Now You Can Eat Like Your Favorite Writer!

Recipes by Jeffery Renard Allen and Aimee Bender, from The Artists' and Writers' Cookbook

The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook is a collection of personal, food-related stories with recipes from 76 contemporary artists and writers. Inspired by a book from 1961, The (original) Artists’ & Writers’ Cookbook included recipes from the likes of Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Marianne Moore, and Harper Lee. This new version includes stories and recipes from Anthony Doerr, Leanne Shapton, Joyce Carol Oates, John Currin and Rachel Feinstein, Ed Ruscha, Neil Gaiman, Edwidge Danticat, Aimee Bender, Gregory Crewdson, James Franco, Francesca Lia Block, Swoon, Nelson DeMille, Rick Moody and Laurel Nakadate, Nikki Giovanni, T.C. Boyle, Lev Grossman, Roz Chast, Heidi Julavits, Marina Abramović, Curtis Sittenfeld, Julia Alvarez, and many others.

I first ate nyama choma in Nairobi in the summer of 2006, during my very first trip to the African continent. A friend took me took a popular restaurant called Carnivore—the name says it all—and it was truly the best thing I had ever tasted (suckling pig and bunny chow are close seconds). Since then, I have enjoyed the dish more times than I can count in Tanzania, my wife’s homeland. In Kiswahili, the phrase nyama choma literally means “roasted meat,” but everyone knows that the meat in question is goat. The meat-loving Masai have been eating nyama choma for centuries, long before someone came up with a name for it in Kiswahili.

(East African joke:

Waiter: What would you like to eat?

Masai man: Meat.

Waiter: And would you like something to drink with that?

Masai man: Yes. Meat.)

In Tanzania, a trip to a nyama choma restaurant is like going to a five-star restaurant in America or Europe; it’s a treat, as well as a sign of privilege and prestige. For that reason, Tanzanians usually reserve the dish for special outings with family, friends, or colleagues, or for wedding receptions.

If you don’t live in Tanzania or Kenya, your first challenge will be finding good goat meat. In Nairobi or Dar es Salaam, the goat is always served fresh, meaning that it was killed the very same day that you eat it. So fresh goat is the rub. Otherwise it’s an easy dish to prepare.

Nyama Choma (Roasted Goat)

– 2 pounds goat ribs salt to taste

– sliced onions and tomatoes

One kilo (2 pounds) is enough meat for 2 people. As for what cut of the goat to choose, I have found that the ribs are the tastiest part.

Salt the meat. That’s it. No marinating, no fancy spices or sauces—none of that. The charm of nyama choma is the fresh meat taste. Put the meat on the grill to roast over a charcoal fire. Keep the flame low so that the ribs cook slowly. It will take a full hour for the meat to roast.

In Kenya, people typically kill the hour by drinking beer and talking. In Tanzania they usually eat small plates of fried food such as chipsi mayai, two eggs fried over easy with strips of white potatoes (french fries). Or they simply eat a plate of chips with salt and ketchup (called “tomato sauce” in Tanzania) or a plate of fried yellow plantains.

Once the hour is up and the meat is done cooking, chop the ribs into small chunks (tips). If you don’t have a machete, use a sharp knife. The meat is always served with a simple salad of sliced onions and tomatoes. You may also add a side dish of mchicha, spinach boiled with a bit of tomato, onion, salt, and olive oil. You can even prepare some ugali, dough made from maize flour, a staple that most Tanzanians eat at least once a day, usually in the afternoon since it is filling. A true ugali eater knows how to shape a portion of the dough into a small ball before wrapping it around a piece of goat or spinach.

If you are a big eater, nyama choma also goes well with coucou (roasted chicken) or a whole fish like changu (snapper), so feel free to add a plate of either or both. The roasted meat is tasty but tough, so you will need to wash it down with a pint of beer or a bottle or two of soda, such as my favorite, Stoney Tanagawizi, a mild ginger beer from South Africa.

Meal done, lean back in your chair for a while feeling fat and satisfied, with a toothpick between your teeth.

A warning: if you eat your meal in the Tanzanian manner, you will have to ward off bothersome flies. Nyama choma places in Tanzania are not swanky establishments like the Carnivore in Nairobi where measures are taken to keep flies away from the food. (In Nairobi, the plastic table clothes are wiped down with kerosene.) People simply sit outside in cheap plastic chairs around cheap plastic tables and casually wave and brush the flies away. If you are clever, you will figure out exactly where to place your already-gnawed goat bones on the table so that the flies will leave you alone, allowing everyone to feast.

Jeffery Renard Allen is the author of five books, most recently the novel Song of the Shank, which is loosely based on the life of Blind Tom, a 19th-century African-American piano virtuoso and composer who was the first African-American to perform at The White House. The novel won the Firecracker Award and was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award and the IMPAC award. Allen’s many other accolades include a Whiting Writers’ Award, a grant in Innovative Literature from Creative Capital, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Bellagio Fellowship. He is a Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Virginia.

* * * *

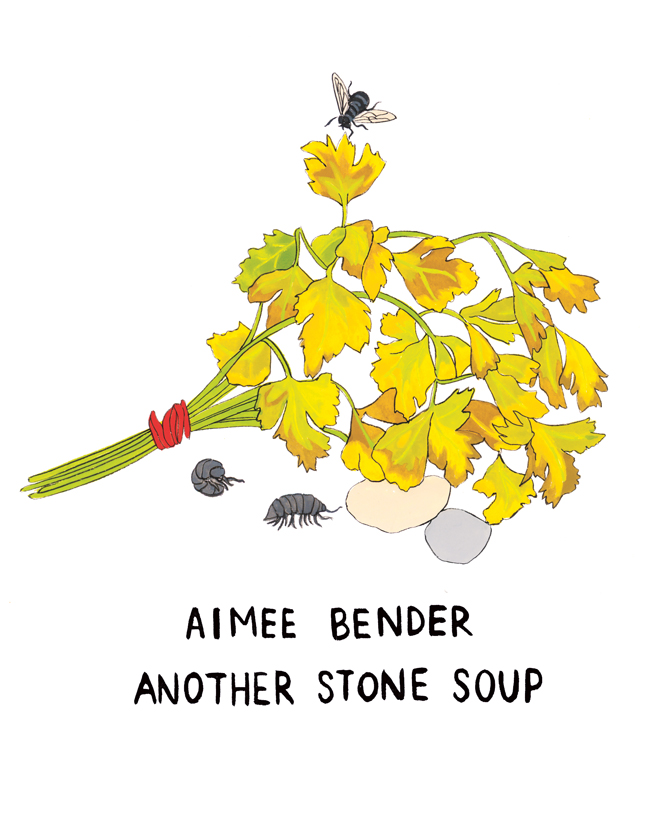

Because we had no food that day, or only the limp carrots and celery, the sprouted onion, the browning bunch of parsley, I had the children gather stones in the yard. “We will make stone soup,” I said, “just like the book.” But in the book the villagers have deliciousness to spare, they just do not want to share it. When the children returned with one smooth stone apiece I send them back to find more. I filled the biggest pot with the water I had saved from washing the vegetables on Tuesday, water that was cold from the refrigerator and a pale glowing green. To the children it looked like liquid jade, even though none of us has ever seen jade. They read about it in another book. “It is a beautiful gemstone,” said one of the children, nodding. She made sure I caught her eye and agreed. I sent them back for more stones. More.

They finally stood on a stool, one at a time, and dropped each stone into the water as it began to boil, making a tiny splash. I added the chopped carrot and celery with leaves and the onion in its greening circles and all the brown parsley including, I think, the rubber band. “What would be so good with this soup,” I said, stirring, “would be a little bit of meat! But it will be fit for a king without it,” and the children laughed with delight at the sound of the words from the story and ran outside and returned with handfuls of roly-poly bugs as we had started eating those last week and they are still plentiful plus a few dried up worms from the sandbox. I tossed them into the soup. “Flies?” I said. “What this soup would love is flies!” and off they went again. It is difficult to catch flies but we were getting wilier and we have lots of sticks and nets. It smelled good, it did, and I am sure that the stones added some dirt mineral that we needed because later I told them it was the best stone soup I’d ever had and I meant it.

After a few flies, and some stepped-on bees, and the petals of flowers we had identified as ok, and even the thin snappings of bark from a tree, I did one last stir and let it simmer for forty-five minutes during which the children and I played a few games of “Go Fish,” the idea of fish being entirely abstraction by this point. They had gotten so skilled at distracting their hunger but even so at the end H. was throwing himself at the wall as if it were a game and I. and L. were rolling over each other and sticking teeth on the other’s arm as if it was a violent kiss but we all knew better.

“Soup!” I said, and they ran in a line and I gave each a cup, a fine cup, our best china, with floral etchings on the side, there was no shortage of those, and I drained the soup and we had about seven cups of a clear broth, and it smelled heavenly. Each child had a cupful and then me too, and then enough for a round two, and I did not have bread but we were lucky enough to find the old broken bits of crackers in a box in the far back of the pantry that some liked to sprinkle in the soup itself. I taught them to say “Bon appétit,” which they found very funny. “Once,” I said, “people would leave their homes to go into little buildings and read a big card listing lots of foods on it and tell a person what food they would like and that person would then bring it to them, cooked, on a plate!” They loved those stories the best, sipping from their cups with wide eyes and then laughing with amazement. It all seemed so quaint to them.

For dessert, a bit of drawing to make a pie of blue crayon that I carefully cut into many equal slices. “What is blue flavor?” asked J., accepting his, and I said, “sky,” to give them a little hope since we still have that, and J. touched his tongue to the paper with care.

Aimee Bender is the author of five books, including The Girl in the Flammable Skirt and the bestseller The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake. Her short fiction has been published in Granta, Harper’s, The Paris Review, Tin House, and more, as well as heard on “This American Life” and “Selected Shorts.” She lives in Los Angeles and teaches creative writing at USC.

* * * *

Excerpted from The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook: A Collection of Stories with Recipes © 2016, edited by Natalie Eve Garrett, published by powerHouse Books. Illustrations and hand lettering © 2016 Amy Jean Porter.