Not-so-happy 100th birthday to Ireland’s Committee of Evil Literature.

One hundred Februarys back, the Irish justice minister Kevin O’Higgins took it upon himself to “stem the tide of filth” coming into his newly free state.

O’Higgins assembled the Committee of Evil Literature, which is unfortunately just what it sounds like, to function as an early state censor for newspapers, books, plays and films that conservative leaders considered dangerous—or just plain unwholesome—to the Irish public.

As the Irish Independent reported earlier this month, the official task of the Committee was to consider “whether it is necessary or advisable in the interests of public morality to extend the existing powers of the state to prohibit or restrict the sale and circulation of printed matter.”

Driven by the Catholic Truth Society and “consisting of three laymen and two clergymen (one Roman Catholic and one Church of Ireland),” this gang of rivals met at 24 Kildare Street, Dublin, from February to December 1926.

Per their brief, the group considered dozens of allegedly indecent texts, all with an eye to settling the question: should the state act as censor? After half a year of yum-yucking, they decided: yes.

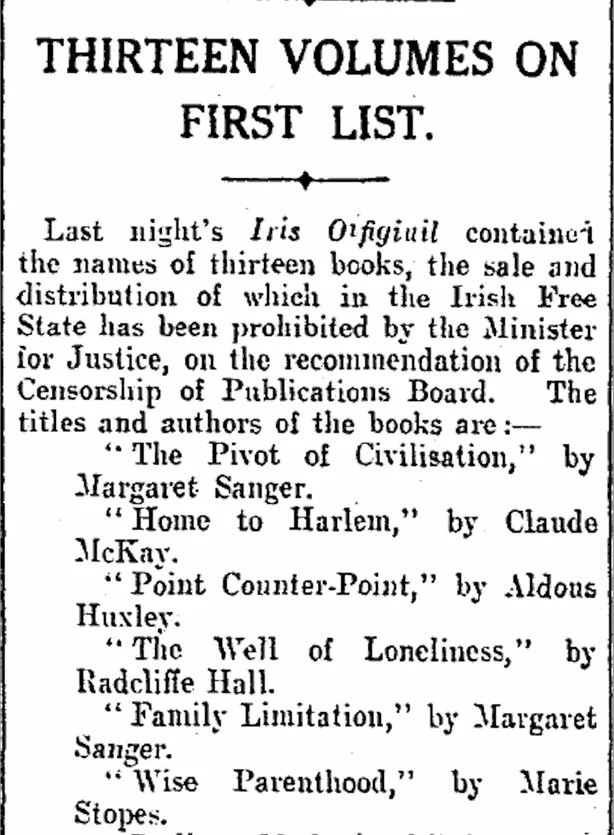

The first books banned under the CPA, published in the Irish Times.

The first books banned under the CPA, published in the Irish Times.

Off the committee’s report, the government passed the Censorship of Publications Act in 1929. The Censorship of Publications Board was officially formed the year after. Armed with the law, this powerful body was active in banning literature in Ireland until 2016.

The crossfire was scattershot but unsparing. Pulp fiction was a no-go under the censors, as was news deemed too violent. In some cases, books that failed to lionize fallen Irish heroes were put on the chopping block. Novels dealing with adolescence, contraception, sex, or abortion, like Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls, were banned. But so was Oscar Wilde.

Many international writers were withheld from the public during the censors’ reign. Books by Joseph Heller, Richard Yates, Rona Jaffe, Claude McKay, and Jack Kerouac were prohibited.

In addition to misshaping public discourse, the censors affected many local writers’ ability to make a living. When novelist John McGahern’s book The Dark was banned in 1965, he was dismissed from his teaching post and had to find work in England.

Because the board didn’t answer to the public, non-logic and personal taste prevailed. According to Aoife Ryan-Christensen at Brainstorm, “Frank O’Connor’s English translation of the Irish poem The Midnight Court was banned in 1946 because it was a ‘bad translation,’ according to one censor.” But the man in question later admitted that he did not even speak Irish.

As the censors grew more powerful, so did resistance efforts. The board’s powers were cramped some in 1946, when an appeals process was added to the law. And again in 1967, when term limits were put on book bans. But it took several more decades to pry the CPB leash off the culture.

It didn’t help that the Irish office was notoriously clandestine about its procedure and methods. According to Dr Aoife Bhreatnach, the historian and host of Censored, a podcast exploring Ireland’s blacklist, “there are very few records from this office of its daily workings.” Committee transcripts were officially made public in 1995.

In a moment where book banning and state censorship is on the rise this side of the pond, we do well to look back at the Committee that gave itself the power to distinguish good from evil literature.

It’s not the best birthday to celebrate this February. But as a recent cautionary tale, it’s a wise one to remember.

Image via

Brittany Allen

Brittany K. Allen is a writer and actor living in Brooklyn.