On Bafflement: Reflections on Marilynne Robinson and the Theology of Skateboarding

Kyle Beachy Digs Into the Mysteries of Existence

When we perceive the obvious from even the slightest of skews, we see that it is, in fact, issuing a request. For? Generosity is one way to put it. Radical openness is another. A sort of simmering faith in both the object of our perception and also our capacity to perceive it in new ways.

The process I’m describing is a kind of return to that obvious thing still in our midst. A second and third and often many more attempts to resee and reconceptualize a thing driven by a faith that the qualities that made the thing obvious might still serve some purpose, might still yield new meaning. The philosopher Richard Kearney has formulated a term, anatheism, which in its prefix (ana-) signals “a critical hermeneutic retrieval” of that which has come and gone, a return to the old thing for new guidance toward understanding the world. Kearney’s formulation is exemplified, he says, in the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins’s description of the creative activity: “Aftering, seconding, over and overing.” And so, a retrieval and revisitation by way of repetition: an over and overing practiced in a way, says Kearney, that is repeated “forward, not backward. It is not about regressing nostalgically to some prelapsarian past.” In Kearney’s case, the thing being retrieved is God after Nietzsche’s declaration that God is dead.

In our case, that thing is skateboarding after it has been corporatized and commodified and drained of all subversion, reduced to athletic spectacle. Skateboarding’s theology has been composed in magazine and video texts that have, for decades now, remained faithful to the forms that have come before them. A decade of looking newly has begun to yield new objects and understandings. By our own over and overing we can, I believe, formulate a conception of skateboarding’s sacred obviousness, its everyday quiddities, that will escape the cosmic gravity of nostalgia and mythology and perhaps propel it into a new orbit.

And so, by unfolding the obvious, by spinning it in our palm and staring deep into its core, we see that its resistance to our gaze is a type of bafflement. And to be baffled is something rather else than to be confused. As it emerged in the late 16th century onward, to baffle meant to disgrace, foil, and hoodwink; in short, to cheat. Over time, the word shifted into a usage less specific to the criminal, a more general action of bewildering or confounding. It has always carried an air of defeat and confrontation, which has calcified into its most current meaning: to frustrate or foil. Which means also an air of victory, if you can hear it that way.

The word confuse comes into common speech around this same time, also as a transitive verb. But during the 19th century its dominant use changes to something more like to mix, to make disorder where once had been order. And from this meaning it acquires a use as a common noun, confusion, an everyday state we can speak of today without creating the least conversational friction. To be confused is to be befuddled. To be confused is, in a sense, to be alive in the third decade of this 21st century.

To be baffled is something rather more extreme and less spoken of. It requires a greater humility, perhaps, to admit defeat in this way. Or perhaps greater pride to think one’s personal challenge is worthy of such an old, archaic set of letters. What’s more, bafflement hides in other terms. Like, do you see it there at the end of Joan Didion’s most famous paragraph, to open “The White Album”? It is what remains when the stories we tell ourselves in order to live begin to crumble. Bafflement is the failure to establish the “imposition of a narrative.” Bafflement by another name is Didion’s “shifting phantasmagoria,” all of that chaos and disorder, the primary mysteries of existence.

To traffic in the baffling is to maintain a certain endurance for that which doesn’t yield much, maybe any, result.Or, even better, it is there in Marilynne Robinson’s majestic and perfect Housekeeping, a slim, slow novel that appeared in 1980. Her narrator is an adult Ruth, recalling not only her own childhood, but her family’s history back through generations, trying to riddle what would make her mother leave her and her sister, Lucille, on their grandmother’s porch before driving her car off of a cliff and into the town lake. There is, of course, no question less answerable than, “What would make someone take their life?” And yet, here we are every single time it happens, peddling our meager theories.

So there’s bafflement in the framing of Robinson’s plot, and even more so in the craft of her story, its form and style. What at first reads as a standard first-person reflection is, upon a better read, revealed to be a kind of subjective omniscience. Her sentences, long and subordinating, define Housekeeping’s world by a meticulous, polished ordering of relations. Ruth’s is a syntax of total control, which leads, due to necessary ignorance of much of what she’s describing, to frequent hybrids of certainty and doubt. She’ll tell us how “it must have seemed,” to a character, or “would have felt.” And always reminding us, “I think.” But the lake’s depths cannot be charted. Bafflement has prevailed, and Ruth is left with only myths and her imagination. “Say” that this happened, she insists at the novel’s climax, bobbing in a small rowboat upon the selfsame lake that swallowed her mother. “Say” that this were the case, she pleads, sorrow surfacing for the story’s first time.

As a character, Ruth is what we might call flat. Also, static. The grand totality of her desires center on comprehending her mother’s incomprehensible choice. But with Ruth it is not a matter of what but rather how. Over and over again, she collides with bafflement, and in the end, this longing that is her narrative folly—the suicide’s hard epistemic limit—gives form to the novel we’re holding. Her quest takes the form of memories real mixed with memories imagined, and they deliver her only to where she is at the story’s beginning, baffled. Beginning storytellers learn that desires and obstacles create plot. Ruth has no desires, only needs.

But a true need, understands Ruth, “can blossom into all the compensations it requires.” Plots, at their best, confuse just long enough to provide surprise by their ends. Or if not surprise, at least a frisson of completion, the spark of the circuit closing. Existence, meanwhile, baffles. Let me go further: any story that provides answers is a lie. “Though we dream and hardly know it,” says Ruth, “longing, like an angel, fosters us, smooths our hair, and brings us wild strawberries.”

To traffic in the baffling is to maintain a certain endurance for that which doesn’t yield much, maybe any, result. It is in this sense a sort of gluttony, or masochism, or at the very least a strange appreciation indeed. On a sunny afternoon, instead of riding my skateboard, I sit with my wife and dog and stare into my Swiss-made ball bearings that are soaking in a shallow dish of brake cleaner. I watch little particulates of grime swirl in the fluid, which is toxic. Mankind went 1,400 years believing a Ptolemaic astronomy of spheres that located the earth at the center of the universe. I am only speaking of wood and metal and plastic and grease, bits of silicon carbide glued onto paper that adheres to the top of a board. Say, though, that it is more. I think it must also be more.

__________________________________

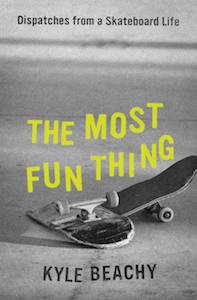

Excerpted from the book The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches from a Skateboard Life by Kyle Beachy. Copyright © 2021 by Kyle Beachy. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.