Obeying the Undeniable Call of Iceland

Roni Horn on the Landscape That Won't Let Her Go

My first venture abroad was Iceland. It was 1975 and I was nineteen. My memory of the trip is dominated by weather. The sky, the wind, and the light all made a strong impression. Weather simply hadn’t occurred to me before then.

In 1978 I received a grant from graduate school. I used it to return to Iceland the following year. For six months I roamed the island. With a dirt bike modified for long distance travel, I was portable; I lived in a tent furnished with candles, sleeping bag, and cook stove, pitching camp wherever I tired.

It was a solitary journey. The roads were unpaved. The bike was well suited; with no limits on access, I went everywhere. The distinction between public and private hardly existed then, and never restricted direction. Anywhere was possible.

Except for short interludes, I was outside 24/7, exposed to the inclement weather, the riotous force of the wind, and the loud whining of the two-stroke engine. The roads, not fit for distance, made travel demanding and slow. That spring and summer, the seasons of my journey, were claimed as the coldest and wettest in the island’s recorded meteorological history. With no grading the dirt roads hugged the natural contour of the landscape. The local ups and downs greatly slowed horizontal progress. With distance attenuated in this manner, arrival lingered endlessly off in the distance.

I returned to Iceland with migratory insistence and regularity. The necessity of it was part of me. Iceland was the only place I went without cause, just to be there.

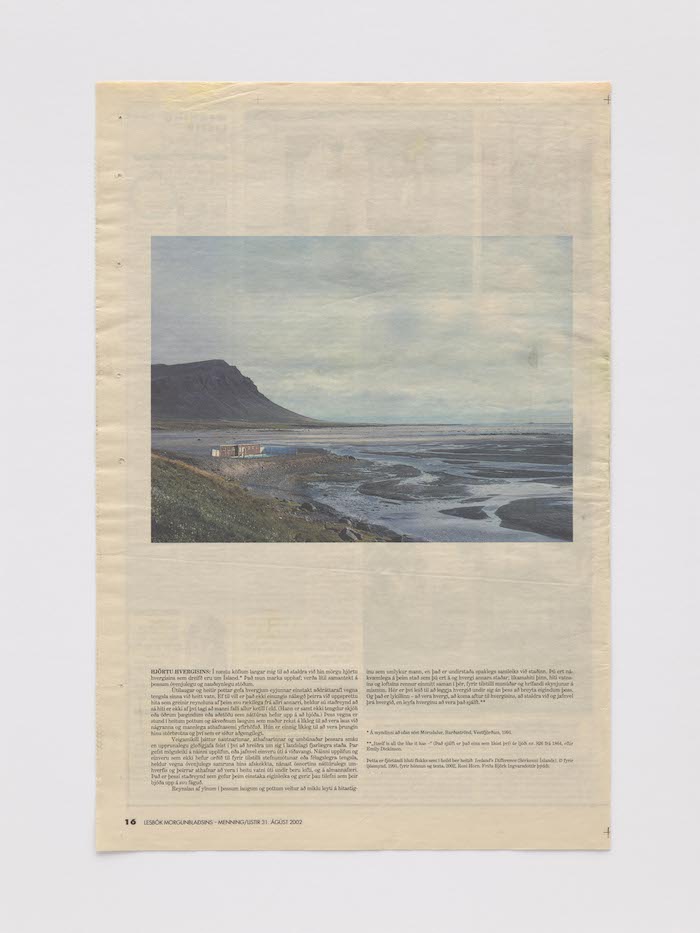

From Iceland’s Difference, 2002-3. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth: Ron Amstutz, New York.

From Iceland’s Difference, 2002-3. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth: Ron Amstutz, New York.

Early on I imagined compiling an inventory of rocks and geologic debris. Each rock was that compelling. Travel was crowded with attention-grabbing views and weird organic formations. To date there is no inventory, only the dream, though I remember them. I remember the rocks.

I recall the first image I associated with Iceland from childhood. It was that of a horizonless ocean at the center of the earth.

In 1982 the national chief of lighthouse keepers gave me permission to stay in a lighthouse off the southern coast. For six weeks I lived up on the bluff at Dyrhólaey. The building, from the early part of the twentieth century, included living quarters. But when the light was automated the lighthouse went uninhabited for decades.

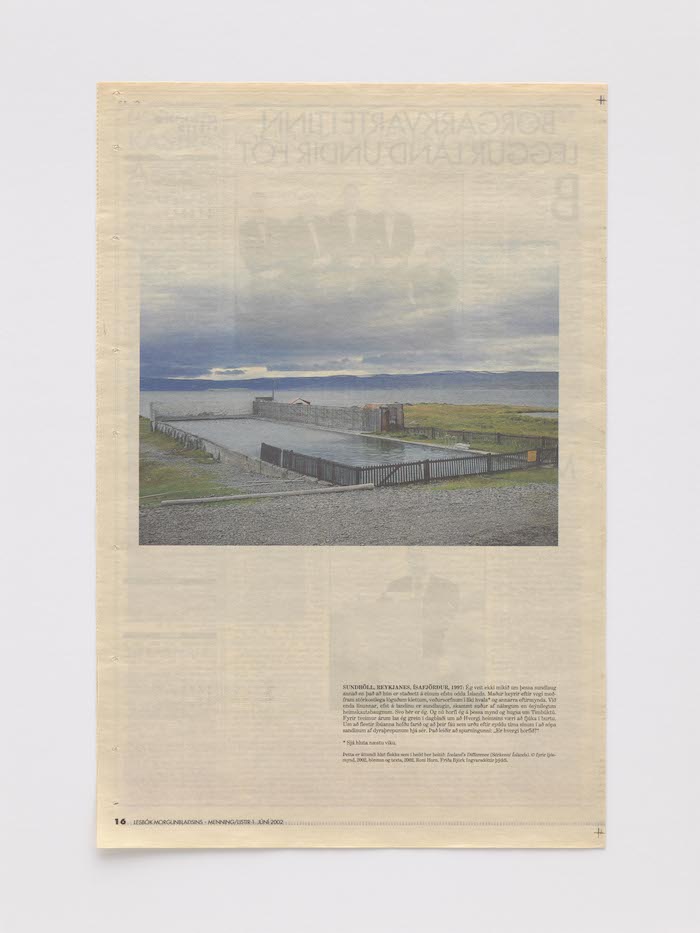

From Iceland’s Difference, 2002-3. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth: Ron Amstutz, New York.

From Iceland’s Difference, 2002-3. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth: Ron Amstutz, New York.

I arrived in early May. And since I wasn’t going anywhere, it soon began to feel like an act of submergence—going deep but not going far. Staying put among local change was travel. The bluff was action packed. It was a matter of attention. Between the water and the light, the birdsong and the wind, the rocks and the weather. Between the sand and the seals and the eider and the puffin, I was busy.

In the mid-1980s I began work on To Place: a series of books—an encyclopedia of sorts, based in what would become a lifelong relationship to the island. The first volume, Bluff Life, was published in 1990. Currently it is ten volumes deep.* I’m not anticipating an end to it since I’ve discovered, paradoxically, that To Place becomes less complete with each new volume.

By the early 1990s Iceland had become quarry and source. At times travel seemed closer to hunting or mining. Extraction, I thought, was the basic act. The drawings, sculpture, and photographic work I was producing at the time integrated the presence of the island and the experience it offered. But as I view the dynamic now, the reality was quite different: Iceland was a force, a force that had taken possession of me.

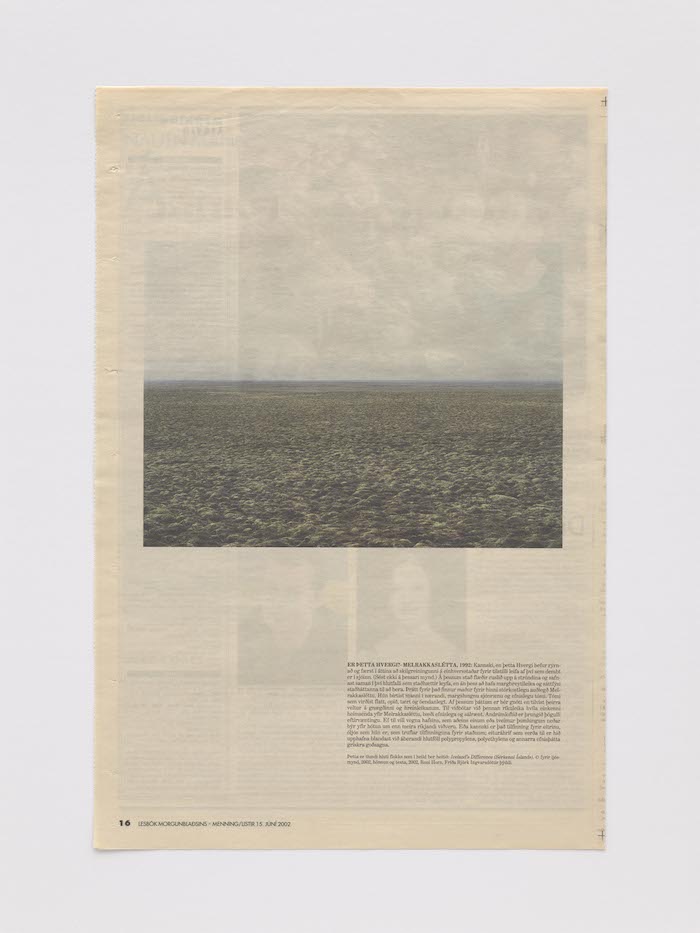

From Iceland’s Difference, 2002-3. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth: Ron Amstutz, New York.

From Iceland’s Difference, 2002-3. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth: Ron Amstutz, New York.

*

I recall the first image I associated with Iceland from childhood. It was that of a horizonless ocean at the center of the earth. I knew it was Iceland because Jules Verne had decided, discovered, or determined that the entrance to the center of the earth was located there. With all the years and all my travels, the truth of this insight has only deepened.

I’m often asked but have no idea why I chose Iceland, why I first started going, why I still go. In truth I believe Iceland chose me:

The island.

The ocean surround.

The going north.

The light.

The emptiness.

The full-up vacancy.

The wholeness.

The absence of parts.

The wholeness of something entire.

The completeness of something

whole.

The frequency of white.

The whiteness of white.

The open space.

The nothing of open space.

The accumulation of nothing.

The nothing plus nothing that is still nothing. The

nothing plus nothing that is still transparent.

The horizon.

The horizon that always exaggerates the proximity of the horizon.

The possibility of infinity.

The visibility of infinity.

The visibility of the weather.

The visibility of other worlds.

The sense of seeing beyond sight.

The plain circumstance.

The now.

The perpetual now.

The unsuspendable now.

The no-other-than-now.

The treelessness.

The treelessness that provokes no desire for trees.

The views.

The views in the scale of the planet.

The openness.

The continuity.

The fool-me-endlessness.

The being faraway.

The feeling of being surrounded by faraway.

The sense of place.

The palpable sense of place.

The with-my-eyes-closed-sense of place.

The possibility of being present.

The sense of being present.

The being present.

The unsolicited awareness.

The ineluctable awareness.

The sheer awareness.

The solitude.

The solitude of distance.

The solitude of only.

The solitude of no way back.

The cool air.

The cold air.

The nothing but air air.

The air that is spirit not thing.

The wild, wild air.

The largeness of the moon.

The closeness of celestial bodies.

The light from non-terrestrial sources.

The shadows.

The darkness of shade.

The darkness of light withdrawn.

The black earth.

The black sand and the black ash and the black rocks.

The pink pumice.

The unnatural looking natural red earth.

The rocks.

The rocks shaped to platonic stardom.

The rocks in their organic ambiguity.

The basalt everywhere.

The basalt with its liquid past.

The basalt: cool and cracked, and whole even when in pieces.

The erratics.

The always solitary erratics.

The desert.

The unbroken emptiness of the desert.

The not nothing of the desert.

The absence of threat.

The absence of threat.

The mystery.

The mystery that is chaperone.

The mystery that accompanies the light: dark and bright.

The wind.

The delicacy and violence of the wind.

The indifference of the wind.

The stillness when it is still.

The silence when it is still.

The weather that is wildlife.

The weather.

The weather—sublime and dangerous, wild and unknowable.

The simplicity.

The clarity.

The youth.

The chance.

The opportunity.

The desire.

The absence of the hidden.

The absence of secrets?

The feeling of the absence of secrets.

The unused.

The unoccupied.

The uninhabited.

The absence of hierarchy.

The transparence of time and space.

The transparence of place.

The crazy infant geology.

The unworn and the broken and the always complete geology.

The self-evident geology.

The water.

The water.

The water.

*

Q.—What is a soul possessed by isolated insentient forces?

A.—An island zombie?

__________________________________

Excerpted from Island Zombie: Iceland Writings by Roni Horn. Copyright © 2020 by Roni Horn. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Roni Horn

Roni Horn is an artist and writer whose books include Another Water, Wonderwater (Alice Offshore), Weather Reports You, and Roni Horn aka Roni Horn.