Not Just a Fashion Statement: How Purses Are Used as Political Tools

Kathleen B. Casey Explores the Connection Between Black Women’s Purses and the Civil Rights Movement

When Rosa Parks boarded a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1943, James Blake was behind the wheel. After Parks paid her fare, Blake ordered her to get off the bus and then board again at the back, as was the custom. When Parks refused, Blake attempted to drag her off the bus. Thinking quickly, Parks recalled, “I dropped my purse. Rather than stoop or bend over to get it, I sat right down in the front seat and from a sitting position I picked up my purse.” Parks knew that strategically “dropping” her purse could give her an opening to reach into and enter a space in which she was otherwise not welcome. Once sitting, she warned Blake, “You better not hit me” and he didn’t.

More than a decade before she became one of the most recognizable faces of the Civil Rights Movement, Rosa Parks understood that purses could function as powerful political tools. Understanding this purse-centered prelude to Parks’s 1955 arrest highlights the fact that she was not simply an “old” woman too tired to stand up. At 42 years old, she had already been pushing back against segregation for years and, on at least this one important occasion, used her purse as a tool to negotiate space, wedging her way into the white section of the bus.

In carrying their purses in the 1950s and 1960s, civil rights activists like Parks appeared to simply follow prevailing trends about how “respectable” Black women should dress. Yet, they consciously used purses to prepare to face harassment and assault while they rode public transportation, attended political events, sat-in at restaurants, and tried to register to vote.

In fact, Black and white civil rights activists both deployed purses as political tools. Oral histories, memoirs, diaries, monuments, and photographs reveal how they used purses in clever and creative ways to challenge existing power structures. Purses helped Black women protect themselves in a racist, sexist climate that fundamentally denied them their value and dignity. And although they have largely been left out of the history of Black armed self-defense, they also used purses to shield their bodies and discreetly arm themselves.

White women often faced different kinds of risks than Black women, but they, too, used purses to achieve political ends. However, white women were more often able to use the advantages of their skin color to maintain direct control of and access to their purses. Most importantly, white female activists strategically prepared the contents of their purses to help them endure lengthy sit-ins and prison sentences.

But the women themselves lovingly called the bags in which they carried their uniforms “freedom bags.”

By the 1950s, purses, bags, sacks, and suitcases had been closely associated with women’s work and travel for many decades. Black women in the early twentieth century attached special meaning to the bags they packed when they boarded segregated trains to migrate North. Oral histories reveal that some Black women who migrated to Washington, DC, in the 1920s referred to the bags they took on northbound trains as “freedom bags.” During the Great Depression, Black domestic workers gathered on the street corners in the Bronx (dubbed the “Bronx Slave Markets”) clutching their bags. As they waited for white women to select them for a day’s work, they huddled on benches or leaned against walls holding their purses and paper bags containing their uniforms.

Black reformers like Ella Baker and Marvel Cooke referred to the “invariable paper bundles” the workers carried as “disreputable”; they appear to have been concerned that these working women were on display and could be picked up by men for nefarious purposes. But the women themselves lovingly called the bags in which they carried their uniforms “freedom bags.” Because they no longer “lived in” the homes of white families as domestic servants, the bags allowed them to walk or ride to work with pride, adorned in their own clothing instead of a uniform that indicated the subservient nature of their employment.

Since the end of enslavement, keeping up appearances had been of particular political import for Black women. Indeed, Black women have historically been viewed by whites as unclean and licentious and therefore undeserving of protection. But at the end of the nineteenth century, Black women developed a “politics of respectability” that had a strong visual component. Many self-consciously dressed and groomed themselves in order to undermine white claims that they were uncivilized, promiscuous, and unkempt.

Dressing up was also a strategy that many Black women used to enhance their own sense of dignity.

However, Black conceptions of respectability were neither unchanging nor monolithic; indeed, they varied across class and region and did not go unchallenged. In different contexts and historical moments, many working-class Black women carved out their own notions of what it meant to be “respectable.”

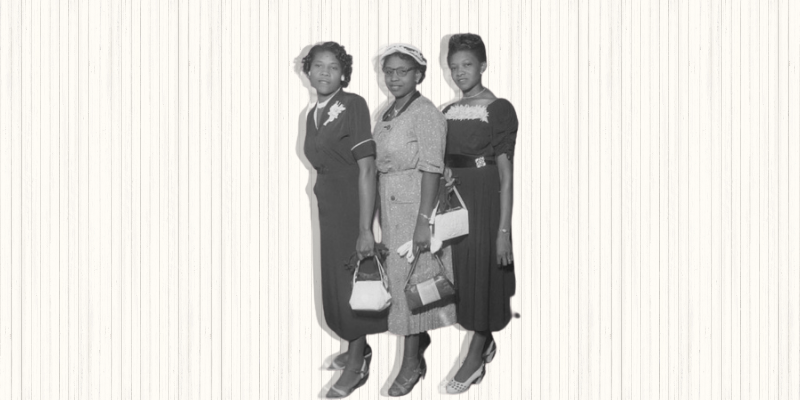

Yet, in the context of the Civil Rights Movement in which photographers created countless visual records of protests, many Black activists in the 1950s and 1960s continued to emphasize the importance of looking respectable. Impeccably clean and demure dress was particularly important where Black women were regularly subject to white surveillance. Dressing up was also a strategy that many Black women used to enhance their own sense of dignity. Black fashion designer Reginald Thomas described growing up in Chicago as the son of a maid in the early 1960s. Thomas’s mother “always pride [sic] herself she always made sure that her hair was in place. Back in those days women had gloves, purse, hat. That was the most important thing for them.”

Thomas noted that he “grew up in a[n] era where women were polished as far as you wouldn’t walk out the house without your hair being combed. You always had to have a purse, gloves, hat. Everyone had to be groomed….Even if [the men] were unemployed, they would have…groom[ed] themselves a certain way.” In the 1950s and 1960s, Thomas said, “[T]here were dos and don’ts and rules and regulations of appearance.”

Because dress had long been thought to reveal one’s inner character, these accessories were an important arena for Black women attempting to overcome deeply entrenched racist stereotypes that they were hypersexual. In addition to hats, hosiery, and purses, in the 1950s a woman’s gloves helped avoid inadvertent intimacy with men. Indeed, short white gloves were particularly popular when gender roles contracted during this decade.

They also indicated that the women who wore them did not do dirty work. It is not surprising, then, that a virtuous woman was expected to wear a girdle and gloves. When they were not being worn, white gloves could be kept clean inside a compartment of a tidy, organized purse. It is no coincidence that, in the mid-twentieth century, the term “pocketbook” was being used as a euphemism for women’s genitalia. Though gloves communicated a particular message by themselves, the combination of a clean, matching pair of gloves, hat, and purse suggested an organized, polished, pure woman.

At the height of the school desegregation crisis, young Black girls and women also used purses to protect themselves as they gained new access to formerly all-white spaces.

Historically, Black women have disproportionately faced related charges of being physically and biologically unclean. Historian Tera Hunter has persuasively argued that, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many white families believed Black domestic workers were “pathological agents of contamination” who might sicken the whole family by passing on deadly diseases like tuberculosis. This hyper-focus on the sexual and hygienic cleanliness of Black girls’ and women’s bodies provided a rationale for some whites to continuously violate their bodies in search of signs of uncleanliness.

For example, in the 1930s, a young Mabel Williams, whose mother was a maid for one of the wealthiest families in North Carolina, had her skirts lifted by white women who did not trust her to wear clean underwear. In such a context, Black women who coordinated their gloves, hat, and purse and kept them all clean guarded themselves against such accusations. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activist Roberta “Bobbi” Yancy described this as “the church lady look.”

Yet, Black women carrying purses did more than just follow the rules and regulations of appearance. Since the police and judicial system refused to protect Black women’s and children’s bodies, Black women used their purses to protect themselves. In the late 1950s, Daisy Bates, who was a local leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), faced considerable danger when she escorted the Little Rock Nine to Central High School during Arkansas’s desegregation crisis. Bates was always impeccably dressed and ready to meet the media; she often wore matching earrings and a necklace, donned short black gloves, and carried a structured black leather purse shaped like a trapezoid, which was particularly popular at the time.

But Bates knew firsthand how white men could violate Black women’s bodies without facing legal consequences. When she was 8 years old, Bates discovered that, while she was still a baby, her biological mother had been raped and murdered by three white men. Bates vowed that “someday I would get the men who killed my mother.”

Bates channeled her anger over this trauma into her efforts to protect the Little Rock Nine. She knew that students and their families who attempted to integrate all-white schools could face a wide range of potentially devastating consequences—from job loss and eviction to school closures, harassment, physical assault, and even death. For these reasons, the Little Rock Nine met at Bates’s house every morning, and she personally escorted them to school throughout the crisis. But Bates, who was the only woman permitted to speak during the main program of the March on Washington in 1963, did not exclusively rely on her husband and male friends to keep herself safe. She carried her own .32-caliber pistol, which she kept in her purse.

At the height of the school desegregation crisis, young Black girls and women also used purses to protect themselves as they gained new access to formerly all-white spaces. Bobbie Steele remembered that in the mid-1960s her mother, Mary Laney Hodges, was one of the first Black students to integrate Mississippi’s Delta State Teachers College. Steele recalled that upon starting school, her mother purchased a gun: “I think it was a .32 . . . to protect herself.”

Fearful of being assaulted, Hodges took her gun with her and “as she would ride to school she’d put it on the seat of her car. And when she got out, of course she’d take it out and take it in the school with her and put her purse up.” Hodges knew that in the mid-1960s, where schools remained racial battlegrounds, a young Black woman could not openly carry a gun. But a purse offered her privacy in public, and hiding a gun inside her purse provided her with powerful protection even though she appeared to be alone, unarmed, and otherwise unassuming.

__________________________________

This article includes excerpts from The Things She Carried: A Cultural History of the Purse in America by Kathleen B. Casey and published by Oxford University Press in the US © Kathleen B. Casey, August 2025. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Footnotes have been removed to ease reading.

Kathleen B. Casey

Kathleen B. Casey is Director of the Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program and Professor of History at Furman University in South Carolina. She is the author of The Prettiest Girl on Stage is a Man: Race and Gender Benders in American Vaudeville.