On Babar: Model of Integration or Crumbling Myth?

French-Algerian Author Faïza Guène Considers Her Relationship to the Iconic Elephant

How can we not see in Babar, the crowned hero of my childhood, a symbol of integration, Frenchstyle?

For a long time, I looked upon this paternal and kindly protagonist with a mixture of innocence and naivety. He probably reminded me of my own father, a sturdy former builder with huge fists and a voice both deep and reassuring.

I read Babar as a child does, artlessly.

While writing my novel Un homme, ça ne pleure pas (Men Don’t Cry), published in France in 2014, I became particularly interested in what we pass on from one generation to another, in the colonial legacy and in identity complexes. So I decided to explore the challenges of assimilation through a female character, Dounia, who severs relations with her family, frees herself from tradition, rejects her Algerian identity and becomes the darling of the white Parisian élite, to the dismay of her parents who deem her to have traded them in for the Republic.

My idea was to follow the divergent journeys of the three siblings whose family is at the heart of my novel. Must we renounce our nearest and dearest in order to be free? Do we have to conform in order to be accepted? What about our heritage?

I have been working on such questions around identity, central to all my writing, for more than a decade. To illustrate the “betrayal” reserved for assimilated persons—and which I consider as a form of injustice—I have chosen the figure of Babar.

If I use the word “betrayal,” and it is certainly a strong word, I do so not because I wish to provoke but rather to articulate the feeling of disillusionment that might arise following an otherwise “exemplary” career; when, in order to succeed, you have confronted social derision, condescending attitudes, racism and rejection, when you have had to fight for your place, only to discover on making it there that you are still not considered un bon français (a good French citizen). You are left sensing that you must have taken a wrong turn, that you were deceived, manipulated.

Are such happily assimilated characters a model of integration or a crumbling myth?

For a novelist born in France and the daughter of colonized Algerians, this provides extremely rich subject matter. I needed a powerful image if I wished to examine a concept of this complexity. Babar the Elephant was the perfect embodiment: a household name and one that would enable me to make connections with a topic for our times. It occurred to me that, through Babar, I could tackle a social issue key to understanding France today, by exploring simply, metaphorically and with a light touch the challenges and disappointments faced by an assimilated character. Who are these Babars? Are such happily assimilated characters a model of integration or a crumbling myth?

The title for this chapter in my novel is “Babar Syndrome.” One of the characters, the younger sister in the family, sees Babar as a metaphor for the French colonial empire and its fallout, viewed through the prism of an assimilated character.

In the case of Babar, once he has been educated by the elderly white lady—once he has been “civilized” by her, in other words—he teaches this new lifestyle to the rest of the elephants: the “best” way to live and to conduct oneself. Let’s interrogate the very essence of this journey, the notorious civilizing mission. Babar isn’t accepted among humans as he is, meaning in and of his nature.

How can we not reflect on those men and women of color who have all but repudiated their identity, part of their history or their religion, some of whom have changed the family name on their birth certificate so as to conform in the nth degree to what is expected of them, in the belief that they are meeting some higher requirement and will become an integral part of society? Often, they achieve prestigious careers. Sometimes, they overlook who they are, they adopt a form of contempt for their class, their family, and suffer from dreadful complexes. They cut their ties, renounce their own. Which only goes to show the extent to which they have earned their place. Likewise, Babar undergoes a meticulous apprenticeship in order to rub out those funny elephant habits.

And so, although his mother was killed by a hunter, it is amongst men and in the city that Babar will find refuge and receive his bourgeois apprenticeship.

How can we not reflect on these children of former colonies, born on French soil, supposedly French de facto, who adopt a French lifestyle so as to be accepted, to meet with approval, as if they had never truly left behind their state of being colonized? Deep down, they want to do the same as everyone else, even if they often do more than everyone else. They are encouraged along the way, until the day when, in all likelihood, they will hit the glass ceiling and be cruelly reminded that you can’t erase what you are.

An elephant on two legs, who lives the life of a grand bourgeois, evokes in my mind those assimilated persons who become complicit and who exist in a state of denial, refusing to see the prevailing racism and paternalism. Babars who, by dint of walking on two legs, wearing threepiece suits, driving a car and reading books, forget they are elephants.

Babar stares at himself in the mirror and sees a man. Until the day when he is cruelly reminded that the reality is a whole other story.

Once an elephant, always an elephant, at least in the eyes of others.

But in the eyes of a child, the child I used to be, in the eyes of all the young readers of The Story of Babar: the Little Elephant, and beyond those metaphorical aspects of post colonial society, Babar is an animal who longs for peace. He fosters dialogue between two worlds, between two civilizations.

Babar is the gobetween who, for me, also embodies the cross-class figure: he is the first from his background to succeed in bridging the gap. He represents the possibility of understanding and mutual respect. He doesn’t merely adapt himself to the human society he is joining but rather takes the best from both ways of life in order to create a kind of ideal world.

It is his innocence that allows him to do so, and that is what I will hold on to in Babar.

__________________________________

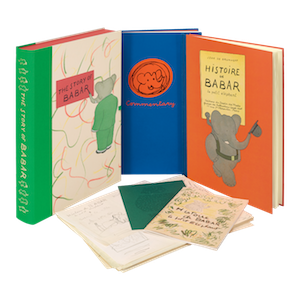

Excerpted from The Story of Babar. Used with the permission of the publisher, The Folio Society. Copyright © 2021 by Faїza Guène. Translated by Sarah Ardizzone.

Faїza Guène and Sarah Ardizzone

Faïza Guène is a French writer and director. She was born in France in 1985 to parents of Algerian origin. Spotted at a writing workshop at the age of 18, Faïza made an astonishing literary debut with the international bestseller, Kiffe kiffe demain (Hachette Littératures, 2004), which has been translated into over thirty languages. This was followed by five further novels Du rêve pour les oufs (Hachette Littératures, 2006), Les gens du Balto (Hachette Littératures, 2008), Un homme, ça ne pleure pas (Fayard, 2014), Millénium Blues (Fayard, 2018) and La discretion (Plon, 2020). Faïza has acquired a reputation as one of France’s most unique contemporary literary voices. She also writes for film and TV, and is currently one of the principal writers on Disney Europe’s series Oussekine.

Sarah Ardizzone is a translator from the French-speaking world with some fifty titles to her name. Her work spans picture books, graphic novels and travel memoirs as well as children’s, young adult and literary fiction. Notable authors include Alexandre Dumas (a fresh version of The Nutcracker), Faïza Guène, the outspoken young French Algerian voice from the banlieue, and former ‘dunce’ Daniel Pennac, whose autobiographical polemics about education are illustrated by Quentin Blake. Twice recipient of the Marsh award, she has won the Scott-Moncrieff prize and a New York Times notable book accolade.