On Bill Buckner's Greatest Catch (with a Little Help from Larry David)

Abby Ellin on the Rehabilitation of a Goat

The savior of my youth, the man who restored dignity to a hapless ball player—and thousands of despondent fans in the process—is not John Henry, Theo Epstein, Alex Cora, or any of the men responsible for finally bringing a World Series title to my beloved Red Sox. It’s not even someone with a sports background. No, the person who redeemed a beleaguered first baseman is a neurotic, balding germaphobe named David.

Larry David.

Yes. That Larry David. The misanthropic mastermind behind Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and SNL’s version of Bernie Sanders; the astute observer about the world we inhabit. (A typical Larryism: “What is this compulsion to have people over at your house and serve them food and talk to them?”)

To fully comprehend my gratitude to L.D., you have to understand my history with the Red Sox, which dates back to the 1975 World Series: the Sox versus the Cincinnati Reds.

It was October, and I was sitting in the bleachers at Fenway Park with Danny Schiff, flirting like the eight‑year‑olds we were. Real flirting. True flirting. The most honest flirting there is. I’d gotten braces earlier that day and kept running my tongue over the metal. It felt strange to me, but I wasn’t embarrassed. I grinned widely any time Danny glanced at me, my braces gleaming in the floodlights. It didn’t occur to me to be embarrassed. I was cocksure and defiant, and exactly where I wanted to be: surrounded by my boys on a cool autumn night. With neither of our parents in sight.

And they were my boys, those 70s’ ball players: Rick Burleson and Carlton “Pudge” Fisk and Dewey Evans and Jim Rice and Fred Lynn and Carl Yastrzemski. Yaz! For some inexplicable reason, my third‑grade teacher brought in a plastic swimming pool and liberated a pack of crayfish into the water. We students got to pick one as a pet and name it. Mine, the biggest, was called Yaz. Crayfish make lousy pets, but Yaz was cool, with a splotch of pink nail polish on his shell, so we could identify him in a lineup.

The confident girl of eight had been replaced by an angsty and angry eighteen‑year‑old.

But my real hero was Luis Tiant Jr., the great Cuban pitcher. (I would have named my crayfish for him, but Danny Schiff beat me to it.) One afternoon Tiant showed up outside the school gym with an older man who looked just like him. It was his father, Luis Senior. A bunch of us surrounded them and Tiant signed the slips of paper we handed him. But as my own father pointed out later on, it was Luis Senior who was the real star. He had also been a pitcher, but he wasn’t allowed to play in the Major League Baseball organization because of his skin color. This was the first I’d heard about that, and it hurt my stomach.

The Sox lost the Series in seven games, and at the end of fourth grade Danny and his family moved to Houston. I never heard from him again, and the Sox never gave us much reason to celebrate. For the remainder of my childhood, the Red Sox never made it into another World Series.

Then, 1986.

That year, I was a sophomore at a small college in upstate New York. It was cold and bleak and I didn’t want to be there. What I really wanted to do was take a year off after high school to find myself (or, ideally, someone else), but my parents squashed that idea like a pesky crustacean.

The confident girl of eight had been replaced by an angsty and angry eighteen‑year‑old. I couldn’t connect with my peers for many reasons, not least of which that they were Yankee and Mets fans. I was miserable and lonely.

And yet . . . something good did happen: eleven years after my night in the bleachers with Danny Schiff, the Red Sox were headed back to the World Series.

I didn’t want to watch the games with these misguided New Yorkers; I wanted to be in Boston with my people. But I latched onto a handful of New Englanders also stuck behind enemy lines. By Game 6, we were feeling pretty good.

It was as if we’d watched a suicide in real time—which, in effect, we had.

It didn’t last. Oh, boy did it not last. Like all of America, we witnessed one of baseball’s Greatest Tragedies, involving a ground ball, first base, and feet spread a little too far apart. As the ball rolled through the first baseman’s legs—his name was Bill Buckner—everyone around me yelped as if they’d smacked headfirst into the Green Monster. My own feelings ranged from rage to pity to despair. It was as if we’d watched a suicide in real time—which, in effect, we had. For the next few days the campus was littered with conversations about Buckner’s error: in classes, at meals, in the dorms. No one could shut up about it.

I needed to flee.

So when a guy I barely knew asked me if I wanted to road‑trip to New York City in his brand‑new BMW, I jumped. He said something about a ticker‑tape parade, but I had no idea what that really was. Why would I? My team had never been given one, at least not in my lifetime. It sounded like fun: A parade! With confetti! I didn’t realize that this wasn’t like Times Square on New Year’s Eve, when everyone celebrated in unison around a shared event. This was something for a very specific audience—one I was emphatically not a part of. Of course, I wouldn’t know this until we grabbed the 1 train to lower Manhattan, smushed between 64.8 tons of falling orange and blue paper and people celebrating—nay, reveling—in the catastrophe that befell my Red Sox.

“Orosco!” the fans hooted. “Ohh‑RAWWWW—sco!”

I stood there, my teeth clenched, my lips pressed into a hostile line. “Boo!” I yelled. “Boo!”

Everyone turned to me, eyes blazing at the traitor in their midst. I was lucky to make it out alive.

*

The Red Sox eventually broke the Curse in 2004 and 2007 and 2013 and 2018. But thirty‑three years after the Gaffe Seen Round the World, Buckner was still greeted with derision. His name was both a euphemism and a verb, and not a happy one like, say, “to kiss.”

Then episode 9, season 8, of Curb Your Enthusiasm came along. The “Mister Softee” episode, 2011. And everything changed.

*

Because it is Larry David, everything is always convoluted and weird, but this episode is especially so. It involves a softball game in Central Park, and a ball rolling through the first baseman’s legs—Larry David’s legs. It’s not his fault, not really: he’s distracted by the Mister Softee jingle emanating from an ice cream truck whizzing past, and it catapults him back to his own childhood. Back then, poor Larry, his Jewfro at full mast, is on the losing side of a strip poker game played inside of an ice cream truck. Fifty years later, he’s still traumatized by the relentless music. He can’t be held accountable for his error.

Everywhere they go—even on the streets of Manhattan—people taunt them.

The team owner is apoplectic. “YOU BUCKNERED IT!” he screams. “You fucking Bucknered it!”

Larry shrugs. Shit happens.

A few hours later, Larry attends a sports paraphernalia event to buy a gift for his manager, Jeff Greene: a baseball autographed by Mookie Wilson, the Met who lobbed the ball that Buckner missed.

Buckner is also at the event. He and Larry start talking and decide to have lunch. Everywhere they go—even on the streets of Manhattan—people taunt them.

“Fuck you, Buckner! You stink!”

“Don’t let the door go through your legs on the way out, Buckner!”

Larry brings Buckner over to Jeff’s apartment, so he can give him the signed baseball.

As Buckner stands at the open window and admires the view, Larry tosses him the ball. Buckner misses and it flies outside.

“I thought you were a baseball player!” Jeff’s wife, Susie, shrieks. “You can’t catch a goddamn toss?”

“Shit happens,” Buckner says, shrugging.

Later that day, Larry happens upon a burning apartment building. A woman and her baby are trapped on a top floor. The firefighters set up a rubber tarp, and the woman is supposed to chuck her baby out the window.

She takes a deep breath and flings her child into the ether. He falls, in slow motion, onto the rubber. But instead of landing, he bounces again, soaring high, high into the air. Coincidentally, Buckner is staying at a hotel around the corner, and he strolls by this seismic event. He leaps into action, arms outstretched, lurching toward the baby. Terror is etched onto everyone’s faces; they knew who this man is. He can’t catch a ball for shit, let alone a kid.

It’s the World Series and the ticker‑tape parade rolled into one. Buckner is hoisted onto someone’s shoulders, brandished as if he’s the Commissioner’s Trophy.

But then, hallelujah! Buckner flies into the air, arms outstretched, and catches the bouncing child. Buckner stumbles onto the ground but he clutches that baby to his breast, smiling broadly. The crowd—a New York crowd—roars! It’s the World Series and the ticker‑tape parade rolled into one. Buckner is hoisted onto someone’s shoulders, brandished as if he’s the Commissioner’s Trophy.

Buckens beams. He finally gets the reception that should have been his thirty‑three years ago.

I weep.

*

I weep again, seven years later, when my Twitter feed blows up: Bill Buckner has died. The pundits and columnists once again dissect the series; in retrospect, maybe Buckner wasn’t so bad, kinda like Nixon. After all, the Sox wouldn’t have even made it to the World Series without his help. The dude had a stellar record.

It’s a nice sentiment, but a little too late. Buckner doesn’t need it anymore. He was redeemed in the most brilliant way possible.

__________________________________

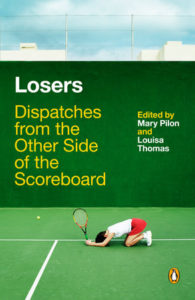

From Losers by Abby Ellin, edited by Mary Pilon and Louisa Thomas, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Mary Pilon and Louisa Thomas.

Abby Ellin

Abby Ellin has been contributing to The New York Times since the late 1990s. For five years she wrote the “Preludes” column in the Sunday Money and Business section and has written about everything from failed Lasik surgery to the Ms. Senior America pageant to a man who faked cancer. She is the author of Duped: Double Lives, False Identities and the Con Man I Almost Married.