On Agatha Christie and the Dawn of a Post-Capitalist Era

A Close Reading of Christie's 80th book, Passenger to Frankfurt, by Slavoj Žižek

Agatha Christie’s 80th book, Passenger to Frankfurt—published in 1970 with the subtitle “an extravaganza,” one of the few of her works with no movie or TV adaptation—is a novel that “slides from the unlikely to the inconceivable and finally lands up in incomprehensible muddle. Prizes should be offered to readers who can explain the ending. It concerns the youth uproar of the “sixties, drugs, a new Aryan superman and so on, subjects of which Christie’s grasp was, to say the least, uncertain.” However, this “incomprehensible muddle” is not due to Christie’s senility: its causes are clearly political.

Passenger to Frankfurt is Christie’s most personal, intimately felt and at the same time most political novel; it expresses her personal confusion, her feeling of being totally at a loss with what was going on in the world in the late 1960s—drugs, sexual revolution, student protests, murders, etc. It is crucial to note that this overwhelming feeling of confusion is formulated by an author whose specialty was detective novels, stories about crime, stories about the darkest side of human nature.

The deeper reason for her despair is the feeling that, in the chaotic world of 1970, it was no longer possible to write detective novels that still presupposed a stable society based on law and order, momentarily disturbed by crime but restored to order by the detective. In the society of 1970, chaos and crime were rife, so no wonder Passenger to Frankfurt is not a detective novel: there is no murder, no logic, no deduction. Christie’s sense of the collapse of the elementary cognitive mapping, her overwhelming fear of chaos, is rendered clearly in her Introduction to the novel:

It is what the Press brings to you every day, served up in your morning paper under the general heading of News. Collect it from the front page. What is going on in the world today? What is everyone saying, thinking, doing? Hold up a mirror to 1970 in England.

Look at that front page every day for a month, make notes, consider and classify.

Every day there is a killing. A girl strangled.

Elderly woman attacked and robbed of her meagre savings. Young men or boys—attacking or attacked.

Buildings and telephone kiosks smashed and gutted. Drug smuggling.

Robbery and assault.

Children missing and children’s murdered bodies found not far from their homes.

Can this be England? Is England really like this? One feels—no—not yet, but it could be.

Fear is awakening—fear of what may be. Not so much because of actual happenings but because of the possible causes behind them. Some known, some unknown, but felt. And not only in our own country. There are smaller paragraphs on other pages—giving news from Europe—from Asia—from the Americas—Worldwide News.

Hi-jacking of planes. Kidnapping.

Violence. Riots.

Hate.

Anarchy—all growing stronger.

All seeming to lead to worship of destruction, pleasure in cruelty. What does it all mean?

So what does all this mean? In the novel, Christie provides an answer; here is the storyline. On a flight home from Malaya, Sir Stafford Nye, a bored diplomat, is approached in the passenger lounge at Frankfurt airport by a woman whose life is in danger; to help her, he agrees to lend her his passport and boarding ticket. In this way, he unwittingly gets caught up in an international intrigue from which the only escape is to outwit the power-crazed Countess von Waldsausen, who wants to achieve world domination by manipulating and arming the planet’s youth.

This terrible worldwide conspiracy has something to do with Richard Wagner and “The Young Siegfried.” We learn that, towards the end of the Second World War, Hitler went to a mental institution, met with a group of people who thought they were Hitler, and exchanged places with one of them, thus surviving the war. He then escaped to Argentina, where he married and had a son who was branded with a swastika on his heel: “The Young Siegfried.” Meanwhile, in the present, drugs, promiscuity and student protests are all secretly caused by Nazi agitators who want to bring about anarchy so that they can restore Nazi domination on a global scale.

Is this disgusting fantasy, which brings together anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, so different from that contrived by Christie?

This “terrible worldwide conspiracy” is, of course, ideological fantasy at its purest: a weird condensation of the fear of extreme Right and extreme Left. The least we can say in Christie’s favor is that she locates the heart of the conspiracy in the extreme Right (neo-Nazis), not any of the other usual suspects (Communists, Jews, Muslims). The idea that neo-Nazis were behind the ’68 student protests and the struggle for sexual liberation, with its obvious madness, nonetheless bears witness to the disintegration of a consistent cognitive mapping of our predicament; the fact that Christie is compelled to take refuge in such a crazy paranoiac construct indicates the utter confusion and panic in which she found herself.

The picture of our society she paints is simply confused, out of touch with reality (incidentally, although to a much lesser extent, the same goes for the strangest of John le Carré’s novels, A Small Town in Germany, which is set in a similar situation). But is her vision really too crazy to be taken seriously? Is our era, with “leaders” like Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un, not as crazy as her vision? Are we today not all like a bunch of passengers to Frankfurt? Our situation is messy in a way that is very similar to the one described by Christie: we have a Rightist government enforcing workers’ rights (in Poland), a Leftist government pursuing the strictest austerity politics (in Greece). No wonder that, in order to regain a minimal cognitive mapping, Christie resorts to the Second World War, “the last good war,” retranslating our mess into its coordinates.

One should nonetheless note how the very form of Christie’s denouement (one big Nazi plot behind it all) strangely mirrors the fascist idea of the Jewish conspiracy. Today, the extreme populist Right proposes a similar explanation of the Muslim immigrant “threat.” In the anti-Semitic imagination, the “Jew” is the invisible Master who secretly pulls the strings—which is precisely why Muslim immigrants are today’s Jews: they are all too visible, not invisible, they are clearly not integrated into our society, and nobody claims they secretly pull any strings. If one sees in their “invasion of Europe” a secret plot, then Jews have to be behind it—as was suggested in an article that recently appeared in one of the main Slovene Rightist weekly journals, which read: “George Soros is one of the most depraved and dangerous people of our time,” responsible for “the invasion of the negroid and Semitic hordes and thereby for the twilight of the EU . . . as a typical talmudo-Zionist, he is a deadly enemy of Western civilization, nation state and white, European man.” His goal is to build a “rainbow coalition composed of social marginals like faggots, feminists, Muslims and work-hating cultural Marxists,” which would then perform “a deconstruction of the nation state, and transform the EU into a multicultural dystopia of the United States of Europe.” Furthermore, Soros is inconsistent in his promotion of multiculturalism:

He promotes it exclusively in Europe and the USA, while in the case of Israel, he, in a way which is for me totally justified, agrees with its monoculturalism, latent racism and building of a wall. In contrast to EU and USA, he also does not demand that Israel open its borders and accept “refugees.” A hypocrisy proper to Talmudo-Zionism.

Is this disgusting fantasy, which brings together anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, so different from that contrived by Christie? Are they both not a desperate attempt to orient oneself in confused times? The extreme oscillations in public perception of the Korean crisis are significant as such. One week we are told that we are on the brink of nuclear war, then there is seven days’ respite, then the war threat explodes again.

When I visited Seoul in August 2017, my friends there told me there was no serious threat of a war since the North Korean regime knows it could not survive it, now that the South Korean authorities are preparing the population for a nuclear war. Not long ago our media was reporting on the increasingly ridiculous exchange of insults between Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump. The irony was that, in a situation where two apparently immature men are getting angry and hurling insults at each other, our only hope is for some anonymous and invisible institutional constraint to prevent their rage from exploding into full war. Usually we tend to complain that in today’s alienated and bureaucratized politics, institutional pressures and constraints prevent politicians from expressing their real point of view; now we hope that such constraints will prevent the expression of all-too-crazy personal visions. How did we reach this point?

Alain Badiou recently warned about the dangers of the growing post-patriarchal nihilist order that presents itself as the domain of new freedoms. The disintegration of the shared ethical basis of our lives is clearly signaled by the abolition of universal military conscription in many developed countries: the very notion of being ready to risk one’s life for a common-cause army appears more and more pointless, if not directly ridiculous, so that the armed forces, as the body in which all citizens equally participate, are gradually becoming a mercenary force. This disintegration affects the two sexes differently: men are slowly turning into perpetual adolescents, with no clear passage of initiation into maturity (military service, acquiring a profession, even education no longer play this role). No wonder, then, that, in order to supplant this lack, post-patriarchal youth gangs proliferate, providing ersatz-initiation and social identity.

In contrast to men, women today are more and more precociously mature, expected to control their lives, to plan their careers; in this new version of sexual difference, men are ludic adolescents, outlaws, while women appear hard, mature, serious, legal and punitive. A new feminine figure is thus emerging: a cold, competitive agent of power, seductive and manipulative, attesting to the paradox that “in the conditions of capitalism women can do better than men” (Badiou): contemporary capitalism has invented its own ideal image of woman.

__________________________________

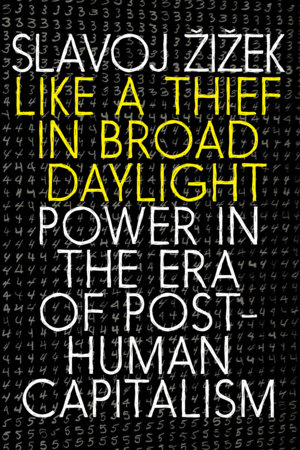

Excerpted from Like A Thief In Broad Daylight: Power in the Era of Post-Human Capitalism by Slavoj Žižek, published by Seven Stories Press, September 17, 2019.

Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek is a Hegelian philosopher, Lacanian psychoanalyst, and political activist. He is the International Director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities and Eminent Scholar at Kyung-Hee University, Seoul. His previous books include Living in the End Times, First as Tragedy, Then as Farce, Trouble in Paradise, The Courage of Hopelessness, and most recently, Like A Thief In Broad Daylight.