Omer Friedlander and Joshua Henkin on Writing with a Sense of Place

“When you find the right detail ... it comes to life.”

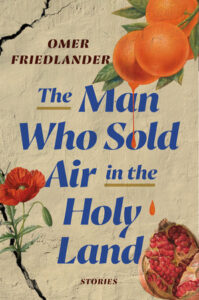

I was sent Omer Friedlander’s debut story collection, The Man Who Sold Air in the Holy Land, out of the blue by his editor Robin Desser. The truth is that several bouts of covid in my household and work responsibilities kept me from getting to it right away, but when I did start reading I was astonished by the uniqueness of the characters and the world-building in these stories. They have a touch of magic reminiscent of I.B. Singer and Nathan Englander. It was a great pleasure to talk with Omer about the craft of short story writing, the power of place, and the practice of writing between languages.

–Joshua Henkin

*

Joshua Henkin: You’ve spoken about writing this collection in English, which is your second language, rather than Hebrew, your mother tongue. Why did you make the decision to write it in English?

Omer Friedlander: I’m not sure it was a conscious decision to write in English. When I was six years old, I moved with my family to New Jersey for two years. That’s where I learned English. It was also the very first time I rode a bus. Growing up in Israel during the Second Intifada my parents didn’t let me get on a bus. There were suicide bombers and it was very dangerous. I remember feeling very excited when I got on a bus for the first time in America, even though it was very ordinary for everyone else.

I was actually so excited that I spilled a bottle of coke I was drinking, and it rolled down the aisle and made everything sticky and everyone pretty angry. But I didn’t care—I was on a bus! I get a similar feeling with writing, or telling a story. Being able to do something new. It’s like riding the bus for the first time, it’s exciting.

JH: Tell me how this book came together as a collection. What was the first story you wrote, and what was the most recent? How did you and your editor (Robin Desser) decide which stories to include, and in which order?

OF: The first story I wrote in the collection was Walking Shiv’ah. It’s a story about a mother who wants to sit shiv’ah for her missing sons, except she doesn’t know if they are dead or alive. It was inspired by my maternal grandfather’s family story. He grew up far, far away from the Middle East, in the polite, snowy wasteland of Montreal. His family originally came to Canada from Belarus. His grandfather boarded a ship first, to find work in the fur industry, and send money back to his wife and infant children, and several months later they were supposed to board a ship, and join him in Canada.

When the time came for his wife and kids to board the ship, they had the incredibly lucky misfortune of missing their departure. While heaving the various bags and suitcases aboard the ship together with the burly, vodka-chugging dockworkers, the wife forgot, in her haste and anxiety, one child’s precious and expensive violin at home. They decided to send the suitcases ahead on the voyage, and board the next ship, leaving in a week’s time, with the violin. The ship, which luckily they did not board, sunk. All of the passengers perished. My grandfather’s grandfather, hearing about the terrible incident, mourned and sat shiv’ah for his wife and children for a week, when suddenly they appeared, alive and well, at his doorstep, clutching the precious violin.

The last story I wrote was “The Miniaturist.” It has multiple sources of inspiration. The first was meeting two Jewish-Iranian brothers at a small shop on Ben-Yehuda street in Tel Aviv. They sold carpets, made by their elderly mother, and also beautiful vases, painted with fish and flowers. I began talking to the brothers, and they told me about some of their experience immigrating to Israel from Isfahan, a city in Iran known for its textiles and carpets.

The second source of inspiration was my maternal grandmother, who came to Israel from Egypt. She grew up in Alexandria. Her family was originally from Syria and Morocco, and could be traced all the way back to the golden age of Jews in Spain, before the Alhambra Decree of Isabella and Ferdinand forced them into exile. When she came to Israel with her family, at the age of sixteen, she was sent to a Ma’abara (like the protagonist of my story), an immigration absorption camp, with the most terrible living conditions in tents, with limited water and sewage running openly. She spent almost a year in the tent-city, and still can barely talk about that time.

“There is no usual starting point, because every story must be discovered in its own way.”

Some of your work has been inspired by your family, too, right? I read an interview where you said that Morningside Heights was inspired by the time your mother started going to a class for caregivers at the JCC in Manhattan, after your father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s?

JH: Yes, that’s true. Morningside Heights started as a long short story that took place at the JCC at a class for caregivers. Eight years and many dozens of drafts later, the JCC and most of the characters at the JCC were gone. But then that’s always how it works for me You never end up where you think you’re going. If there’s no surprise for the writer, then there’s no surprise for the reader. Is that where most stories “start” for you—from a character? I know some writers start from a situation or an emotion.

OF: It really depends on the story. There’s a brilliant essay by Zadie Smith called “That Crafty Feeling” where she talks about feeling like a fraud whenever she talks about craft. Craft isn’t abstract, she says, and “each individual novel is its own rule book, training ground, factory, and independent republic.” I feel the same about each story I write. There is no usual starting point, because every story must be discovered in its own way, it must teach you to read it on its own terms.

Robin and I also discussed the order of the stories quite a lot. It’s a very intuitive decision. We thought of it almost like a music album. We wanted to balance the tone, funny or sad, and we also considered the narrator, and if it was written in first or third person. Opening with “Jaffa Oranges” sets the scene for the entire collection, roots us very firmly in place. And we end with “The Miniaturist” which is a story that begins in 1950 and ends in 2013, it covers a lot of ground, an entire life, and is framed by two of Israel’s biggest snowstorms of the last century. I wanted it to begin and end with snow, something you wouldn’t associate with Israel, a rare event.

JH: I like the album analogy—in good albums each song stands on its own but also plays a part in the larger story.

OF: Exactly. What was the writing process like for Morningside Heights?

JH: Highly inefficient. The book took me eight years to write and I wrote 3,000 pages, 2,700 of which ended up on the cutting-room floor. I wish I could do it differently, but that’s just how I write. To me, fiction is about character, and I need to write a lot of pages to discover who my characters are. So how did your stories move from stories to book? How did the book deal happen?

OF: The book-deal talks with editors coincided with a weekend trip I took to a small village in the Galilee. My twin brother and I celebrated our twenty-sixth birthday there—a small, very remote village with no phone signal, internet or electricity. It was very beautiful—plenty of limestone and groves of olive trees—but probably the worst place to go to on this weekend when I had to talk on the phone to several editors.

My father and I drove around to look for a place with reception and finally we found a hookah bar by a gas station off the highway, overlooking a barn. I ended up making all my calls to editors from the parking lot of the hookah bar, with teenagers revving their motorcycle engines in the background. In any case, it all worked out.

JH: I can picture that exactly from that story—which isn’t surprising, because you really excel at putting the reader in the scene. Reading these stories, one has an almost hallucinatory sense of place—the settings are really a part of the fabric of the book. Was that conscious when you were writing them?

OF: A strong sense of place can really guide a story. Any kind of fictional story you write is fragile, especially in the beginning, in the early stages of drafting. But when you find the right detail, the invented world slowly becomes more substantial and real, it comes to life both in your mind and the reader’s. Some of the books I’ve enjoyed reading the most have this vividness, a specificity of place. Your work is very connected to place, too. Morningside Heights obviously, but also The World Without You which is set in a summer home in the Berkshires. What are you writing next and is it centered around place in some way?

JH: All my work ends up being centered around place, but I never start with place. I always start with character, but because my characters are almost invariably rooted in a place, place becomes important. I’m working on three different projects right now.

One is a first-person novel that takes place in contemporary New York City and that is driven by a speculative premise, which is a departure for me. I’m also working on a much longer novel that chronicles four generations of an American Jewish family over more than a century. The book starts in Belarus in the late 19th century and ends in Tel Aviv shortly after Joe Biden is elected, but the bulk of it takes place in between—on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the 1930s and 1940s, at Harvard in the 1950s and 1980s, in Washington, D.C., in the 1960s, in New Haven in the 1970s, and in Los Angeles and the Pacific Northwest in the 1990s.

And in between all that, I’m working on a collection of stories, each of which takes place in a different neighborhood in New York City. So in that one, for sure, I’m thinking a lot about place!

“When you find the right detail, the invented world slowly becomes more substantial and real, it comes to life both in your mind and the reader’s.”

JH: Allusions to fables and fairytales occur throughout these stories—why was it important to you to reference the fantastical in this collection?

OF: My interest in fables and fairy tales comes from my father, who collects old, illustrated children’s books. When I was growing up, I remember my father going to flea markets and used bookstores to scavenge for these books. What I find exciting about fairy tales is that they offer the possibility of metamorphosis, shapeshifting, of change and transformation, beyond the boundaries of what we conventionally call “real.”

JH: Speaking of metamorphosis—did the collection change much while you were editing?

OF: When I was working on the collection, with each revision I was searching for the shape of the story, until I found the most natural way of telling it. I like Truman’s Capote’s idea of a good short story. He says it’s like an orange, it feels so natural you can’t imagine it any differently. And I love oranges—just look at my book cover.

*

Omer Friedlander was born in Jerusalem in 1994 and grew up in Tel Aviv. He earned a BA in English literature from the University of Cambridge, England, and an MFA from Boston University, where he was supported by the Saul Bellow Fellowship. His short stories have won numerous awards and have been published in the United States, Canada, France, and Israel. A Starworks Fellow in Fiction at New York University, he has earned a Bread Loaf Work-Study Scholarship as well as a fellowship from the Vermont Studio Center. He currently lives in New York City.

Joshua Henkin’s most recent novel, Morningside Heights, comes out in paperback on May 24. It was named the Book of the Year by the Chicago Tribune. It was longlisted for the Joyce Carol Oates Prize, selected by the American Booksellers Association as the #1 Indie Next Pick, and named an Editors’ Choice Book by The New York Times. He directs and teaches in the MFA Program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College.

__________________________________

The Man Who Sold Air in the Holy Land: Stories by Omer Friedlander is available via Random House.