XYZ. I think people underestimate that.”

After our conversation, I began to see the South in a different light, as a mystical, mythical, complicated mess of pain and beauty. Maybe the Black millennials who choose to live there have it right.

In the spring of 2017, I stood in the sticky hot heat watching the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in New Orleans. As workers, allegedly clad in bulletproof vests, chiseled loudly away at the over-hundred-year-old statue, I couldn’t help but feel that progress was being made despite the previous night’s protest over the removal. In that moment I ignored the few Confederate flags in the crowd. I was overjoyed to be part of a diverse group of people watching Lee be evicted from his perch over the city, waiting anxiously to erase a blighted history. I was pleased when two Black men gave out some Powerade to the crowd. It was a comforting moment, and I thought, despite whatever mess was going on in Washington, maybe change could happen.

But then some folks came up arguing about how the statue deserved to stay, which somehow devolved into a conversation about “those people” who apparently get “plenty,” and once again, I was disappointed in the region. As the statue popped off the structure, secured only by cords and rope, it looked ironically as if a lynching was occurring.

The next day I headed to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, to visit a church created for LGBTQ members, where I was greeted by a tattoo-covered, nose-ring-wearing lesbian minister, and once again I noticed the emergence of a different (yet still complicated) South.

__________________________________

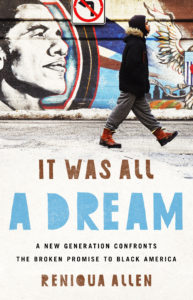

From It Was All a Dream: A New Generation Confronts the Broken Promise to Black America. Used with permission of Bold Type Books. Copyright © 2019 by Reniqua Allen.

Reniqua Allen

Reniqua Allen is an Eisner Fellow at the Nation Institute and a former fellow at New America and Demos. She has written for the New York Times, Washington Post, Guardian, Teen Vogue, and more, and has produced for WNYC, PBS, and MSNBC. Allen lives in the Bronx.