The Ocean is a Lesbian: Notes on Queer Women and Water

"What is it with these lesbians and why are they all so wet?"

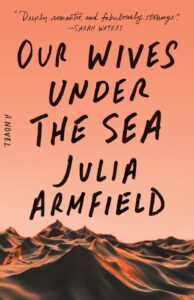

I’ve been thinking about lesbians and the water lately, which is very fashionable of me. It’s a combination of topics enjoying a moment in film and in literature; queer women cast out upon the ocean, struggling up from the shallow ends of swimming pools. In doing the promotion rounds for my novel, Our Wives Under the Sea (which has been out in the UK since March), a not inconsiderable number of people have taken the time at events and in interviews to ask me essentially the same question, vis: what is it with these lesbians and why are they all so wet?

The motif is one that twists its way through a number of contemporary queer classics, from the oceans and pools of Céline Sciamma’s coming-of-age trilogy to the boats that skim across the surface of Hannah Kent’s novel Devotion, Kirsty Logan’s The Gracekeepers and Lauren Hadaway’s gorgeous, punishing debut feature The Novice. It is a theme that perhaps has come to self-perpetuate; the synonymity of queerness and the water taking on a sense of something given, a combination that speaks for itself. The moon is a lesbian, goes the meme, and since her gravitational pull exerts such influence on the tides, it stands to reason that the ocean is a lesbian too.

Our Wives Under the Sea is a novel about the water, or rather the fact of returning from it. Concerning a married couple, Miri and Leah, it tells the story of marine biologist Leah’s return from a routine submarine expedition which appears to have gone horribly wrong and her wife Miri’s uneasy conviction that things are not as they should be. In writing the novel, I became increasingly aware of the contradictions of the water and the differing moods and colors it offered as it came to augment the plot.

On the one hand, particularly regarding Leah and the novel’s central mystery, the ocean stood for the unknown and crushing pressure, but it also came to stand in for freedom, for adventure and the beginning of love; the waves which lap against one’s feet and promise a pleasant kind of drowning. A recurring image concerns Miri’s recollection of Leah teaching her to swim—the way she held me round the waist at the Lido and told me to kick, told me that she would buoy me along—and I think it was this duality of safety and threat, of floating and of sinking, which came to be central to the novel and, more generally, to the way I read the water in other queer and lesbian media.

From a storytelling perspective, the ocean can give a narrative its heartbeat. The crashing waves that soundtrack Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire and Francis Lee’s Ammonite bleed into the rhythms of these movies and lend their central romances a sense of almost tidal inevitability. The effortful swimming of protagonist Julie in Sara Jaffe’s surly and sublime novel Dryland likewise beats a rhythm against which the flirtation, infatuation and concerted not-coming-out at the story’s core seems to struggle.

In The Novice, Isabelle Fuhrman’s obsessive sculling provides the movie with its painful, hammering pulse; a destructive beat against which the movie’s central queer relationship is ultimately scuttled. In each case, the water offers a sense of the inexorable, of something larger than the characters who spend their stories submerged, treading water or waiting to jump.

Come on in, the water’s lovely.

The metaphorical nature of the water lends itself to a number of different aspects of queer storytelling, fulfilling different roles as required. It can serve as a visual reminder that two things can simultaneously be true—a theme explored to great effect in Sciamma’s 2007 movie Water Lilies, in which the rigid femininity of the synchronized swimming that takes places on the surface of a pool contrasts with the furious activity required beneath. It is an image that speaks eloquently to the queer sensation of being known and not being known, to the energy required to retain a facade of acceptable womanhood.

Sciamma warms to this theme of duality in Portrait of a Lady of Fire, a movie which connects its central lovers to the ocean at almost every opportunity. Almost our very first image of Noémie Merlant’s artist Marianne shows her diving from a rowboat to rescue her canvases from the water. She arrives, Viola-like, on an unfamiliar shore, bound to meet a luminous Adèle Haenel as Héloïse, the subject of her secret assignment.

What follows is a romance in which Marianne and Héloïse are both one thing and another, women of their period and women in love, Marianne masquerading as a companion and painting Héloïse in secret, all ringed around by water. It is an ocean which represents both beauty and danger, the façade of the surface and the chaos of love beneath. Héloïse flirts with the notion of the water, at one point breaking into a run near the cliffedge but stopping before she goes over. “I’ve dreamt of doing that for years,” she says. “Dying?” Marianne asks and Heloise responds, “Running.”

It is a scene we will recall later when Héloïse finally decides to walk into the ocean, letting Marianne watch her figure out whether or not she can swim. The ocean, here, is something to be feared but also something to long for—much like love and the panic of love.

The water often represents the duality of expression that can be necessary to queerness but it also works as the bearer of a kind of fundamental truth. In a number of queer novels, the water works as a catalyst for coming out or coming into oneself. In Mary McCarthy’s The Group (no spoilers, but come and talk to me if you know), a crucial fact of queerness stems from the act of crossing an ocean and coming back again.

Likewise, the pools and oceans of Dryland, Kirsty Logan’s The Gloaming and Sarah McCarry’s About A Girl function as a kind of baptism; bodies of water to be crossed or entered in order to become more fully oneself. This sense of truth, of coming out and its curious entanglement with the sea and the water, is really all over the place when you look for it, from the seaside setting of Tipping the Velvet to the 2004 movie My Summer of Love, and even in flawed urtexts like Channel 4’s Sugar Rush.

But it is a fact that can and should be properly situated in history. After all, the theme may well self-perpetuate and repeat itself because of fashion but it is also embedded in an older and more foundational sense of community, in the history of cruising and transgression in public spaces, in the key roles the ponds and the oceans have played to decades of queers. The history of Fire Island as a cruising space for men is well-documented, but in her essay Lesbian Memories 1: Riis Park, 1960 (anthologised in A Restricted Country: Essays & Short Stories), Joan Nestle recalls the crucial role played by hot weekends by the ocean:

I knew that at the end of that residential hegemony was the ocean I loved to dive into, that I watched turn purple in the late afternoon sun, that made me feel clean and young and strong, ready for a night of loving, my skin living with salt, clean enough for my lover’s tongue, my body reaching to give to my lover’s hands the fullness I had been given by the sea.

In Our Wives Under the Sea, Miri reflects on a memory of Leah taking her to the beach to witness a sea lung: a semi-mythological ocean phenomenon in which the air changes temperature rapidly enough to freeze water thrown to the surface in choppy weather. The effect created is that of both give and solidity, the ice forming a floating platform on top of an otherwise unchanged sea. It is an image I used to invoke a sensation of one thing and another, a sight that Miri looks upon with fascination:

I pressed my free hand to my chest and wondered how solid that could really be, how tangible anything about me might really be. Standing on the edge, I could feel it. The chill of the air, aching to become something else.

Looking back on the image now, I think (or I hope) it also works to illustrate the plurality of the queer experience—the way it can require us to be different things to different people. Miri is one thing to her difficult mother, another to her straight friends, another thing altogether with her wife. The ocean, in Our Wives, is a lot of things but crucially it is a prism through which the queer women at the core of the story are refracted. I think that the metaphorical flooding of so much of queer media often works like this: plunging its women in water to bring them up altered, complicated, difficult and somehow more fully themselves.

So come on in, the water’s lovely.

__________________________________

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield is available via Flatiron Books.

Julia Armfield

Julia Armfield is the author of the story collection salt slow and the novel Our Wives Under the Sea. Her work has been published in Granta, Lighthouse, Analog Magazine, Neon Magazine, and Best British Short Stories. She is the winner of the White Review Short Story Prize and a Pushcart Prize, and she was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award in 2019. She lives and works in London.