“In some sense we derive a profound satisfaction from the loosening of the web of reality; we feel an interest in witnessing the bankruptcy of reality.”

–Bruno Schulz

*Article continues after advertisement

Searching for Schulz

Villa Landau, Drohobych, Ukraine, February 9, 2001

A pair of documentary filmmakers from Hamburg—Benjamin Geissler, thirty-seven, and his stepfather, Christian Geissler, seventy-three—stood in the cheerless stairwell and knocked on the door of apartment 3. They had come in search of Bruno Schulz’s last known artworks, lost for decades behind the Iron Curtain in a three-story building in Drohobych, a town near the Poland-Ukraine border. Built for the Jochman family, the villa had served as a police headquarters before World War II, and as home during the war to Felix Landau. (Before the war the address was 12 Jana Street, afterward 14 Tarnowski Street.)

When the area was absorbed into Soviet Ukraine, Villa Landau, as the building has been known ever since, had been divided into five apartments. Its stern gray walls and steeply gabled roof, unchanged since the war, suggested a fairy-tale castle.

The Geisslers had been brought here not by curiosity but by penance. Christian Geissler was the son of a “convinced Nazi” (in Benjamin Geissler’s description) who died in battle on the eastern front near Poznań in World War II. This heritage weighed on him. Christian titled his first novel The Sins of the Fathers. A committed left-wing Catholic social critic in his youth, he became a Communist in late 1960s, and an anti-imperialist radical leftist who sympathized with the Red Army Faction (RAF), a left-wing terrorist organization, through the 1970s and 1980s.

He began making documentary films in 1969. Benjamin Geissler, born in Ohrbeck in 1964, belonged to a younger generation, the members of which, in the words of Chancellor Helmut Kohl, had “the blessing of late birth.” (Ohrbeck, a town in the German region of Lower Saxony, was the site of a Gestapo-run forced labor camp from January 1944 to April 1945.)

Christian had harbored a fascination with Bruno Schulz since the autumn of 1961, when he read a German edition of Cinnamon Shops. In the spring of 1992, he went to an exhibition of Schulz’s drawings in Munich and learned from the show’s catalog about Bruno Schulz’s lost murals, his last known artworks. In May 1999, he suggested to his stepson that they make a documentary about the murals. “The old man goes from door to door,” he told Benjamin, “and the boy makes a film.” Benjamin Geissler and his wife would later name their son Bruno.

As the past reasserted itself and in its unrushed way let itself be seen again, they were struck mute.The Geisslers made their first trip to Drohobycz in December 2000. After two years of sleuthing, they concluded that the kitchen pantry in a second-floor apartment in Villa Landau had once served as the playroom of Felix Landau’s two children. They approached Schulz’s former student Alfred Schreyer, then seventy-eight, a survivor of the Płaszów and Buchenwald concentration camps. He said that together with his musical talents, the craft skills he’d learned in Schulz’s classes had more than once saved his life in the camps.

Schreyer was the last Jew living in Drohobych born before World War II. “I was born in Drohobycz,” he told an interviewer, “which was a Polish city at the time. I went to a Polish school. Polish was the only language spoken at home. I was brought up in the spirit of Polish patriotism. I always felt, I feel, and I assure you that until the last day of my life, I will feel attached to Polishness.”

Schreyer led the Geisslers to Apolonia Klügler, a former postal worker whose husband, Artek, had studied with Schulz; she, in turn, located Vladimir Protasov, the son of a high-ranking military official, who’d lived in Villa Landau immediately after the war. Protasov disclosed that he had seen Schulz’s murals with his own eyes in the room he had once used as a photographic darkroom. Protasov pointed out the room on a diagram of the apartment.

Two months later, on February 3, 2001, the Geisslers drove their Volkswagen van from Hamburg via Lviv to Drohobych. Christian deliberately took a route past the sites of former concentration camps: Neuengamme, Oranienburg, Gross Rosen, Sosnowiec, Płaszów, and Józefów. On arriving in Drohobych, the Geisslers met up with their Polish sound operator, Marek Sławski, and Jurko Prochasko, their translator and “fixer.”

For Prochasko, a highly educated native of western Ukraine and a practicing psychoanalyst, this was a dream assignment. At age twelve, he had been enraptured by a Polish edition of Schulz’s work on his parents’ bookshelf and taught himself Polish by reading it. During his university studies, Prochasko had come across a Ukrainian translation of some of Schulz’s stories in a literary magazine and found in it a “revelation.”

Nadezhda Kaluzhni, a short, solid woman wearing an apron over a loose house robe with fraying hems, answered the door. Alfred Schreyer introduced himself and Geissler. She peered at the unexpected visitors through thick-lensed glasses and reluctantly admitted them. Her mind was elsewhere: on grieving for her son, who had died a short time earlier, just short of his fiftieth birthday, from a blocked coronary artery, and on caring for her cancer-ridden husband, Nikolai, seventy-nine, confined to his bed.

The elderly couple had lived in the drab apartment for forty-four years. Nikolai was a World War II veteran; he had been conscripted to fight against the Germans near Stalingrad. Originally from Soviet Ukraine, the Kaluzhnis had been resettled here as part of postwar Sovietization. Other than their two daughters, Larissa and Nadia, they were unaccustomed to visitors. Nadezhda became suddenly ashamed of the squalor. “We live like beggars,” she said.

At the mention of Schulz, Nadezhda clasped her knobby fingers tightly over her chest. She told the Geisslers that decades earlier, Polish researchers had searched for Schulz’s murals in vain. “They asked questions, scraped paint off walls, but found nothing.” (In 1965, Poland’s leading Schulz expert, Jerzy Ficowski, had come to this very apartment in search of the murals.) “Nothing,” she said. “They can’t be here. How can they be in this closet?”

Nonetheless, the Geisslers and Schreyer crowded into her narrow pantry (240 centimeters long by 180 centimeters wide, or just under eight feet long by six feet wide), which had a single small window at the far end. In the catacomb-like dimness, their eyes scouted faint but discernible shadows of figures behind shelves swelling with tarnished pots and half-forgotten pickling jars, behind creviced bunches of garlic, beneath smudges of mildew and several layers of pale pink paint. It was as though father and son were practicing muromancy, the obscure art of reading the spots on walls. For a moment, as the past reasserted itself and in its unrushed way let itself be seen again, they were struck mute.

“I can’t see a thing,” Kaluzhni said, wiping her thick glasses. “I can hardly see.” And then, looking again: “Thank God you found it. May God help you.”

“It’s a miracle,” Alfred Schreyer said, his voice trembling with emotion.

Christian Geissler recalled how staggered he was to find Schulz’s images “in the shadows of degradation” (“in den Schatten einer Erniedrigung”). Invoking a line from the poet Paul Celan, “death is a master from Germany,” Christian said he felt as though they were witnessing at that moment an encounter between Schulz and “the master from Germany.”

This wasn’t the first time Schulz’s art had unexpectedly resurfaced. In June 1957, a hitherto unknown drawing of three figures Schulz had made in 1935 was donated to a small private museum in Israel. Nothing was known about the drawing’s provenance except a name and profession stamped on the reverse: Dr. Michał Chajes, Adwokat. It’s not clear when or how Chajes acquired the Schulz drawing, nor why the Drohobycz-born lawyer sent it to Israel, a country he’d never visited.

A parcel containing more than seventy of Schulz’s drawings (and a notebook of sketches Schulz had done at age fifteen, peopled with clowns, imps in top hats, and circus strongmen) resurfaced in 1986. During the war Schulz had entrusted it to Zbigniew Moroń, a math teacher at the Drohobycz high school where Schulz taught. Moroń claimed to have believed that it had been destroyed when Nazis looted his home in 1945. His heirs found it in a timeworn suitcase in Gdańsk, Poland, and arranged for the works to be sold to the Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw.

Finally, Schulz’s only surviving painting, Encounter (1920), had mysteriously appeared at an auction in Łódź, Poland, in March 1992. It, too, was purchased by the Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature.

But of all these discoveries, the reanimation of Schulz’s fairy-tale murals—like Snow White opening her eyes again—would prove by far the most sensational.

*

“As a German”

Drohobych Library, Taras Shevchenko Street, February 16, 2001

Immediately after discovering the murals, Benjamin Geissler alerted Drohobych mayor Oleksy Radziyevsky; Ukraine’s minister of culture, Bohdan Stupka; Poland’s undersecretary of state in the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, Stanisław Żurowski; German secretary of culture Michael Naumann; Schulz expert Jerzy Ficowski; Michael Krüger of Hanser Verlag, publisher of Schulz’s work in Germany; and representatives of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. The immediate response from the latter, according to Geissler: “Listen, who visits Drohobych? But two million people visit Yad Vashem annually.”

“There is no dead matter,” a character says in one of Schulz’s stories.A week after the discovery, on the evening of February 16, Benjamin Geissler convened a confidential meeting at the Drohobycz library—in the very room where Schulz had been obliged to sort books for the Nazi occupiers. On the agenda: how to restore the murals, secure them against theft, compensate the Kaluzhnis, and offer them alternative accommodations. In attendance: Schulz’s former student Alfred Schreyer; three art experts (Agnieszka Kijowska and Wojciech Chmurzyński from Poland, and Boris Voznytsky from Ukraine); the Drohobycz official in charge of cultural affairs, Mikhail Michatz; the Geisslers’ assistant Jurko Prochasko; their translator Roman Dubassevych; and the Polish consul in Lviv, Krzysztof Sawicki. Two decades earlier, Sawicki had written his master’s thesis on Schulz at the Catholic University of Lublin. Now he took a hectoring tone toward Geissler: “As a German,” the consul said, “you have the least rights to this heritage.” An audio recording of the meeting would later be handed over to Ukrainian prosecutors.

*

Pentimento

Villa Landau, Drohobych, February 17, 2001

The next day, February 17, the team of Polish and Ukrainian art experts crammed into the pantry and began the unhurried work of removing layers of paint to reveal Schulz’s brushstrokes beneath. The team included Wojciech Chmurzyński, an expert in Schulz’s art and a former head of the art department at the Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature (where he had curated a major Schulz exhibition in 1992); Boris Voznytsky, a Ukrainian art historian and the director since 1962 of the Lviv Art Gallery; and Agnieszka Kijowska, an art conservator at the National Museum in Warsaw and a specialist in wall paintings.

Kijowska had been part of a team that used advanced techniques (X-ray fluorescence spectrometry and laser ablation) to recover decorations painted between the seventh and fourteenth centuries in churches in Nubia (today’s southern Egypt and northern Sudan). Weeks before coming to Drohobych, she had restored murals in a pharaoh’s crypt in Egypt.

Kijowska lifted her eyes and caught a first glimpse of Schulz’s murals. Dim presences seemed to gather palpability. She beheld a miraculous case of pentimento (the word is derived from the Italian pentirsi, “to repent”), a reappearance in a painting of an original that had been painted over, in this case not by the artist but by other hands.

After a tremulous silence, Kijowska said: Mr. Wojciech….here’s a little face.

Wojciech: Wonderful! Oh my God! It’s typical. Oh my God! Isn’t it? It’s reminiscent of his self-portraits. Oh my God!

[Kijowska laughed in delight.]

Wojciech: This is it!

“There is no dead matter,” a character says in one of Schulz’s stories; “lifelessness is only an external appearance behind which unknown forms of life are hiding.”

That same day, news of the rediscovered murals, leaked by Sawicki, appeared on the front page of the Polish right-wing daily Life (Życie). According to Jurko, Nadezhda Kaluzhni had said, “I’m at the end of my days. Just promise me this will remain quiet.” Benjamin Geissler had given his assurances. Betraying Geissler’s trust, Sawicki had taken the liberty of informing the press, and journalists were soon swarming outside the Kaluzhnis’ door.

“This flat was privatized, it’s our property, we can do what we want,” Nadezhda Kaluzhni told the Guardian. “No one told us these paintings were valuable. They’re not even paintings, just smears on the wall. It would be different if they were frescoes, Italian, Michelangelo or something.”

“We knew about this house’s past,” Nadezhda told another reporter, “about that Gestapo monster [Felix Landau] shooting people from the balcony, but who could have imagined we’d never get any peace thanks to some old smears on the wall?” Her husband, Nikolai, threatened to “take an ax” to the remaining murals in his apartment, if he and his wife were not given “inviolable” peace from reporters.

*

A Museum in the Executioner’s House?

Drohobych Town Hall, February 19, 2001

Benjamin Geissler sensed that some were prepared to go to great lengths to get those “old smears.” He wrote a letter to the mayor, Oleksy Radziyevsky, to assert copyright over images of the murals and to implore the mayor to prevent anyone not authorized by the expert team, especially television crews, from entering the Kaluzhnis’ apartment.

On February 19, Geissler met the mayor at the town hall to deliver the letter in person. He was joined by Christian Geissler, Alfred Schreyer, Mikhail Michatz, and deputy mayor Taras Metyk. The mayor told the Geisslers:

The Drohobych city council welcomes the filming of your documentary “Finding Pictures.” We are particularly happy about the first results: the discovery of the murals of the world-famous writer and painter Bruno Schulz from our city. Since the end of the war, many experts have searched for this unique work of art. We hope to have a good cooperation with you. We are thinking on the one hand of the successful progress of your shooting, but on the other hand also of building a memorial for Bruno Schulz in the former Villa Landau. Since there are no funds for such a measure in the city budget, we ask you to work internationally to raise such funds.

Finally, the mayor gave assurances that Schulz’s murals would be protected in situ and suggested having the room containing the murals sealed for reasons of security. Benjamin Geissler replied that since the Kaluzhni family still used the room as a pantry, sealing it wouldn’t be right.

The next day, the Geisslers returned to Hamburg via Kraków (where they reported their discovery to leading Schulz scholar Jerzy Jarzebski). On returning home, Benjamin Geissler began to look for funding to relocate the inhabitants of Villa Landau and to repurpose the building as the Reunion and Reconciliation Center and Bruno Schulz Memorial Museum. “Not just a museum,” Geissler said, “but also a place of encounter. For contemplating, talking, and being silent.”

The competing claims that arose so long after Schulz’s death are like the ends of separate strings that trace their origins back into Schulz’s life.To inquire about funding, he called Matthias Buth, a senior official at the Federal Commissioner for Culture and Media Affairs (Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien) in Bonn. Buth replied that while the German government recognized a moral obligation to help, it could act only if it received official requests from Ukraine and Poland, preferably at the ministerial level. Geissler next approached Joseph H. Domberger, a real estate entrepreneur in Munich and honorary president of B’nai B’rith Europe, who offered to help underwrite the proposed Schulz museum. Domberger was born in Drohobycz in 1926 and lived there until age thirteen. Geissler asked Boris Voznytsky to meet the prospective donor in Drohobych in early June.

On February 23, Geissler contacted the German industrialist Berthold Beitz, then eighty-seven, a former adviser to Konrad Adenauer and then head of the Krupp Foundation, a major German philanthropy based at Villa Hügel in Essen. “Beitz was initially very interested,” Geissler told me. Geissler knew of Beitz’s personal interest in the matter. During the German occupation, he had been assigned to supervise the Carpathian Oil Company in Borysław, the town adjacent to Drohobycz. In August 1942, Beitz had saved 250 Jewish men and women from a transport train to the Belzec extermination camp by declaring them essential “petroleum technicians.” He also gave local Jews advance warnings of Nazi roundups, issued and signed fake work permits, and, together with his wife, Else, hid Jews in his home.

Władysław Panas, a prominent Schulzologist from Lublin, objected that establishing a Schulz museum in “the executioner’s house” would be in bad taste. But according to Anne Webber, a representative of the European Council of Jewish Communities and the Commission for Looted Art in Europe, “the planned museum would have provided an ideal opportunity to strengthen awareness in the Ukraine and beyond of what befell the Jewish people and would have helped build relations between Jews and the local communities.” “Schulz is for us an iconic cult figure,” said Andriy Pavlyshyn, a Ukrainian translator of Schulz and the editor of a cultural journal in Lviv:

That is why everything that is happening in Drohobych is very important for us emotionally. . . . From the first step Benjamin Geissler took here, his position was: to act legally, in coordination with all stakeholders, and in such a way as to bring the greatest benefit to the Ukrainian people and our international image. . . . The plan was that after the restoration of the murals, they would create a museum in Drohobych, the birthplace of Schulz . . . the homeland of the great Mitteleuropa culture, to which we, Ukrainians, belong as an essential element! But this museum should be not a dead collection of images or artifacts but a place of living communication, a center of unity, where the people of Drohobych could learn more about the wider world, and people from abroad could learn more about Drohobych.

Several months before the discovery, Jerzy Jarzebski, the author of the introduction to the standard Polish National Library edition of Schulz’s works and the co-editor of the four-hundred page Schulz dictionary, had lectured at the Hebrew University on Polish literature (including Schulz). He told me how the museum was envisioned:

Maybe it was naïve, but our intentions were the best. The paintings were to play a very important role in this, as the only works by Schulz whose fate was not thrown beyond Drohobych. As our Ukrainian hosts made me the chairman of the Scientific Council of the Schulz Museum, I initially designed this museum not so much as a repository of the writer’s memorabilia but, rather, as a study center for which the area of activity would be the entire Drohobych, its “Schulz sites,” and in the very core of it the paintings. . . . All this on condition that the fairy tales would not be torn off the wall and taken to another country.

Which is precisely what was about to happen.

Bruno Schulz once wrote: “The knot the soul got itself tied up in is not a false one that comes undone when you pull the ends. On the contrary, it draws tighter. We handle it, trace the path of the separate threads, look for the end of the string, and out of these manipulations comes art.” The competing claims that arose so long after Schulz’s death are like the ends of separate strings that trace their origins back into Schulz’s life.

__________________________________

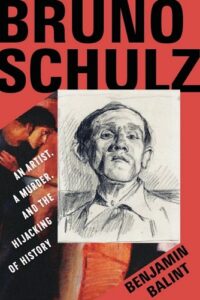

Excerpted from Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History by Benjamin Balint. Copyright © 2023. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.