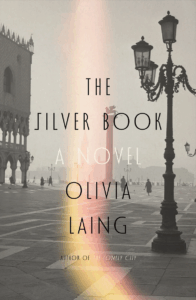

Olivia Laing on Fictionalizing the Murder of Pier Paulo Pasolini

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of The Silver Book

Olivia Laing’s innovative first novel Crudo (2018), winner of the James Tait Black Memorial prize, is written from the point of view of Kathy Acker, who Laing called “the acme of the self-invented, self-mythologizing counterculture superstar, a foulmouthed Beat biker and bodybuilder dressed in Comme des Garçons, child of the Marquis de Sade and Wild Bill Burroughs.” From the opening lines of Crudo—“Kathy, by which I mean I, was getting married. Kathy, by which I mean I, had just got off a plane from New York.”—Laing inhabits Acker, explores her fakeries, extends her life beyond her death by cancer which she treated with unorthodox approaches; she blurs and blends, reacts, emotes.

There’s an intriguing alignment between Acker’s novel My Death, My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini, in which Pasolini ties his murder to his anti-fascist perspective, and Laing’s second novel, The Silver Book, which revolves around cinematic artists Federico Fellini and Pier Paolo Pasolini, both working on ground-breaking projects (Casanova and Salò) at Cinecittà in Rome during the months before Pasolini’s death in 1975.

What motivated you to write this novel about Fellini, Pasolini, and their Cinecittà colleague Danilo Donati? I asked Laing via email. “I was very interested in Pasolini’s murder,” Laing explained.

I’d wanted to write a thriller for a long time and in 2023 I made a series of fortuitous discoveries. I came across the story about the stolen reels from Salò, Pasolini’s apocalyptic final film, and how they might have been used to lure him to his death. And then I realized reels had also been stolen from Fellini’s Casanova, and that the same incredible designer, Danilo Donati, was working on both films.

That coincidence gave me my setting. I wanted to explore the fascinating world of cinema in the 1970s, this place of perpetual illusion, and the strange role Pasolini played within it. He was someone who could see through illusion to the truth, and I think that was why he was killed. His message about fascism feels extremely relevant now. At the same time, this is a novel about creativity, especially very hand-made and collaborative creativity. And it’s about queer people finding a world to thrive in. Both things feel vital amid the global rise of hatred, and the crisis of the imagination that is AI.

*

Jane Ciabattari: When did you first encounter the films of Fellini and Pasolini? What was your first reaction? Has your perception of their films changed over the years?

Olivia Laing: There was a poster of La Dolce Vita in my teenage bedroom. I love them both. Fellini is the great dreamer, who understands human aspirations and failings. And Pasolini is the poet who possessed total clarity about political systems, and especially the damage capitalism would do to the environment, to society, to how people interact with each other. To me, they both seem more significant than ever.

JC: How did you settle on the title of this novel?

OL: It came to me in a flash, in a water taxi leaving Venice, out on the lagoon, along with the idea for the book. Silver for the silver screen, silver for illusion and deception, for things that tarnish and things that shine.

JC: What led you to choose Donati (“Of Fellini is the maestro, he is the magician, stirring his cauldron in the back room,” you write) and Nicholas, Donati’s much younger English lover, as key narrators?

OL: I really did have a vision of them both. I saw Donati encountering a beautiful red-headed English boy on the steps on San Vidal church in the Campo Santo Stefano, and a bolt passing between them. A grand love affair that brought chaos in its wake. That was in the summer of 2023, and I couldn’t start writing for another year, so I just visited them in my mind, letting them develop and become clearer and clearer.

JC: How did you develop Nicholas’ back story? Is it based on real life, as are the Fellini and Pasolini sections?

OL: A friend Googled him, which pleased me.

JC: Did you travel to Venice, Rome, Ostia, and other locations to write the scenes you set in such detail—the hustlers at Termini, Villa Feltrinelli, Pasolini’s home, Donati’s Venetian hotel room, feasts prepared by Donati, his mother’s home, and others?

Something different happened, which isn’t at all the same as non-fiction. What you put in is not what comes out.

OL: Some of these places are real, and some aren’t. Some of them I visited in 2024, but the novel is set in 1975, so it’s all an act of time travel, of reanimating scraps and glimpses to try and summon up a real world. I did live in Rome while I was writing it, but it was never quite the same city I describe.

JC: Did you spend time on film sets, studio lots, and watching films and documentaries to develop details for Fellini’s Casanova, set in Venice, and Salò, Pasolini’s allegory of fascism? (I’m thinking of the scene where Nicholas first meets Fellini, the details of the work of these film crews. Donati’s listing of the dyes he will use to make 3,000 costumes.)

OL: I have never been on a film set, but I watched a lot of documentaries. Memoirs, diaries. And then—I don’t know. Something different happened, which isn’t at all the same as non-fiction. What you put in is not what comes out.

JC: You present an ongoing conflict as Fellini directs Canadian actor Donald Sutherland, intentionally subjecting him to pressure and pain to elicit a specific performance. Sutherland has given at least one interview (in 1976) in which he says that the actor creates the character in theater, but director creates the character in cinema. The actor must “understand the character and participate,” he says. “Fellini conjures up all these wonderful images and it makes the work easier,” because it’s obvious what he wants. How did you go about developing the fictional version of the artistic relationship between Fellini and Sutherland?

OL: Oh Donald! I’m a big fan of both of them, but it was very easy to imagine how unsatisfactory a relationship between two such opposite temperaments would be. Fellini was a bully and Sutherland was a control freak. It wasn’t a happy marriage, but it did create an extraordinary film.

JC: What sort of research did you do into Pasolini’s death? How was it possible to select the motivation (speculation has included murder, assassination)?

As for the challenges, I think they were the same as ever: to do justice to people, to catch something of their essence.

OL: I think the consensus now is that Pasolini wasn’t murdered by Giuseppe Pelosi, but rather by a group of people, almost certainly on instruction. It’s my belief, as it is for many people in Italy, that this was an assassination because of the columns he was writing in Corriere and his forthcoming novel, Petrolio, in which he promised to identify the people responsible for widespread right-wing corruption and violence in Italy.

What he kept describing, in both his writing and his final film, was the fact that fascism would return in a new form, a fascism horribly wed to capitalism. He foresaw a frightening future, and he warned particularly about the lethal danger of compliance and complicity. That’s really what Salò is about. It’s plausible that the stolen reels were used to lure him to his murder, and that’s the story I chose to fictionalize. This is a novel, but when Pasolini speaks at the end, on the night of his death, I used his own words. The dangers he was describing: look around. I didn’t make them up.

JC: On Instagram you posted “I’ve never had such a wild time writing anything.” What did you mean? What were the challenges of writing about “real” people in this historic novel?

OL: It was a wild experience because of the speed that it came out. I literally couldn’t type fast enough, and by the end was working from dawn until the small hours. It was as if I was taking dictation, and I’ve written enough books to know what a rare experience that is. The kind of non-fiction I write is archive-based and glacially slow. This was at fever pitch. As for the challenges, I think they were the same as ever: to do justice to people, to catch something of their essence.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

OL: My first novel Crudo was the beginning of a quartet, written at decadal interviews, an attempt to chart the crazy political and social climate of the Anthropocene. It was written in 2017, so I’m approaching the next one and there’s certainly no shortage of material. And I have a book about to come out that gathers together my long-term collaboration with the painter Chantal Joffe. Hang on—if we count that as half a book then The Silver Book is literally my 8½. How appropriate.

__________________________________

Olivia Laing will be in conversation with Rachel Kushner at a virtual event with the Center for Fiction on November 11th at 7 p.m. ET. You can register for the talk here.

__________________________________

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing is available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.