On Being the Oldest Guy at Skate Camp

Cheston Knapp Tries to Fit in at the "Funnest" Place on Earth

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here? Where should we be today?

–Elizabeth Bishop

Orientation. It’s Sunday, June 16, 2013—Father’s Day and the first of Windells’s Summer Session 2. Late afternoon and the sun’s out and the sky’s a kid’s picture of the sky, with great big cotton-ball clouds seemingly glued to a lucid blue. I’m sitting with the other skateboarders along the coping of a drained pool in the Concrete Jungle part of campus, which is tucked in the woods off Highway 26 in Welches, Oregon. My board is in my lap and my helmet’s beside me and I’m wearing my favorite of the new T-shirts I bought for camp. It says RESEARCH across the chest. My legs are dangling beneath me with that pleasant sense of groundlessness I loved as a boy, perched in too–high chairs, and didn’t know I missed. Until recently, I hadn’t realized that it was possible for one’s body to miss something that one’s mind didn’t also miss. That one’s mind wasn’t even actively aware of.

After a brief camp-wide introduction in B.O.B., a hangar that houses the indoor skate park, the trampolines, and the pit of foam blocks, we were split off from the snowboarders and skiers for our sport-specific briefing. The facts here are simple enough: a month back I signed up to attend Windells’s Adult Skateboard Camp. I paid online—a thousand bucks for the week seemed a steal at the time—and emailed over the 20-page packet of waivers and my insurance information, as well as a physical form my doctor had to fill out. But like so much about my life these days, knowing these facts doesn’t diminish a certain shimmery unreal quality that clings to them, and I almost feel like I need proof that I’m really here. The best I can find is the neon-yellow wristband I’m wearing, its adhesive so strong that it’ll likely depilate my forearm for days to come. This takes me back about an hour, to when I checked in and learned, among other things, that to remove the wristband would bar me from all camp-related activities, including meals and the dodgeball tournament. The wristband is a small but comforting reminder that I’m really there—I’ll take absolutely anything I can get in the way of continuity. Feeling lately’s been that whatever ligatures were used to knit me together have stretched thin, if not snapped entirely.

Because I was going it alone, one of my unstated goals entering the week was to make a friend, a buddy. Best-case scenario, to get a nickname. I’d read about the Adult House’s hot tub and had imagined having a soak and swapping stories with my fellow campers, slightly embellished tales of how we’d slain our local spots growing up, shredded ledges and conquered sets of stairs. I’m perhaps a skosh overeager to make this happen, which must be why I venture, to no one in particular, that we’ve all gathered here to get our “bearings.” When no one laughs, I spin one of the wheels on my board in a schmucky hint-hint but don’t even get a sympathetic titter. And for a moment I worry that I’ve inadvertently marked myself as a poser, what with my new T-shirt that still has its fold creases and my newish board and my shoes that are hardly scuffed and my lickspittling joke. I stop short of acknowledging the truth: that that’s exactly what I am, and in ways far deeper than I’m willing to admit.

Jamie Weller, the head coach-counselor, starts to call roll. He’s mid to late thirties and his hair is close-cropped and so blond I can’t tell whether he’s maybe balding a little. He’s short and stocky and looks a little like someone you’d encounter in a mosh pit. In response to their names, each camper raises a hand and says, “Here.” As I watch on, a notion begins to take shape out on the edge of my mind. Most of the campers’ faces are in varying stages of development, with disproportionate noses and ears and skin stretched like Silly Putty over still-growing bones. Their limbs are Muppet gangly and their feet almost clownishly oversize. There’s also a coterie of prepubertal boys sitting together, a feral-looking crew that makes me nervous, they seem so unpredictable. After his name is called, one of these kids says, “Present,” and all the boys around him laugh and dole out congratulatory dunches. I bristle inwardly at this rival jokester and fear that if things continue apace, I’m in for a long week, buddy-wise.

“For a moment I worry that I’ve inadvertently marked myself as a poser, what with my new T-shirt that still has its fold creases and my newish board and my shoes that are hardly scuffed and my lickspittling joke.”

My mind wanders off in defeat. I work my wristband around and my arm hair prickles with pleasure-pain. Ever since I got married, I’ve fussed with my wedding ring in much the same way, mystified by its presence on my finger, wondering, at times, what it could possibly signify. I’ll celebrate my two-year anniversary in a month and I’m still not a hundred percent on what it means to be a husband—that word seems to define a state of affairs that I haven’t fully grasped as part of my identity. I focus on the pool. Although it is drained, it was never intended to hold water, and I’m having a little Wittgensteinian moment with that one when I hear my name.

“Here,” I answer automatically, but it comes out sounding more like a question. The campers look at me like, finally, the solution to this riddle.

“Great. All right,” Jamie says, and nods encouragingly. He checks his list. It seems mine is the last name on it. “There’ll be another one of you, too. Maureen. She’s on her way, just not here yet.”

“Cool, thanks,” I say.

The notion is fully articulable now: I am thus far the only adult to show up to Session 2’s Adult Skateboard Camp. I am 31 years old and some fast math tells me I’m technically old enough to be every other skate camper’s dad. It is then that I recognize the buffer of space they’ve left around me. There could be no congratulatory dunches for me after one of my jokes because I couldn’t touch the closest person on either side of me if I leaned over.

I put it together that there’s been a miscommunication here. When I spoke with a camp representative last week, I asked how many other adults would be in attendance at Session 2. I was told there would be eight, a not unreasonable number. Enough folks to fill a hot tub. But what I didn’t know to ask was how many of those eight would be skateboarding, not skiing or snowboarding. Had I, I would’ve learned only one. Some lady named Maureen.

“Okay,” Jamie says, and turns to address the lot of us. “So who here loves skateboarding?!”

Everyone hoots and cheers. The campers standing poolside take their boards by the tails and knock the noses against the coping. One kid makes this whooping noise that probably qualifies as ululating.

“Nice!” Jamie says. “I can already tell this group’s gonna be tons of fun.” He then invites the four other coach-counselors to introduce themselves. They’re all early twenties and stand with the same languorous cool-guy posture that skaters stood with back when I was growing up. After we go over the rules and the schedule, Jamie hints at the shindig that will end the week. In B.O.B. there will be tunes and dancing and skating and salty snacks and candy and soda and contests and raffles for free boards and other righteous gear. They’ve christened this sober bacchanal “Disorientation.”

“This is your week,” Jamie concludes. “You’re in charge of how much fun you have.”

There’s still some time before I have to meet with the other adult campers and I need to unpack and do my Father’s Day duty and call Dad, so I ride back toward the Adult House, a four-bedroom rancher across the five lanes of Highway 26, quarantined from all the other bunks.

Campus is an amoebic network of concrete ramps (bowls and quarter pipes and spines), manual pads, and stairs that have low rails and ledges—89,500 square feet of skateable terrain. Behind the dining hall there’s a course for BMX bikes, big dirt jumps that lead to other big dirt jumps; I swear that if I listen really hard while looking at it I can hear the midi soundtrack to Nintendo’s California Games. For the skiers and snowboarders, there are two sets of dry slopes, which are made of small interlocking sections of white plastic that have firm cilia protruding from them—up close, they look like reefs of sea anemones. In the woods there’s a steep approach to two ramps from which campers may launch and land in a great inflatable bag like the water blobs you find on lakes, and in front of B.O.B. is the Ranch, a gentle declivity about a hundred yards long, dotted with jibs for campers to develop and refine their Slopestyle know-how. The way these areas sit in amid the pine and fir trees gives the few acres a distinct Fern Gully meets Neverland feel. And I understand it’s all something of a wet dream for my fifteen-year-old self, with whom I’ve been in uneasy touch of late.

I make it to the highway and stand by the entrance to the camp. Cars whiz by in either direction. As I wait for my chance to Frogger across the five lanes, I regard the camp’s sign and its curious punctuation. WINDELLS, it reads, after the founder, Tim Windell. And below, in big block letters, THE “FUNNEST” PLACE ON EARTH.

__________________________________

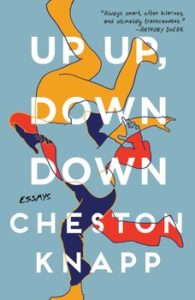

From the essay “Something’s Gotta Stick” in Up Up, Down Down. Used with permission of Scribner. Copyright © 2018 by Cheston Knapp.

Cheston Knapp

Cheston Knapp is the managing editor of Tin House. He lives with his family in Portland, Oregon. Up Up, Down Down is his first book.