On Authenticity, Research, and Writing From the Diaspora

V.V. Ganeshananthan on Writing About Sri Lanka

As a person of Ilankai (Lankan) Tamil heritage who grew up in the United States, I write from a diasporic position. I set my first novel, Love Marriage (Random House, 2008), primarily in the diaspora, without imagining an ending to the Sri Lankan civil war. Yet during the year or so that I traveled and spoke to readers in support of that novel’s publication, Sri Lankan security forces defeated the militant separatist Tamil Tigers.

As a quarter-century of fighting drew to a grim close, I encountered this impossible reality and the failure of my own imagination everywhere, perhaps most often in the form of other people of Ilankai Tamil descent who were, like me, thinking of the unknown number of Tamil civilians trapped between the security forces and the Tigers.

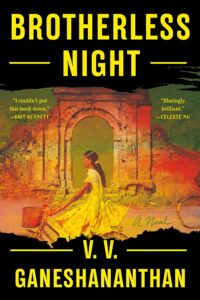

My second novel, Brotherless Night, a novel set primarily in Sri Lanka itself, is an attempt to contend with the war’s end by returning to its beginning.

This means that I chose a time I could have lived through, but did not. Some, of course, argue that a diasporic position is inherently inauthentic. You should stay in your lane. But history lays the road of a diasporic person wide and far. My lane winds across oceans. Who is policing my route? Who is one person to declare another authentic, and what is the motive of a person who wishes to run me off the road? Many diasporas are, of course, formed when people seek refuge. To deny diasporas their voices is, in some regard, to practice the politics that drove them to do that in the first place.

Many diasporas are, of course, formed when people seek refuge. To deny diasporas their voices is, in some regard, to practice the politics that drove them to do that in the first place.

This is dangerous given how many diasporas are made of persecuted minorities, and how Americans in particular read global histories through a lens of American exceptionalism. As some people acknowledge hierarchies of grief, others consider hierarchies of authenticity. But Americans—particularly those from dominant communities—are often not very good readers of hierarchies of authenticity, believing them to be simpler than they are.

Countries shrink to one location or heritage, and a novel based in Colombo is discussed as though that experience can be exchanged for one in Jaffna or Batticaloa. The Sri Lankan civil war pitted the majority Sinhala-dominated security forces against the Tamil Tigers, who said they were fighting for a separate state for the country’s Tamil minority following discrimination and violence from successive Sri Lankan governments. Indeed, even before the war, Tamil people exited the country because of the actions of the state, and in the early years of the conflict, the number of Tamil refugees and emigrants rose dramatically. This means that if one uses the notion of lived experience as the only valid claim to authenticity, someone who grew up with Sinhala Buddhist majority privilege in Colombo—and with Sinhala Buddhist nationalist beliefs—could try to silence someone whose minoritized family left Sri Lanka because of those beliefs. And, in fact, this happens all the time.

I cannot countenance this. But what, then, is the importance of lived experience? As there are those who might decry me as inauthentic, there are others who assume I have credibility—who see no distinction between diaspora and homeland. I do not want this power either. Certainly, someone who has grown up in Sri Lanka has different stakes in what occurred than I do. And the politics of diasporas often skew away from what those in the place of origin want—even when those people in the diasporas trace their histories to the same communities. For example, certain strands of Tamil nationalism have long had a stronger hold outside the country; inside Sri Lanka, people have a clearer sense of the Tigers’ brutality as a mirror of the state’s.

How could I acknowledge the power of lived experience while simultaneously laying claim to my right to write about what I wanted?

As I considered writing about the war’s early years, I asked myself how I could acknowledge the power of lived experience while simultaneously laying claim to my right to write about what I wanted. I could not assume I knew my material if that material was Sri Lanka itself. The answer, I thought, would lie in books, and in other people. To write Brotherless Night, I attempted to throw a rope of research over an unbridgeable chasm, with a river of doubt running steadily underneath. I had lived through the war in time, and outside of it in space, and so I studied history the way a person of faith might have said a rosary: with belief, and as a kind of penance. I had a guess about who I was, and who I could have been, and set out to damn and verify myself.

*

Someone with these goals may find no better terrain than fiction. To damn myself: How much did I not know? To verify myself: How much could I check? In both cases, again, oceans. Without realizing it, I had grown up on the dueling propagandas of the Tigers and the state. Stories commonly told in the diaspora turned out to be incomplete or wrong. I stepped back from the precipice of unearned authority to try again.

In January 2004, almost 20 years ago, I was returning home from Sri Lanka. On my way back to the U.S., I stopped in London, where a relative who was a librarian gave me a copy of a rare book titled The Broken Palmyra, which records atrocities committed not only by the Sri Lankan state and its security forces, but also by the Tamil Tigers and Indian peacekeepers. Reading this book was the beginning of understanding how much I did not know.

Brotherless Night is a tribute to that book, a novel about ordinary people living at the edges of war, as people I knew had done, and as I imagined I might have done. The story centers on a young Tamil woman who lives in northern Sri Lanka in the early 1980s. Sashi dreams of being a doctor. But as communal tension grows, she sees two of her older brothers and a childhood friend join the Tamil Tigers. Sashi herself becomes a “helper” medic at a field hospital, but is horrified when the Tigers murder her beloved teacher. When Indian peacekeepers arrive, she is further disillusioned by their atrocities and turns to one of her medical school professors, a feminist and dissident who invites her to join in documenting human rights violations as a mode of civil resistance to war.

To write about Sashi, I needed to seize the knowledge history had taken from me. I followed the arrows of The Broken Palmyra into multiple university libraries, where I discovered no definitive takes, no unbiased reading. I held books up against each other, comparing one account to another, revealing one volume’s omitted fact in a second’s index. And people I spoke to who had lived through this era offered me versions I never saw in any books. As I worked, I learned to admire the meticulousness of The Broken Palmyra’s authors, the University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna), and Brotherless Night grew to encompass a fictionalized version of their story.

They are key to my heroine’s politicization, as they were key to mine. In real life, this group, four Tamil professors at the University of Jaffna, taught themselves how to document human rights violations during the war. They were critical of the state, but also critical of the Tigers, Indian peacekeepers, and the international community. Through reading their work, I came to believe that meaningful representation required self-critique. They wrote especially movingly and analytically about how the Tigers, a fascist movement, had arisen from Tamil society. Sashi’s professor in Brotherless Night, Anjali Premachandran, is based on Rajani Thiranagama, the only woman in the group and a professor of anatomy at the medical school.

In the end, my research brought me back to the place I had started: the first-person vantage point of Sashi’s life in 2009, when as an emergency room physician in New York, she follows from afar as Sri Lanka’s civil war hurtles to a brutal end. I had stopped asking if her voice belonged to me; I belonged to her. The prose employs intense realism and direct address to draw on decades of research, including engagements with civilians who endured this period of the war; former militants; journalists; human rights defenders; and scholars of anthropology, human rights, law, and literature; as well as my own experience living in New York in the spring of 2009.

The novel traces Sashi’s moral and political journey, and explores martyrdom, oppression, resistance, and different forms of exile. The experiences of Tamil women—specifically, civilians, students, and dissidents—take center stage. The book underlines events and complexities commonly and intentionally erased from various nationalist narratives. It also contends with the aftermath of the war, its massive civilian casualties, and its allegations of war crimes—as well as how journalism and the international community failed Tamil civilians at the conflict’s end.

Brotherless Night aims to portray characters at the margins of the conflict, especially individuals who were not officially in militant groups, but were near enough to them to experience a combination of sympathy and coercion. People moved in and out of political alliances and affiliations; it was not always clear who was involved and how and whether it was voluntary. People informed on each other—for the state, the Indians, and the Tigers. Surveillance also happened in the diaspora. I am interested in writing about the effects of this surveillance on my communities, which over the course of the war experienced mass casualties and repeated displacements. I am interested partly because—justifiably or not—I feel surveilled myself. I say this to note: I can tell you that I have a personal history, but I cannot always give it to you. Research and fiction have offered me a way through.

*

If the library is a religion, perhaps I am a person of faith. I thought that even if my fictional sentences told the truth to no one else, they might tell the truth to me. How far could studying take me towards understanding what had happened? Not at all the way, but close to a line mapping infinity. This book and its research have taken half my life, which seems the right accounting, given how much life the war itself took.

And rather than being a history I lived, or one I assumed, Brotherless Night has become the history I sought out, the history I chose to learn well enough to imagine. You can see where I stand, here on this diasporic edge, so what else could I do to help you believe the story I am telling? To believe it myself? I want you to understand: I walked the path of what I inherited and then crossed the slender bridge over the river into the country of what I did not know.

_____________________________

V. V. Ganeshananthan’s Brotherless Night is available now from Random House.

V.V. Ganeshananthan

V. V. Ganeshananthan is the author of Love Marriage, which was longlisted for the Women’s Prize and named one of the best books of the year by The Washington Post. Her work has appeared in Granta, The New York Times, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading, among other publications. A former vice president of the South Asian Journalists Association, she has also served on the board of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, and is presently a member of the board of directors of the American Institute for Sri Lankan Studies and the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. She teaches in the MFA program at the University of Minnesota and co-hosts the Fiction/Non/Fiction podcast on Literary Hub, which is about the intersection of literature and the news. Her new book Brotherless Night is available now.