When I was in eighth grade my sister helped kill another girl. She was in love, my mother said, like it was an excuse. She didn’t know what she was doing. I had never been in love then, not really, so I didn’t know what my mother meant, but I do now.

This was in Ashaway, Rhode Island, outside Westerly, down along the shore. That fall we lived in a house by the river, across the road from the mill where my grandmother had met my grandfather. The Line & Twine was closed, posted with rusty

NO TRESPASSING signs, but just above the dam someone had snipped a hole in the fence with bolt cutters so you could sneak in the back. We used to roller-skate up and down the aisles between the dusty looms, Angel weaving, teaching me how to do crossovers and go backwards. She could do spins like an iceskater, her hands making shapes in the air. I wanted to do spins and be graceful like her, but I was chubby and a klutz and when

I stood beside her in church I was invisible. My mother said I shouldn’t worry, that in time I’d find my special talent. “I was a late bloomer,” she said, as if that was supposed to be comforting. What if I didn’t have a special talent? I wanted to ask. What if a

hopeless nerd was all I’d ever be?

My mother’s talent was finding new boyfriends and new places for us to live. She worked as a nurse’s aide at the Elms, an old folks’ home in Westerly where my great-aunt Mildred lived, and didn’t make any money. Fridays she’d come home and change, brushing her hair out, making up her face, using too much perfume. She’d been a cheerleader and could dance. She dieted, or tried to. Facing the narrow mirror on her closet, she complained that nothing fit her anymore. I used to look like you, she told Angel, like a threat, and it was true, in her old pictures they could have been twins. If she’d wanted to, she said, she could have married a doctor, but they were all assholes. Your father was sweet.

We knew our father was sweet. What we didn’t understand was when he’d become an asshole, or why. My grandmother had never liked him because his family was Portuguese. He’d tricked my mother into turning Catholic and then abandoned her. Never trust a Port-a-gees, she said, like it was a joke. I had his dark hair and eyes, so what did that make me?

My mother’s boyfriends tried to be sweet, but they were strangers. Sometimes they paid our rent and sometimes we split it. When they broke up with my mother—suddenly, drunkenly, their shouting jerking us from sleep—we would have to move again. Like her, we were always rooting for things to work out, far beyond where we should have. Our father was gone, and our mother couldn’t stop wanting to be in love. “I swear this is the last time,” she’d say, dead sober, and a month later she’d bring home another loser. They seemed to be getting younger and scruffier, which Angel thought was a bad sign. My mother didn’t seem to notice. In the beginning, everything was new. She lost weight and kissed us too much and made promises she couldn’t keep. The last had been a deckhand named Wes who brought home lobsters and called her “Care” and took us to Block Island to ride bikes, until one night he smashed her phone when she

tried to call the cops on him. Neither of them was bleeding, so the cops didn’t charge anyone. “You guys are useless,” my mother said. “Yeah,” one of them said, “that’s why we’re here at one in the morning, cause we got nothing better to do.” We were living

in the top half of a duplex, and the next morning while Wes was out dragging the Sound, the three of us lugged everything we could carry down the stairs and shoved it in my mother’s car.

The house by the Line & Twine was for sale, but in 2009 no one was going to buy it. My grandmother had worked in accounting with the owners, snowbirds who’d shipped off to Florida long before the Crash. Like most of the houses on River Road, it had been sitting empty for years. There was moss on the shingles and weeds in the gutters.

My grandmother came over to help us clean the kitchen. She brought her rubber gloves. “It’s not the Taj Mahal,” she said.

“It’s fine,” my mother said, as if we wouldn’t be there long.

“Angel Lynn. Quit with the face.”

“I didn’t say anything,” she said, scowling.

“You don’t have to.”

I didn’t say anything. I hardly ever said anything, afraid of making things worse. I watched them like a scorekeeper, silently recording every slight and insult, every failure to be kind. I was thirteen, and like all children, had an overdeveloped sense of

justice. I wanted everyone to be happy, despite our actual lives.

At the duplex, Angel and I had shared a bedroom. Here we each had our own, our doors closed. Lying in bed, I missed her texting with her friends long after I’d stopped reading, the glow on her face as she concentrated soothing as a nightlight. My secret wish was that when I started high school I would magically turn into her, that I would inherit her powers, not just her looks and toughness but the confidence that attracted people to her, the knowledge that no matter what, she would always be wanted. Now, without her, in the dark, with the road silent and the river spilling over the dam behind the Line & Twine, that dream seemed even more unreachable.

Our father hadn’t completely abandoned us. He still came by to do repairs like fixing the doorbell or snaking the shower drain, a constant problem with our long hair. He had us every second weekend, taking us surfcasting, letting us drive his truck on the

beach. The summer people were gone, the mansions where he did landscaping shuttered for the season, their spiked iron gates chained. The clam shacks and Del’s Lemonade stands were closed, and we’d end up in town for lunch at One Fish Two Fish, a grease pit in an old Burger King where we’d gone when we were little. It still had the original bright yellow-and-orange Formica booths, the tabletops chipped and dirty at the edges, every stray grain of salt visible. We didn’t have a lot to say to one another, as if we were afraid of giving away secrets that might be used against us. We talked about school mostly, and Angel’s job at CVS. He had an apartment in Pawcatuck over a Chinese restaurant, the whole place saturated with the smell of burnt cooking oil. He had to move the heavy sea chest he used as a coffee table to set up the pullout couch from Bob’s he’d bought just for us, the same faded Little Mermaid sheets every time, though we’d long outgrown Ariel. Sunday, while my mother and grandmother were at church, we slept late and he made us waffles, another leftover from our childhood, before delivering us home. In our driveway, letting us out, he gave us each a twenty, as if tipping us. For our mother, sometimes he had a check and sometimes he didn’t, depending on how business was. They fought bitterly over money, which embarrassed us, and it was a good weekend when he had the full payment. I stayed on the porch to wave him away while our mother and Angel went inside.

“How was it?” our mother asked. “What did you all do?”

“Nothing,” we said. “The usual.”

She wasn’t really interested, and we were already searching for clues to what she’d done with her weekend, sniffing the air for any hint of weed or body spray, checking the ashtrays for Marlboro butts, the recycling bin for extra beer bottles.

One Sunday, Angel found the foil corner of a condom wrapper under our mother’s nightstand. She showed it to me on the palm of her hand like evidence.

“So what?” I pretended I wasn’t frightened by the idea of another stranger taking over our home.

“So she’s fucking someone.”

“Der.”

“She was probably fucking drunk. She probably didn’t even know the guy. I’m so grossed out right now. She’s such a fucking skank.”

I wanted to defend our mother. She was lonely and didn’t know what else to do. “At least he’s not still here.”

“Just wait,” Angel said, and she was right.

The next Friday our mother warned us that Russ was coming to pick her up. He was a fireman but also had a landscaping business. We expected him to have a truck like our father, but the car that pulled up was a little silver Honda like our grandmother’s. Russ was shorter than our mother, and bald, with thick bifocals and a salt-and-pepper beard and a gut that stuck out over his belt. Instead of skinny jeans and motorcycle boots, he wore forest-green corduroys and brown loafers. He had a chunky class ring, and shook our hands limply, like Reverend Ochs after church. Our mother made a point of saying they were going out to dinner, then to a movie at the Stonington Regal, as if they hadn’t met at a bar.

“Weird,” Angel said as we watched them drive off.

“Yeah.”

“He’s like Papa Smurf.”

“That’s mean,” I said.

“Oh Carol, I want to put my smurf in your smurf. I’m going to smurf you all smurf smurf.”

I slapped her on the shoulder and we laughed, bumping into each other like teammates.

“Oh my God,” she said. “What if he’s the one?”

“Stop.”

“It’s sad, actually. It’s like she’s giving up.”

“He’s not that bad,” I said, because I thought she was still joking, but when I looked at her she was wiping away tears.

“Ange, come on.”

She turned her back so I wouldn’t see and reached for a tissue, blew. She hated to cry, thinking it made her weak, but she cried all the time. “It’s so fucked-up. She’s just going to make it worse. You make a mistake, you fix it, you don’t make it again, you know?”

“Yeah,” I said, but I was too frightened to admit I didn’t know what we were talking about anymore. Her boyfriend Myles, I guessed, because normally Angel would be with him, the two of them cocooned in their own little world. By the time

I realized what she meant, it was too late.

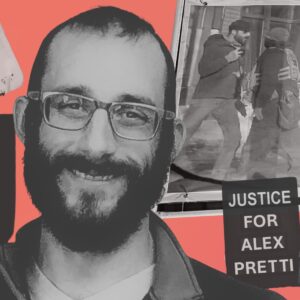

The girl my sister helped kill was named Birdy Alves. On the news they called her Beatriz, but everyone at school called her Birdy. She played soccer and softball and worked at the D’Angelo on Granite Street. She was petite, with big eyes and a heart-shaped face. Like Angel, she was popular, but she was from Hopkinton, a totally different clique.

Right around Halloween, Birdy Alves disappeared. For weeks the whole state was looking for her. Every night we’d see her face on the Providence news. If you have any information, they said, please call the Hopkinton police.

I loved my sister. I didn’t want to believe she’d lie to me. Even now I want to believe she was trying to tell the truth that night our mother went out with Russ the firefighter, to warn me not to be like her. She might have. Nothing had happened yet.

Later the police would put dates to everything, but for now we were two girls alone in a house on a Friday night with nowhere to go. We made popcorn and snuggled under an afghan on the couch with the lights out and watched Mystic Pizza, one of my mother’s favorites, trading the bowl back and forth, our feet in each other’s laps. She was Julia Roberts, I was Lili Taylor. It didn’t matter that half the time she was on her phone. We didn’t have to speak. All I wanted was to be close to her like this, the two of us laughing at the same places. She was the only one who knew what we’d both been through, and I liked to think we were inseparable, bound by more than just blood. We weren’t happy

that fall, in that rotting, underwater house, with everything we’d already lost, and everything still to come, but lying safe and warm under my grandmother’s afghan, eating popcorn and stealing glances at my funny, beautiful sister as the light played over her face, I wished we could stay there forever.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Ocean State. © 2022 Stewart O’Nan. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.