Ruth was the first to open her eyes.

The throb of her hand had woken her, pulsing its way through her sleep. She breathed in. Metal and sweat. An aftertaste of sea.

It had been late last night—long past her bedtime—when the woman down the end of the port had led them here. Lady Liberty. Not a statue at all, as it turned out, but a landlady, touting for business; offering a place where they could rest their poor, tired heads. They had followed her in silence, exhaustion winning out over a thousand questions, each of them just content for the moment to sleep on solid ground again. Though, actually, Ruth had found it strange dropping off without Mame and Esther below her. She had liked being in the top bunk on the ship, feeling their words as they vibrated beneath—secrets they never let her hear but that at least now she could feel.

She checked her finger. Already the base had begun to blacken.

Beside her, her father snored, eight hours of ideas clogging his nostrils. The white patch of baldness gleamed out from the crown of his head, the first bit of him to come into the world usually hidden away beneath the circle of his kippah.

Next to him in the dust her mother’s curls mingled with her big sister’s—a carpet of black, oily and slick. Like the story Tateh used to tell about the trio of women who spent their lives knitting—a widow, a spinster, and a divorcee—alone except for one another and their needles and wool. Until one day they had an argument and tried to pull apart, only to discover that they had knitted themselves together—their clothes, their hair, even their eyelashes, bound into one.

Mame had warned him to stop. She said it would give the girls nightmares.

“But Austèja,” Tateh had protested, eyes vast with confusion, “it is supposed to be a metaphor. For family.”

Ruth’s family had begun to wake now, limbs stiff from awkward folds, and then the other bodies across the floor stirred too. Ruth watched as they opened their eyes one by one, each face registering a split second between waking and realizing; remembering where they were.

America.

Arrived.

A sleep-crusty grin. And a look around for a bucket so that the men could wash their hands to begin their brand-new day; their brand-new everything.

“Have a look for one outside, girls, would you? There’s bound to be one by the port.” It was Leb Epstein who made the request, drowsy up on elbows, his gut still resting firmly on the ground.

He was a tailor who had come from the very same shtetl as Ruth and her family, accompanied by his thin little wife. She always looked at your shadow instead of at you, as if her eyes were too skinny to fit too much at once. The couple planned to travel to America first and save enough money through waistcoats and pleats to send back to the rest of their clan, just like Uncle Dovid had for them—letters of advice; certificates of introduction; pale pink flushes from sisters-in-law that couldn’t always be hidden.

Ruth put her left hand behind her back. “A bucket, Mr. Epstein? Yessir.” She repeated the word in her head as she beelined for the door, abucket abucket abucket.

She had always been eager to make herself useful; to help the adults wherever she could—barely able to walk before she had sought out the orders, the chores, the tasks that made her feel more important than she really was. Sometimes the villagers laughed at her diligence; told her she had a very old soul for her eight little years. But this morning especially she just needed an excuse—anything to get outside.

Ruth eased the shed door open, a low groan off the hinges as if they had been sleeping too. She craned her neck, preparing herself for the New York view. The skyscrapers. The cabs. The peanut vendors on every corner—every single one—Uncle Dovid wrote that he worried he was about to turn into a peanut! And Ruth thought now it sounded a bit like one of her father’s ideas, A Plague of Peanuts! The Incredible Salty Man! So she wondered if that counted as imagining; if maybe she should try to tell Tateh. Guess what guess what, America has fixed me! Or if maybe she should just stay shtum and stop trying too hard to please.

Outside the shed, America hadn’t tried at all.

The dock was deserted, quiet as an inhale.

There were no sailors.

No peanut vendors.

Nobody.

Ruth craned a little farther.

Beyond the empty quay the sea was empty too. There was no sign of their ship—not even an orange-rusted bruise smudged against the port—while, above, the sky stretched away uninterrupted, untouched, no buildings or scrapers at all. Like an uncracked glass on a wedding day, Ruth thought—an omen she hadn’t ever understood.

Until now.

Behind the shed the warehouses sat in rows, abandoned. Smashed-out windows. A barrel leaking a tongue of rust where the rainwater had spilled. The only sign of life was the maul of seagulls overhead, their wings making hard work of the breezeless air, currents that just wouldn’t run.

“Right, you runt.” Ruth’s big sister suddenly appeared next to her, eyeing the dockside wasteland. “Where would we find a pump?” Not that, really, they looked like sisters at all. Even at ten, Esther was much too like their mother—the wool-thick hair; the black eyes; the stare that cut like wire—whereas Ruth, as Esther always liked to remind her, had been born deformed, one of her eyes green and the other one brown.

Ruth never understood why the world didn’t look different colors out of each one.

But this morning, the world just looked wrong. Felt wrong. Not even a shudder from the trains running under the ground—had Uncle Dovid just been making them up? And where was Liberty this morning, Ruth wanted to know—there had been no word from her either. What if it had all just been a big fat trick?

“Esther . . .” She looked at her hand. The blackness had traveled even higher. “Esther, are you sure . . .” She wondered if the nail would fall off soon; if the seagulls would swoop down to peck it up.

And normally she wouldn’t have said a thing about her confusion. She didn’t like to complain. Most of all, didn’t like how cruel her sister could be with her weaknesses. All of them.

But this was different—this was everything.

Or at least, it was supposed to be.

“Esther, are you sure this is New York?”

Two days before they began their journey Tateh had taken the girls up to his attic, almost empty now that his papers had been carried off for the fire. He told them they could each choose one remaining item to take with them when they left—a souvenir from this life to the next.

Of course, Esther had gone first; had marched right up to the Shakespeare that sat on the top shelf of the bookcase, swathed in pale blue leather—another cow in another life. She had struggled even to carry the ton weight down, let alone for thousands of miles, but it seemed the impracticality was precisely what had made their father smile; the perfect after-his-own-heart choice.

His second daughter had opted for the compass. It was hidden half-forgotten in the clutter of the desk, a mere four words in total. North, South, East, West. But even as she held it Ruth had felt better; had run her then-unbroken finger around the rim so that her nail made a sound along the ridges, a buzz that almost drowned all the other noises out.

This morning, Esther’s voice was loudest of all. “Stupid girl!” it cried, the disdain filling the whole span of her mouth. “Don’t you remember what Uncle Dovid said?” It was a voice for the stage, her father always boasted—the finest legacy he could have hoped for. The only one, really, he would ever need. “Ellis Island,” it said now. “He told us we had to come to Ellis Island first before we were allowed in.”’ Reading from a script everyone else seemed to know—everyone except for Ruth. “All right?”

And to any audience the gesture that followed would have just looked like a kindness, a sibling affection, as Esther smiled and took her little sister’s hand in hers. “That’s why Tateh and Mr. Epstein are about to go to the immigration office.” She gave it a tug, a squeeze of reassurance. “That’s why you are shooing off with them too.” And then a twist. An extra snap. A whimper barely heard. “You didn’t think we’d traveled all that way for this, did you?”

Two hours later, having woken from her faint, Ruth sat on the tram with her father and his friend, stiffening her face into a smile, nice and wide like her sister had shown her. And maybe someday, years from now, they would come to look alike, maybe even be loved alike. An American family healed better again, the scars you could barely see.

Just as long as she ignored the pull in her pocket where the compass tried to drag her down. It must be broken too, she told herself, the magnets somehow mangled when the boat slammed the shore, because as they boarded the tram she had checked it, just to be sure. She had stood at the edge of the dock and gazed out at the Atlantic, knowing the sea was meant to be East. The arrow had dithered, stuttering like a lip before tears. And then it had fallen down. South. The sea spreading off the bottom of Ireland and away.

So Ruth smiled a little harder now, telling herself that once Tateh and his rats were rich and famous he would buy her a new one that worked, the four points back where they belonged again.

* * * *

In the end, the smiles turned out to be more like a plague. A transatlantic epidemic.

They were only in the immigration office five minutes before the laughter caught on, the flat-capped men behind the giant oak counter in stitches at the Ratman’s wit.

“New York?” they screeched as they regarded the stranger with his scrap of a hat and his bush of a beard—a nest for the seagulls who squawked outside, taking the Mick themselves. “America?”

His face turned as pale as the tiny patch of white on the crown of his head. Or as white as a spot on a map that desperate fingers have pointed at again and again and again. Until it is gone.

In time, so many stories would be spooled out of that moment it would become impossible to count.

Some said that when their boat found land there had been cries of “Cork! Cork!” but that in their exhaustion they heard “New York! New York!” instead; didn’t notice the difference for weeks.

Others claimed they had somehow known the English word for pork and thought that that was what the sailors were heckling—“Pork! Pork!”—a barrage of unkosher threats to run them off the ship.

Other times it was just that the captain had told them this was the last stop, “only up the road” from America; only a short, final shimmy in the wilderness—sure, they would be there in time for tea.

But for Ruth and her family, there was only one story; one version of the heartache.

After two weeks they sent Tateh off again, this time to the housing office on Lynch’s Quay, to try to find them somewhere to stay. Mame insisted it was just a temporary measure, just a matter of pride—anything to get them out of that shed. “We may be your family, Moshe, but we are not your rats.”

So the paperwork shoved them off toward an abandoned redbrick terrace, the houses huddled together like a crowd trying for warmth. “Hibernian Buildings,” they were called. Celtic Crescent. Monarea Terrace. Down the road from the port, as if the family could still be called up for the second leg of their journey at any moment.

They scalded the place with boiling water every day for a week, to annihilate the native germs. Mame refused to unpack a thing, insisting the bundles remain untouched. “Temporary, remember—what did I tell you?” But soon Tateh put up a mezuzah outside the front door, another matter of pride. Then he coaxed the girls to unwrap a couple of items they had lugged halfway across the globe (or, as it turned out, only a quarter of the way). So now there was a tub of tea leaves in the kitchen, a snag of lace around the window, a copy of Shakespeare and the Talmud sitting on the shelf, the latter with the words of different rabbis written side by side.

And every Friday as Ruth sat side by side with her family for dinner, she could almost forget about everything else; could almost ignore the rage and the resentment that lay ahead that evening as soon as she and Esther had been banished to bed.

Because they had become nightly by now, her parents’ arguments—rituals forming even in the worst of times. It went food then prayers then pleas and regrets; the high pitch of her father’s optimism and the lash of her mother’s anger reaching up the stairs to the landing, where Ruth sat, crouched in her nightdress, a covert Jewish playwright in the highest stalls of a gilded Moscow theater.

She cracked her knuckles one by one. The fourth one wouldn’t give.

“But Moshe, I have told you,” she heard her mother cry now, the line almost on cue. “We do not belong in this place.”

She spied the back of Mame’s head, the neck tensed into bones, before it thrust itself forward for the usual swerve—the same old new line of attack. “And what about Dovid?”

“Nu, what about Dovid?”

“Moshe, he is over there all by himself.”

“Austèja, why must I keep telling you it does not matter about my brother Dovid?”

It was the only time Ruth heard her father raise his voice. It sounded like a stranger’s sound.

She checked behind to the bedroom door, though she knew Esther wouldn’t stir. Even during the day her sister barely bothered to listen, unwavering in her allegiances: “How am I supposed to become a famous actress,” she had sobbed, “in some country I’ve never even heard of?”

“But Esther,” Ruth had tried to console her, eager to please as ever, “I think they speak English here too.” Because she had heard them out in the street, all right, the melody in their talk; the bounce and skip to their tone; the word “boy” after every lovely line.

“Look, my dear.” Downstairs now, Tateh was panting as if he had been running, the heat of it steaming the inside of his specs. They said he was practically blind and yet still he was able to see things that no one else could. “My darling Austèja, I will do it—I will write another play.” As he spoke he took a step closer to his wife. He seemed calmer in her orbit. “Not the rats, but a new one. I am telling you, there is something . . . I can feel it already.” He had even inquired already after one of those newfangled typewriter contraptions—just the thing to set him off. “Nu, can you imagine it,” he had exclaimed. “Letters flying through the air! Only, they do say that sometimes the letters get stuck . . .”

Lttrs flyingthrough thea ir!

And Ruth smiled now as she thought of it, because it sounded a bit like her own words; how they sometimes congealed whenever she got nervous.

Wehaveeachotheristhatnotenough?

MamewhatistheIrishwordforhome?

Doesthesecondchildalwaysgetlovedsecondbest?

“Just . . . just let me do this,” Tateh concluded now. “Let me do it for you?” Until it came, the highlight of the ritual. “For my Princess of the Bees?” The silly pet name and the only story in the world the playwright refused to tell.

His daughters had pleaded with him over the years, begging for even the gist of the tale:

“Tateh, why do you always call her that?”

“What are the bees?”

“Mame?”

But even Esther had failed to prize the truth from their mother’s lips, so instead they could only wonder at the flicker in her stone-black eyes whenever it was mentioned—somewhere between a warning and a delight. Sometimes, recently, the only sign of life that was left.

The Princess of the Bees.

Through the silence below, the footsteps clipped away.

Ruth turned and sprinted back to bed before she was caught and smacked to sleep, a hot face on a cold pillow. Only, as she lay there, she realized that tonight had been different. Because this time, Mame hadn’t objected—hadn’t said no, in any language—the ritual evolved and witnessed by two different-colored eyes.

And Ruth remembered how Tateh once told her that bees sometimes communicated not by sound, but by sight; by watching one another dance—a “waggle” he called it—making shapes with their flight that could be turned into maps for the others to follow. So then, no matter what, the rest of the hive would never get lost.

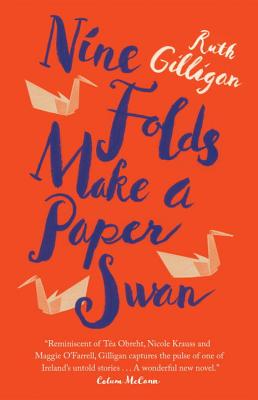

From NINE FOLDS MAKE A PAPER SWAN. Used with permission of Tin House Books. Copyright © 2017 by Ruth Gilligan.