Office Culture Follows Us Everywhere: Six Books About Work

Daniel Poppick Recommends Kathryn Scanlan, Vivian Gornick, Franz Kafka, and More

Office culture follows us around. Working for a startup, a big corporation, a personal brand, or in the gig economy, it’s hard not to feel the gravitational pull of the grindset—and its shadow, unemployment. This isn’t new, of course. Capitalism has historically put a border between life and making a living, and while we try to maintain equilibrium between the two, one is always spilling into the other.

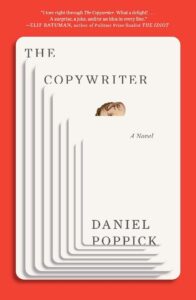

One of the ideas that was on my mind while I was writing my novel, The Copywriter, is that work, like a poem you memorize in school, sticks with you. By no means an exhaustive list, below are seven books that helped give the idea shape.

*

Kathryn Scanlan, Kick the Latch

In this novella about an Iowa woman’s lifelong career training horses, the most haunting characters are the horses themselves: an unpaid shadow workforce at the racetrack, the rodeo, and in stables, empathically and mysteriously buoying the human souls who love them. At times, Kick the Latch seems to suggest that injured racehorses and their exhausted caretakers might share a parallel fate. “Priests came on race days to bless the horses’ legs before they ran,” Scanlan’s shrewd narrator observes, “but there’d be plenty of times it didn’t work.” Everywhere you go, even and especially if they can’t speak, somebody is always working.

Helen DeWitt, Lightning Rods

A travelling salesman struggles to make ends meet selling encyclopedias and vacuum cleaners when an idea strikes him—a potentially revolutionary idea—for an invention that stands to boost employee productivity and solve the problem of sexual harassment in the office. Reading DeWitt’s gleefully acidic satire in 2026, at a moment when AI is being embraced by an executive class seemingly eager to alienate and hasten the obsolescence of the human labor market, it is difficult not feel a shiver of recognition in the story of a man rising through the ranks of corporate America selling what essentially amounts to a high-tech glory hole.

Samuel R. Delaney, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue

While miles apart in tone and character, Lightning Rods pairs weirdly well with Times Square Red, Times Square Blue in the pantheon of books about public sex and the mind-numbing effects of corporate logic. Part memoir, part reportage, part scholarly criticism, Delaney’s account shows how the sex economy around the old Times Square—the porn theaters, adult video stores, and sex workers that Mayor Giuliani power-washed away in the ‘90s, along with the food carts and vendors who catered to them—created a delicate web of social relationships across race and class in a city where gentrification has made genuine human contact of this nature vanishingly rare.

Vivian Gornick, The Romance of American Communism

A friend of mine sometimes jokingly refers to her position as a leader in her workplace’s union as “my job about my job.” This also feels apt for the voices in Gornick’s oral history of the American Communist Party—told by the people who lived through its peak years of influence in the ‘30s,‘40s, and early ‘50s, and its precipitous decline during the McCarthy era and the Cold War. The more obvious pick for an oral history on the subject of work from the ‘70s would probably be Studs Terkel’s Working, but Gornick’s book about the inner lives of socialists is profoundly moving for how it illuminates its subjects’ devotion to one another: the job about their jobs. As one of Gornick’s interviewees says, “it was like I was discovering the world for the first time… The shapes of the buildings, the way the streets looked after a rain, the expressions on people’s faces… I’d look around the room at these guys, and they were my comrades, and I loved them so hard I thought I’d burst with it.”

Sylvia Townsend Warner, The Corner That Held Them

Imagine if, instead of serving as the regional manager of a paper company, Michael Scott faked his way into a job as a priest at a backwater Benedictine convent in the English fens during the Black Death. The Corner That Held Them is a historical novel following the lives of the nuns who pass through the fictional convent of Oby in the 14th century, until the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Warner, a historian by training and a member of the British Communist Party, avoids Catholic spirituality almost completely, focusing instead on the nuns’ daily gruntwork: preparing meals, cleaning up after a collapsed spire, jockeying for favor with the prioress, attending to “an extravaganza of death.” The result is plotless, tonally pristine, and utterly absorbing, a bone-dry workplace comedy of the highest (monastic) order.

Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis

You sleep through your alarm and the next thing you know you can’t eat, you’re a burden to your family, and an apple is festering in your exoskeleton. Mondays, amiright?

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Unlike Bartleby, Ishmael would not prefer not to: a hard worker who keeps his head down, he holds a second job as a recording angel for the reader. At one point our narrator overhears Stubb telling Flask that he dreamed that Ahab, their doomed CEO, was a pyramid. In some sense the mystery of Moby-Dick lies not in the whiteness of the whale but in how Ishmael manages to overhear so much on the Pequod, that paradigmatic floating office of American literature. Who is surveilling whom? Stubb’s dream is a little on the nose, but Ahab does serve as a monument to the rapacious pursuit of profit on this intimate vessel as it sails across the watery void.

__________________________________

The Copywriter by Daniel Poppick is available from Scribner.

Daniel Poppick

Daniel Poppick is the author of the poetry collections Fear of Description, a winner of the National Poetry Series, and The Police. His writing appears in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The New Republic, The Yale Review, BOMB, and elsewhere. He works as a copywriter and lives in Brooklyn.