Not Everybody Loves Sebald: 5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

John Banville on Picasso, Lauren Oyler on Sebald, Adam Hochschild on The 1619 Project, and more

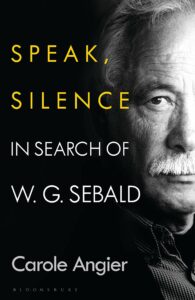

The very best reviews this week include John Banville on John Richardson’s A Life of Picasso, Adam Hochschild on Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project, Lauren Oyler on Carole Angier’s Speak, Silence: In Search of W. G. Sebald, Marie-Helene Bertino on Claire Oshetsky’s Chouette, and Lauren Le Blanc on Cathy Curtis’ A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s “Rotten Tomatoes for books.”

*

“A Life of Picasso, which will never now be finished—it stops at 1943, short of the last 30 years of Picasso’s life—is as much a portrait of an age, in all its color and its tragic, and often trivial, goings-on, as it is a biography of one of the titans of that age … One of the ghostly figures that haunted Picasso all his life was that of his adored sister Conchita, who died in 1895, at the age of seven. Pablo, a prodigy at 13, had made a vow to God that if Conchita’s life was spared he would never paint again. Richardson repeatedly refers to this as the ‘broken vow,’ though it is hard to see how it was broken, since God took no notice of the boy’s promise. All the same, ‘the beloved child’s early death would cast an inescapable shadow over virtually all of Picasso’s relationships with women, especially that with Marie-Thérèse.’ Certainly, as the years went on, the image of his lover became melded with that of his lost sister … It is not vision, or sexuality, or perhaps not even art, that is the constituent of Picasso’s greatness, but his unrelenting program to deny human beings the comfort, and the escape, of truth—manmade truth, that is. Picasso would counter Keats’s dictum that ‘beauty is truth, truth beauty’ by staring the poet hard in the eye and saying, Yes, and both are lies. As T.J. Clark puts it: ‘Is not [Picasso’s] the most unmoral picture of existence ever pursued through a life? I think so. Perhaps that is why our culture fights so hard to trivialize—to make biographical—what he shows us.’ Yes, biographies stylize, and in the process to some extent trivialize, a life, yet Richardson’s enormous labor of love does throw light upon a dark, often destructive, but always creative modern master.”

–John Banville on John Richardson’s A Life of Picasso: The Minotaur Years (The New Republic)

“Has a book ever come into the world when at least four other books were already in print attacking it? … It is not without flaws, which I will come back to, but on the whole it is a wide-ranging, landmark summary of the Black experience in America: searing, rich in unfamiliar detail, exploring every aspect of slavery and its continuing legacy, in which being white or Black affects everything from how you fare in courts and hospitals and schools to the odds that your neighborhood will be bulldozed for a freeway … Several times, a 1619 Project writer makes a bold assertion that departs so far from conventional wisdom that it sounds exaggerated. And then comes a zinger that proves the author’s point … A broader issue in the book is that, with a few exceptions, such as Muhammad’s excellent article about the brutal world of sugar cultivation, the reader can too easily leave with the impression that the heritage of slavery is uniquely American. It’s not … To be clear: Eliminating these minor shortcomings would not have prevented the torrent of outrage against this whole venture from Trump and his followers. From people determined to inflame a sense of grievance by proclaiming that any hint of Black advance means white victimization, such venom was inevitable. It may be too much to expect in this deeply divided country of ours, but my hope is that the multifaceted and often brilliant ways in which this book’s authors etch the Black experience will inspire not resentment but empathy. And perhaps emulation.”

–Adam Hochschild on Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story (The New York Times Book Review)

“This is not a takedown, but I’m also not here to reheat the bland appreciation for Sebald shared by what feels at times like everyone I know. Since The Emigrants was celebrated by Susan Sontag as ‘an astonishing masterpiece’ in 1996, he’s been praised by Cynthia Ozick, J. M. Coetzee, Nicole Krauss, Robert Macfarlane, and James Wood, among many others; in the English-speaking world, he’s become about as popular as an experimental author of what his friend, occasional translator, and The Rings of Saturn muse Michael Hamburger called ‘essayistic semi-fiction’ can be … Carole Angier’s Speak, Silence is the first major biography of Sebald to appear in any language, and her approach both confirms his swift canonization in the Anglophone world and suggests there is something a little weird about it. What accounts for his dizzying ascent? … Wouldn’t it be nice, I thought as I accepted this assignment, to feel a passion that drove me to publish such ludicrous statements? But if I couldn’t be converted, I wondered whether Sebald’s might prove the level of excellence at which I could experience that rare thing, a respectful difference of opinion … Almost surreal, his prose resembles a hotel described in The Emigrants: ‘The rooms are furnished in a most peculiar manner. One cannot say what period or part of the world one is in’ … From the beginning, it is difficult to trust much of what Angier says, and her kitschy style made me long for Sebald’s Gothic melodrama, and want to defend him from her misguided approach.”

–Lauren Oyler on Carole Angier’s Speak, Silence: In Search of W. G. Sebald (Harper’s)

“… searing and ethereal … The fable’s metaphors leap organically from the page, contouring the dichotomy as capably as do Neel’s oils: a newborn’s vulnerability and destructive power; the mother’s isolation; her tender, feral nature … While ambiguity in fables allows for interpretation, a vague idea of disability in a metaphorical construction runs the risk of reducing severe disability to animalistic comparison. Chouetteseems to answer this by focusing squarely on Tiny’s fierce love as she battles her husband and nature to allow Chouette to be wild and exact, stakes that feel frightening and true to life … In fiction, supernatural premises are notoriously hard to land, but Chouette’s final moments are among its loveliest. Human and owl meet in equal measure on the page in a crescendo of stunning lines. Just as Tiny longs for the world to meet her daughter where she is instead of forcing her into societal norms, Chouette is best met where it resides: as a harrowing and magnificent fable.”

–Marie-Helene Bertino on Claire Oshetsky’s Chouette (The New York Times Book Review)

“A biography whose disappointments often justify its subject’s skepticism of such efforts … Today, readers want a rigorous biographer whose job isn’t to flatter—or flatten—the subject … Alas, A Splendid Intelligence is no corrective in this sense. Curtis hews closely to a traditional format, keeping the biographer at a remove, occupying the role of an archivist who presents evidence on a timeline … Curtis quietly and predictably asserts Hardwick’s place in 20th century American letters as someone far more than a spurned wife … This choice strikes an oddly defensive chord. Drawing immediate attention to her relationship with Lowell merely reinforces this association … I could think of countless moments that would speak more powerfully by example. Instead, Curtis moves from that brief introduction to a largely dry and linear chronicle of her life … The book builds momentum in tandem with Hardwick’s career as her marriage with Lowell takes on a certain magnetic inevitability … Curtis’ respectable impulse to downplay the period prevents her from examining what brought Hardwick to this point in her marriage after Lowell’s infidelities and mental health interventions—and, more importantly, what she was able to accomplish after she broke loose … Where the biography picks up considerably is its final chapter … A Splendid Intelligence is an admirable work that fills a glaring void in the 20th century American literary landscape. Yet there’s something in her project that cries out for a less conventional approach.”

–Lauren Le Blanc on Cathy Curtis’ A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick (The Los Angeles Times)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.