I’d taken to calling my father güey, a term that evolved from the word buey, Spanish for ox. Originally, the term buey was used to refer to the husband of an unfaithful wife. The horns of the bull were emblematic of the wife’s adultery and were said to loom over the head of the woeful husband, who, unlike those around him, was unable to see the horns, just like he was unable to see that his wife was tumbling in the hills with another man. Thus the townspeople of an older Mexico grew fond of making the cruel remarks: “Le pusieron los cuernos” and “Lo hicieron buey,” whenever they came across a man afflicted by the calamity of having an adulterous beloved.

The closest we have to this in English is the term cuckold, which finds its origins in the Old French word for cuckoo: cocu. The female of this bird—the cuckoo—was known for laying its eggs in the nests of other birds and gained the reputation of being unfaithful to her mate. Consequently, the French of the Old World would say that the husband of a straying wife was cucuault. Later the term would make its way into Middle English as cokewold. In “The Miller’s Tale” in The Canterbury Tales, for example, Chaucer writes: “Who hath no wyf, he is no cokewold.” And though cuckoos do not have horns, horns have always been associated with cuckoldry. Thus the cuckolded man is no different than el buey who walks around with horns he cannot see looming over his head.

But I digress. Because my father was no buey and he was no cuckold. He was in fact, just a güey: a fool, a ridiculous man. This, in its simplest form, is what güey has come to mean. Among the more lowly folk of Mexico, güey is often used as a less-than-formal term of address. In English you might hear someone, most likely a male teen, refer to his friend as fool. “Hey, fool!” he might call out to his comrade insouciantly, without malice; and in turn the comrade might respond: “What’s up, fool. What troubles thee?” There is no harm in such a greeting. The same goes with the word güey. But like the word fool, which can also be used to insult someone, so too can the word güey. And because of this, güey is a term that a son should never use to address his beloved papá.

*

I was ten when I first referred to my father as güey. It happened during one of those summers when my mother would send me to Chihuahua for my vacation. I’d been spending the day with my tíos José, Chuy, and Juanito (three of my mother’s four brothers) at their home watching them build a brick wall around the backyard. Around midday, when they took a break for lunch, I joined them for bean burritos and Cokes on the front stoop of the house. My tíos were cool, real suave dudes. As they munched they tossed around jokes and stories about adventure and female conquest, more specifically about the neighbors’ two daughters, a couple of pale and homely looking Mennonites with whom the three claimed to have had their way at one time or another, each claiming to have taken the virginity of one of the girls at some point.

Even I, at my young age, was intelligent enough to realize that one of them had to be lying since there were only two girls and three of them. But each swore that it was he who’d done the deed, who’d slimed the panties of one of these otherwise virtuous creatures who lived by the word of God. None, however, on account of the girls being twins, could say with certainty which girl he had in fact devirginized, which in a way worked to defuse the argument. Whatever the case, and regardless of who’d been telling the truth and who’d been lying, talking about these girls made them laugh and giggle and slap hands. With less enthusiasm and fewer body gestures, they also talked about how they were progressing in their work building the wall.

There were times when they’d point to what was great about the wall and times when they’d point to what was not so great about it and shake their heads in disappointment. Other times they’d bring me into the discussion and ask what I thought about the wall and about the neighbors’ daughters. They’d mostly laugh and go wild over the magnificent shit I said. This made me feel like I fit right in with them—real cool, like I was a real suave dude, too. And every time they referred to a male in one of their jokes or stories, they used the term güey. They threw it around like bolo at a Mexican wedding. Sometimes they’d even address one another as güey.

I wanted to get away from the awful sin I’d committed against the man who loved me unconditionally.

This being the case, and me being the naive and wickedly amenable little gamin that I was, I began to softly utter the word beneath my breath and quickly took to liking it. It tasted something fresh on my tongue, new. And the more I uttered it, the more I grew in spirit and manhood. I could feel my little balls growing and I couldn’t wait to use the word freely, out in the open, in front of my tíos. I’d be great in their eyes. They’d get a real kick out of hearing the word shooting forth from my sloppy mouth: “What a great kid this kid; he catches on quick; he’s just like us.” I imagined them giving me manly nudges on my chest and chin and high-fiving me. The scene played out in my head as concretely as the brick wall that was taking form before us.

It didn’t take long for the perfect opportunity to present itself. My tío José, who has always been of a devilish mind, and who’d been sitting the farthest from me on a pile of red bricks and cement sacks, asked me: “Obed, no extranas a tu papá?” to which I gaudily replied: “And why would I miss that güey?” I’d done it! I’d shot the word right out of my bean burrito–filled mouth and into the dry Chihuahua air for my three suave tíos to hear. Without a snag my “güey” made its way right into their powdered-cement-dust-filled ears like red jalapeno peppers up their culos, causing them to let out a collective explosion of cacophonous laughter.

Confused, chaotic shrieks came from their mouths as they clutched their pansas and kicked out their feet like fighting cocks. I didn’t feel like that suave little vato I’d been earlier when they’d laughed at my silly wisdom. Instead, a sharp shiver shot up my spine, paralyzing me with ache and fear. The sound was ugly. It pounded in my brain like the bells of Notre-Dame in the brain of Quasimodo. Suddenly, I wanted my tíos to stop, to shut their mouths and swallow their laughter, which felt like a big hand gripping my neck and cutting off my air. I wanted everything to go back to the way things were only moments earlier. Suddenly, from some feet behind me, I heard a voice say: “Qué onda, hijo? Why do you call me güey? Soy tu papá.” His words met my heart with the crashing force of a bowling ball hitting the floor. I immediately realized my mistake, my childish blunder.

My innocence had been taken for a ride and I’d walked right into the trap these three Lady Macbeths had set for me. Even if my tío José had not been expecting me to call my father güey, he had been expecting me to say that I didn’t miss him, my father, who everyone but I had noticed was making his way to our circle, and this would have hurt nonetheless—even if not as much as hearing me call him güey. And now, feeling small and alone, I didn’t know what to do. All I knew was that I had to turn to face my father. And when I did, he was already wrapping his arms around my paralyzed body; his lips were already finding a place at the base of my forehead, providing me with the sense of security for which, at that moment, my whole being had been desperately yearning.

Meanwhile, my tíos kept laughing crazily. And it hurt. I felt it choking me. And I wanted to get away from the awful sin I’d committed against the man who loved me unconditionally. I didn’t know what to say to him, and by the way he pressed me against his body to protect me from my culeros tíos’ awful laughter, I could sense that my father didn’t expect me to say anything. In the security of his arms, with my ear listening to the heavy beat of his heart, I felt like a little culero myself, and small, very, very small. I’d called my father güey practically to his face, offending his paternal spirit. And still, my father offered me a smile and his arms. I didn’t mean it, Papá, really, I didn’t, I wanted to say to him. I don’t even know what the stupid word means.

__________________________________________________________________

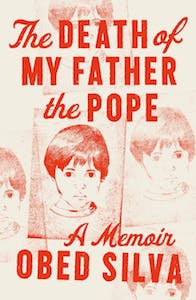

Excerpted from The Death of My Father the Pope by Obed Silva. Published by MCD, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Obed Silva. All rights reserved.

Obed Silva

Obed Silva was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, and immigrated to the United States as a toddler. After years in the gang lifestyle—which left him paralyzed from the waist down, the result of a gunshot wound—he discovered the power of book learning, earned a master’s degree in medieval literature, and is now a respected English professor at East Los Angeles College. The Death of My Father the Pope is his first book.