Of Womb-Furie, Hysteria, and Other Misnomers of the Feminine Condition

Clare Beams on Women's Bodies and the Power of Names

Sometimes the strange actions of the body in question are taken for a name. The Dancing Plague, for instance, in which 400 people, in the streets of Strasbourg, in 1518, danced to the point of exhaustion and sometimes to death. (It’s difficult at first to believe that a person could do this, dance herself to death, but I find with concentration I can almost imagine it, almost feel it somewhere in the soles of the feet and in the lungs, what it might be like to be forced to go on and on until giving out like an overwound clock.) Also the Writing Tremor Epidemic: in Poland in 1892, a schoolgirl’s writing hand was afflicted by trembling, and then the writing hands of the other schoolgirls. And the Laughing Plague: in 1962, in Tanganyika, a group of schoolgirls laughed and laughed and couldn’t stop.

Alternatively, the ailment is sometimes named for a place. Salem, for instance, now stands in not just for the Witch Trials (though they are related) but also for the original fits of the girls, before scapegoats were held accountable for them. Or LeRoy, New York, where a group of high school girls began twitching and laughing and fainting in 2011.

An effort at other times is made to name the actual affliction. Hysteria worked better when we believed wombs could wander and when we didn’t care so much about terms’ patronizing flavor. Psychogenic illness is a more current choice, or conversion disorder. Both word-packages deliver the same idea: here we have a problem in the body that does not originate in the body.

What is not generally on the table—not for group plagues, not for the long trail of singular afflicted winding through history—is naming the suffering after the sufferer him or herself. (Mostly herself.)

In his famous 1905 case study on the subject, Dora: An Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, Freud of course does his best to obscure his patient’s identity. He does, though, assert his right to describe her full body in discussing her symptoms and his interpretation of them. “Now in this case history … sexual questions will be discussed with all possible frankness, the organs and functions of sexual life will be called by their proper names … I will simply claim for myself the rights of the gynaecologist.” He wasn’t one, of course. Still, if he wanted to actually say anything, he was probably right to claim these terms for himself.

The use he makes of them, though—there it is possible to take some issue. His patient, 18-year-old Dora, is suffering from a battery of hysterical symptoms (difficulty breathing, a nervous cough, “hysterical unsociability,” etc.), and in analyzing her Freud uncovers an incident he suspects may be related to them: when Dora was 14, her father’s friend Herr K “suddenly clasped the girl to him and pressed a kiss upon her lips.” I have ideas about what to call this and how to understand it. Freud has different ones: “This was surely just the situation to call up a distinct feeling of sexual excitement in a girl of 14 who had never before been approached.” (What??? my college self wrote here in the margin.) Instead Dora felt revulsion, in what Freud terms a “reversal of affect,” and even years later still seemed sometimes to “feel upon the upper part of her body the pressure of Herr K’s embrace.”

These wandering wombs and Womb-Furies and hysterias and the treatments for them, have been named by men, most of the time.

It’s at this point in his analysis that Freud really begins putting his defended terminology to work. “I believe that during the man’s passionate embrace she felt not merely his kiss upon her lips but also the pressure of his erect member against her body. This perception was revolting to her; it was dismissed from her memory, repressed, and replaced by the innocent sensation of pressure upon her thorax…” And, presto, the haunting feeling that Herr K is still embracing her! Of course.

As for what Dora believed about her own illness, Freud writes, “It is of course not to be expected that the patient will come to meet the physician half-way with material which has become pathogenic for the very reason of its efforts to lie concealed; nor must the inquirer rest content with the first ‘No’ that crosses his path.” She doesn’t know the truth, in other words, and whatever she does know she certainly won’t say, and so the doctor just has to work harder to get her to disclose it, even—especially—if she doesn’t want to, for her own good.

This sense that the hysteric could not be trusted to understand or provide information about her own illness, or about much of anything—that she was by definition unreliable—was already an old one when Freud was treating and writing about Dora. In her book The Technology of Orgasm, Rachel P. Maines includes the observation of physician Albert Hayes, writing in 1869, that “the strength of the reproductive force… irradiates every part of the frame… when disordered by whatsoever cause, it becomes capable of carrying confusion into every department, where it may rave and rage in its caprice and fury.” The hysterical woman was made crazy by this congestion and overabundance. Her craziness stemmed directly from her sexuality, from her femaleness—from too much of it. Here’s an even older account, from the 17th-century physician Riverius: “Womb-Furie is a sort of madness, arising from a vehement and unbridled desire of Carnal Imbracement, which desire disthrones the Rational Facul[ty] so far, that the Patient utters wanton and lascivious Speeches…”

Given this understanding, a potential treatment suggested itself. Here’s Riverius again: “…some advise that the Genital Parts should be by a cunning Midwife so handled and rubbed, so as to cause an Evacuation of the over-abounding Sperm” (sperm here meaning the female body’s own secretions).

Maines’ argument in The Technology of Orgasm is that Victorian doctors’ frustration with the time-consuming nature of this kind of “massage” was what led to the invention of the vibrator. There isn’t consensus on an explicit link between these two, nor on how common a treatment for hysteria pelvic massage was during that era (though certainly it did exist). Part of the trouble with reaching such a consensus is that, as Maines herself says, “Physicians were less likely than their predecessors, who could draw the veil of Latin over their expositions, to dwell on the details of their manipulations of the female genitalia…” And so the veil of Latin was exchanged for a veil of elision or vagueness.

Veils, like names, may be employed for a variety of purposes. Sometimes people veil a subject to hide it from others; other times, at least in part, so they themselves don’t have to look too closely at it and the ways it refuses to fit itself to their ideas. Lest they have to look too closely at bodies, for example, which tend to insist on their own truths. Names and veils can both be draped over a thing; both can make it harder to see the real outlines of the thing itself.

So much can happen in an unseen space. We’ve learned that again and again. We’re learning it still.

These laughing plagues and dancing plagues, these wandering wombs and Womb-Furies and hysterias and the treatments for them, have been named by men, most of the time. We might make a point of looking closer at what’s behind those names, question more often what frightening or inconvenient things they’re meant to screen, from and for whom. We might wonder, more of the time, what the bodies behind these names might think of the names, if asked. We might actually ask them.

_______________________________________

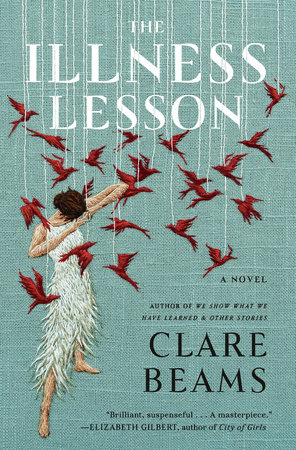

The Illness Lesson, by Clare Beams, is available now from Doubleday.

Clare Beams

Clare Beams is the author of the story collection We Show What We Have Learned, which won the Bard Fiction Prize and was a Kirkus Best Debut of 2016, as well as a finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award, and the Shirley Jackson Award. She has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the Sustainable Arts Foundation. With her husband and two daughters, she lives in Pittsburgh.