I’m still working one night a week at the Mexican restaurant because my checks from the group home barely pay the rent. Tonight after my shift I sit at the bar. Dan, a regular, slouches on his stool next to me, his fat fingers toying with my pack of cigarettes before he asks to bum one. His eyes are red, their lids heavy. He rubs his unshaven cheek, and I think how he looks older than he is. I wonder if I look the same. He lights the cigarette, ignoring the city’s smoking ban, and asks me about the group home. Rodrigo comes to mind. Just before I left the 401 this week, he told me he had to go to court to testify to a judge about how he’d been molested for years by his brother John.

“You nervous?” I asked him.

“Yeah,” he said. “My mom told me to drop it. She scared.”

He needed to be reassured that he was doing the right thing, but I didn’t know what to say. I pulled him close and patted his shoulder, softly offering, “You’ll be OK.”

But I don’t tell Dan about Rodrigo. Instead I talk about a harmless public meltdown Benny had last week at Jamaica Center when we didn’t see the movie he wanted. For now, I keep Rodrigo to myself.

When I return to the 401 the following week, everything is in chaos. Montana has been fired from her job as a security guard because she was caught smoking weed. Sybella has stopped going to night school. Caridad, who’s been AWOL, showed up high last night at 4:00 a.m. And Benny seems to have developed a Napoleon complex, not allowing anyone to use the phone or the TV without his permission. By the time I get around to Rodrigo, I can tell something’s happened. He has trouble making eye contact and is high-strung. Earlier he snapped at Sybella when she tried to talk to him about organizing their joint birthday party.

We sit together in the office, and he seems preoccupied. He wants to talk only about a man he’s met at the local gay and lesbian community center.

“He just my type,” Rodrigo says, followed by a stream of giggles. “He got a goatee.”

Gena suggested that Rodrigo check out the community center. They have an after-school program that offers art and music classes and gives LGBTQ youth a safe place to socialize. The administrative staff in our program had tried other ways of engaging Rodrigo in less self-destructive activities. There was a short-lived mentoring program where residents were matched with adults in the community.

Most of the mentors were unprepared to deal with the struggles the residents had. We canceled Rodrigo’s mentorship after he decided to sunbathe in transparent briefs with his mentor when they went to the beach.

Rodrigo tells me that the man with the goatee operates a food cart. Rodrigo’s leg hammers up and down as he plays with the Wite-Out on Gena’s desk, unscrewing the top and taking a quick sniff.

“I told him he should invite me over to his crib after he finish work.” Rodrigo starts painting his thumbnail with the Wite-Out.

“You know that’s not a good idea.”

Rodrigo looks up, thinking I’m talking about decorating his nails.

“You don’t know anything about this guy,” I say.

“Don’t you think he’s too old for you?”

He goes back to finishing off his thumbnail. I try to find out what he likes about the guy, but all Rodrigo will say is that he has a goatee. So I steer the conversation away and ask if Rodrigo has been in contact with his father. He puts the Wite-Out down, and something in his face hardens.

“He back in Puerto Rico.”

“You told me he lives in Brooklyn with a second family.”

“Well, he got ghost when he heard I got put up in here.”

I ask why his father would move; Rodrigo shrugs. I can tell the conversation is making him uncomfortable, but I don’t stop prying. Something is being left out. Rodrigo wraps his arms around his belly, glowers.

“We almost done?” I lean back in my chair.

“Yeah, of course.” He gets up to leave. “You’re OK, though?”

Rodrigo nods but doesn’t look up as he walks out the door.

* * * *

The residents are huddled around the TV, watching America’s Next Top Model. I’m sitting at the edge of the room on a chair I’ve pulled from the dinner table. Everyone stares at the screen with rapt attention—everyone except Rodrigo, who’s pacing the periphery, his fingers flicking near his ears. He pauses, cocks his head. One hand covers his mouth, and he mutters something to himself. Montana and Sybella seem to have blocked him out, but Benny, I can tell, is annoyed. As Rodrigo begins to lap the room again, Benny blurts out, “What the fuck is your problem?”

“Watch the show,” Montana says to Rodrigo.

“Watch the show,” Rodrigo mimics, then begins to laugh. It’s a hollow, artificial laugh that goes on for too long.

The residents begin talking about Rodrigo as if he’s not there until Benny’s eyes narrow.

“How they going to put these crazy motherfuckers in here with us? You know one night he going to crack and pull some Friday the 13th type shit,” he says.

Benny leans toward Rodrigo. “Hey, don’t go chopping nobody into little pieces when they sleeping, yo.”

The other residents laugh and so does Rodrigo.

Then his face turns stony. Then he laughs again, starting to howl, clutching his gut, red-faced, bending over. I’ve decided not to jump in just yet. I’m hoping the residents can work out this dispute on their own.

“Fucking freak,” Benny says, turning back to the show. “People be treating you better if you stop being so backwards.”

This prompts Rodrigo to run up to the TV with exaggerated, faux curiosity. He looks back at the other residents and pretends to bite his nails.

“Oh, my God, who they going to vote off tonight? The anticipation is killing me!”

“Shut the fuck up, bitch,” Benny says, sitting up, his shoulders tight. The room feels tense.

Rodrigo rushes over to him, stopping just short of colliding with his legs. “You mad funny!” Rodrigo screams, only inches from Benny’s face.

I get up.

Benny turns to me, his fists clenched. “This punk better get outta my face, or I’ma make him get outta my face,” he says to me.

I wedge between them, bring Rodrigo into the office, and shut the door. He plops down and smiles so big his eyes are hidden behind mounds of cheek. I ask him if he thinks this is funny and warn him that one day he’s going to push someone too far and get punched.

“Good.”

I stare at him until we’re both uncomfortable.

“What’s going on? This isn’t like you.”

He shrugs and says he was just playing. He picks at the scabs around his wrist left by a too-tight leather wristband. If he’s feeling anxious, I tell him, he needs to talk to a staff member or his therapist. Rodrigo mouths, “OK,” his fingers now interlaced in his lap.

I get up, ask him to apologize to his housemates, then pat him on the shoulder, indicating he’s free to go. Rodrigo nods and gives me a smile that says, “I’m sorry,” then goes back to the living room. I open the logbook and start writing up the incident. Rodrigo will probably get a “level drop” because of this, ending five weeks of continued success. Often a change in status can send a resident into a streak of bad behavior. I write that I think we need to keep Rodrigo focused on his positive accomplishments. I want him to know he has a confidant in the house. I want to tell him I know what it’s like to feel alienated, different.

A noise comes from down the hall. Then a scream.

“Fucking freak!” Benny yells. I run into the living room to find Benny on top of Rodrigo, one hand around his throat, the other reared back in a fist. Rodrigo’s lips are moving, saying something over and over that I can’t make out. Not until I get close enough to separate them can I tell that he’s pleading with Benny.

“Please,” he begs. “Hit me.”

* * * *

A few days later, I’m putting out extra folding chairs in the office, setting out soda and bottled water and individual bags of chips. Rodrigo’s caseworker, Steve, is meeting with Jessica, Gena, and Laura, to discuss the incident with Benny. Steve informs the group that Rodrigo’s behavior was a result of what had happened at his hearing with the judge earlier in the week. He didn’t realize the repercussions of his allegations against his brother. John is now nineteen years old, so a criminal case will be mounted. If convicted, his brother will go to prison. Rodrigo returned to the group home frightened and confused. Steve, overburdened with eleven other cases, forgot to inform the staff at the 401 of the outcome. As a result of the incident, Steve says, Rodrigo had to undergo a psychiatric evaluation and was prescribed Risperdal.

“Risperdal?” I ask.

“An antipsychotic.”

My colleagues scribble in their notebooks. No one seems troubled by this news. Maybe they’re desensitized to this type of outcome. My throat tightens. I’m irritated with this overlit room and Steve’s shrill voice. The clinical words only dance around Rodrigo’s pain.

“Medicating him seems like a drastic response to the situation, don’t you think?” I ask.

The scribbling stops. I suggest that Rodrigo’s acting out was a cry for help. He felt overwhelmed by what he’d heard at court. I don’t mention that he probably also felt let down by the program’s failure to provide support. Aggravating Benny was his way to eclipse the pain he was feeling.

Jessica gives me a knowing look. “No one wants to medicate the residents unnecessarily,” she says. “This is a doctor’s diagnosis.”

I’m told to continue my talks with Rodrigo because he trusts me. Jessica reminds me that I’m not a trained clinician. The talks are to remain casual and should not attempt to simulate a therapeutic environment. I need to keep the team informed of what we discuss. The concern I’ve raised has been passed over, and the conversation moves on. It becomes clear that a diagnosis—even a possible misdiagnosis—reads as due diligence to the powers that be.

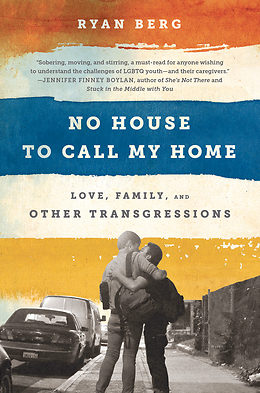

From NO HOUSE TO CALL MY HOME. Used with permission of Nation Books. Copyright © 2015 by Ryan Berg.