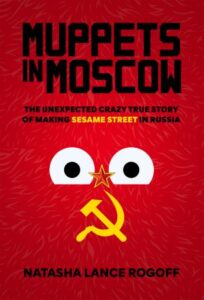

“No One Can Say No to Elmo.” The Beginning of a Journey to Bring Sesame Street to Russia

Natasha Lance Rogoff on an Unexpected Request from the Sesame Workshop

A Russian baggage handler, dressed in dark overalls, carelessly throws suitcases on the rotating conveyor belt and I watch as if in a trance, thinking back to how this journey started. Six months earlier, I was in New York presenting my documentary film on Russia at a screening hosted by my alma mater, Columbia University.

Three hundred people filled the auditorium, including two honored speakers: Carl Levin, Michigan’s longest-serving and revered U.S. senator, and Pamela Harriman, the legendary grande dame of the Democratic Party who was doing everything in her power to put Bill Clinton in the White House. In a clipped British accent, Harriman introduced my film, extolling the Russian people:

Many people think that the Russians are a passive people, just waiting with their hands out to receive aid and help from us, but that is not true. This film shows the determination of Russians to create a new, more open society.

After a panel discussion, I was approached by Gary Knell and Steve Miller, Sesame Workshop’s senior vice president of corporate affairs, and the vice president of international television, respectively. They introduced themselves and asked if I could help them bring Sesame Street to Russia.

I froze. I couldn’t imagine why these television executives would possibly think I could help them produce a children’s comedy show, especially after just watching my film’s grim account of Soviet Russia.

Bemused, I explained that I’d never worked in children’s television and had even less experience with actual children.

Knell saw my confusion but was not easily put off. “Come on, just meet with us,” he said with a twinkle in his eye. “No one can say no to Elmo, Right?”

Although I felt I was an entirely wrong fit for a children’s show, the offer intrigued me. I agreed to meet their team the following week at Sesame Street’s headquarters (referred to by those in the know as “the workshop”).

*

“The workshop” is on West Sixty-Fourth and Broadway. When the elevator doors opened, I found myself in an alternate universe—walls painted in bold primary colors and giant framed photographs of Big Bird and Elmo staring back at me. Fresh-faced, earnest twenty-somethings sat at desks adorned with playful kiddie toys—plastic action heroes, rubber balls, and stuffed Muppets.

The sight of these noble crusaders for children’s enlightenment made me feel that I did not belong, as did the smartly dressed woman with perfectly coiffed hair who led me to a conference room. In my jeans, T-shirt, and hoodie, I hadn’t dressed appropriately for the interview. I felt like an idiot.

But it was too late to do anything about that now; there was Knell striding into the conference room accompanied by a tall, slender man.

It was nice to see Knell again, and he introduced me to the vice president of international production, his colleague who’d be my boss if I were to take the job. Seated at a conference table, Knell explained that for some time he and his Big Bird colleagues had been trying to bring Sesame Street to Russia. In fact, the company president had appeared before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee for Foreign Affairs chaired by Senator Biden in January 1992 and had testified that Sesame Street could help foster democratic values in Russia’s postcommunist society.

I nodded along, but I still didn’t get where I would fit in.

Apparently, my first role would be to find a Russian broadcast partner, someone who could coproduce an original Russian version of Sesame Street. Knell was complimentary and persuasive, explaining how my substantive Moscow TV connections were exactly what was needed.

Russia seemed to be in political limbo, teetering between its communist past and an unknown future. Such an unstable environment did not seem like fertile ground for the Muppets—or a major career move.

I asked if they intended to dub the American show or create an original production, which would be very expensive.

Knell replied, “We’re envisioning half of the Russian series would be original production filmed in Moscow and the rest would be dubbed from Sesame Street’s international library.”

I doubted the country’s new government would spend money on Muppets when they had so many other, more pressing problems. I then asked if they expected Russian State Television to pay for the production.

Knell picked up a transcript from the congressional hearing and began reading the moving testimony of Elena Lenskaya, the Russian deputy minister of education:

Our system needs new openness and integration into the global world outside. Our kids have been isolated from their peers in the world for a very long time. But in order to communicate, kids have to share something… Let them share not The Terminator and not Rambo, which is now the case [on Russian television], but Sesame Street.

I was impressed. “That’s amazing to have such an endorsement,” I said. Knell shot me a playful smile. “That’s why we need you—why Russia needs You.”

Suppressing a grin, I hedged, suggesting that plenty of people with experience in children’s television were better suited to help Sesame Street. I also emphasized that I had only ever filmed with a small documentary crew and relying on others has never been my strong suit.

But Knell continued the flattery, so much so that I almost wanted to take the job on the spot just so he’d stop embarrassing me.

But then the head of international production, who had not yet uttered a word, contorted his face into a pained expression and finally spoke. He said he’d been on a trip to Russia a year before, when his Russian hosts had put him up in a disgusting hotel with a broken window and no food. Stretching his neck from side to side and grimacing, he offered, “None of the Russians I spoke with seemed to care about Sesame Street; all they wanted was foreign currency.”

A flash of irritation crossed Knell’s face as my “future boss” continued.

“I’m not convinced it’s the right time to do a full-scale coproduction in Russia,” he said. He then argued in favor of another approach—easing instead into Russia by doing Open Sesame, an international version of Sesame Street that requires a much smaller amount of original production. Clearly there was some tension between the two men.

I changed the subject, asking what the expected budget would be.

Knell explained that the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the American government’s arm for foreign assistance, was on the verge of providing significant funding to Sesame Workshop to support Sesame Street in Russia. He disclosed that more would come later from Russian state television or private Russian investors, bringing the total production budget for Ulitsa Sezam to between six and ten million U.S. dollars (between $15 and $20 million today). And this didn’t even include in-kind contributions that Russian television would make, such as the studio and equipment.

I nearly fell off my chair. The entire budget for my PBS television special on Russia didn’t even come close to a million. Moreover, American dollars could buy ten times the talent and staffing in Moscow than it could in the West.

At the end of our meeting, Knell reassured me that I was “the perfect person to help,” and that “now is the right time.”

*

Over the next few days, I scoured the bookshelves at my local library, devouring everything I could find about Joan Ganz Cooney, the founder of Sesame Street, and Jim Henson, the legendary creator of the Muppets. I knew the Sesame Street Muppets generally, in the way that everyone knew of them. But I hadn’t watched the popular program as a child and certainly not as an adult. Now, I binge-watched every VHS cassette I could lay my hands on, learning as much as I could about the format, messaging, songs, tone, and every Muppet on the show.

the prospect of the Sesame Street Muppets modeling important liberal values like tolerance, compassion, and cooperation stirred something within me.

For the rest of the week, I debated the offer. The production of a television series with fifty-two half-hour episodes would be difficult anywhere, but in Moscow, especially so. Almost as soon as the Soviet Union disbanded, the country had plunged into chaos as factions battled for power. Russia seemed to be in political limbo, teetering between its communist past and an unknown future. Such an unstable environment did not seem like fertile ground for the Muppets—or a major career move.

I also had some concerns about the potential appeal of Sesame Street to children living in the former Soviet Union. Knowing the country as I did, I wondered if Russian children would find the Muppets’ antics as amusing as kids who’d grown up in the free world. Could Elmo’s and Cookie Monster’s wacky, lighthearted banter even be translated for Dostoevskian, angst-ridden Russians?

Yet the prospect of the Sesame Street Muppets modeling important liberal values like tolerance, compassion, and cooperation stirred something within me. For nearly a century, people in the West had dreamed of Russia joining the global community of nations, sharing democratic values and objectives. Now such an awakening seemed within grasp. There was an urgency in the air, and the idea that I could be part of this momentous transformation was both seductive and intoxicating. And if the show were to become successful, having worked for a big company like Sesame Workshop might even fast-track my television career.

Money was another objective. Making a documentary had wiped out my savings, and I could barely afford rent for my tiny West Village basement studio. I’d continued to live like a student well past college, but I was thirty-two now and needed a steady job.

With only a few hours left before I had to give Knell my decision, I called my younger sister Emily, a radiologist living in North Carolina with her two kids and her husband, a vascular surgeon. Among the five siblings, Emily is the sensible middle child who can be counted upon to provide smart but conventional advice.

When I shared news of the job offer with Emily, she laughed. “You do realize this is a show for children—about which you know nothing?” She then continued in the same vein, arguing that working in Russia was a bad idea. “These are your prime childbearing years. Have you considered, if you take this job, you might never have kids? Or maybe you’re planning to fall in love with a Russian and have little Russki babies?” she joked. I was used to my bohemian life being the butt of family humor. Truthfully, ever since my ex-fiancé had dumped me three years earlier, I hadn’t given much thought to having kids. Still, her teasing stung.

I wanted to tell her that I needed to take this job. I wanted what Knell had said about me to be true. I wanted to believe that I was “perfect” for the Moscow production, and that—for once—my sister was wrong.

“I’m going to bring the Muppets to Moscow,” I heard myself say, deciding

all at once.

The next day, I called Knell and told him “Yes.”

*

Suddenly, I feel a push as a heavyset man brushes against me and grabs his suitcase off the conveyor belt. I spot my beat-up black bag and lug it to the customs line. Getting through customs in Soviet Russia as a filmmaker was always scary.

You never knew if your video tapes—years of work—would get seized, if you’d get arrested, or worse. At least this time, I’m not bringing anything incriminating with me… unless videos of Elmo dancing the “Jive Five” is considered contraband by this new regime.

_________________________________

Excerpted from MUPPETS IN MOSCOW: The Crazy Unexpected True Story of Making Sesame Street in Russia by Natasha Lance Rogoff. Available now via Rowman & Littlefield October 17, 2022.

Natasha Lance Rogoff

Natasha Lance Rogoff is an award-winning American television producer, filmmaker, and journalist of television news and documentaries in Russia, Ukraine, and the former Soviet Union for NBC, ABC, and PBS. Lance Rogoff executive produced Ulitsa Sezam, the Russian adaptation of Sesame Street, between 1993 and 1997. She also produced Plaza Sesamo in Mexico. In addition to her television work, Lance Rogoff has reported on Soviet underground culture as a documentary director and magazine and newspaper writer for major international media outlets. Today, Lance Rogoff creates current affairs videos and is the CEO and founder of an ed-tech company that produces KickinNutrition.TV, a children’s cooking and nutrition program. She is an associate fellow at Harvard University’s Art, Film, and Visual Studies department. Lance Rogoff lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts and New York City.