I did not grow up in a household that discussed art. My family did not go to art museums and no coffee table books filled with the work of Impressionists or abstract artists adorned our tables. What little I learned about famous artists and techniques in my youth, I learned in art class in public school. My people were working class, living in a flyover state, and while we liked to beautify our homes, no one would consider the framed prints from Kmart or the tapestries my grandmother sewed high art.

As an adult, as I met people who’d grown up differently than I had, began working at newspapers and reading more widely, and moved to more cosmopolitan cities, I was more exposed to art and artists and the idea of high culture. But for me, so much of the construct of art museums, and the art world, seems to be built around the value of exclusion.

From the price point to get into a museum, to the fact that galleries often did not list the prices of the work or share how one purchases art, to the way people would fawn over a work of art that to me seemed nothing more than a plain line painted across a canvas, to how white the audiences at exhibits were, to how those exhibits almost never featured artists who looked like me or art that reflected my world, I always felt that so much of the “art world” existed to reinforce hierarchies.

Still, art has always compelled me. Even as I rejected the hierarchies of this world, I was drawn to beautiful works of art, whether in books, in exhibits, or on the murals in my low-income Black neighborhoods. I was particularly entranced by protest art, art by Black artists, and art by Black artists depicting the Black experience.

Slowly, I began to purchase art, first in Black countries abroad where I felt more comfortable asking about price and selecting art not because someone said the artist mattered, but because it pleased me, and then at small Black art fairs in the United States, and then, eventually, from more established Black artists, many of whom I found on Instagram. Those artists referred to me as a collector, but I have always felt self-conscious about that term. Even as my own personal collection grows, I consider myself an unsophisticated collector, one who is not particularly knowledgeable about the art world or about artistic techniques, but who collects because I am deeply moved by art.

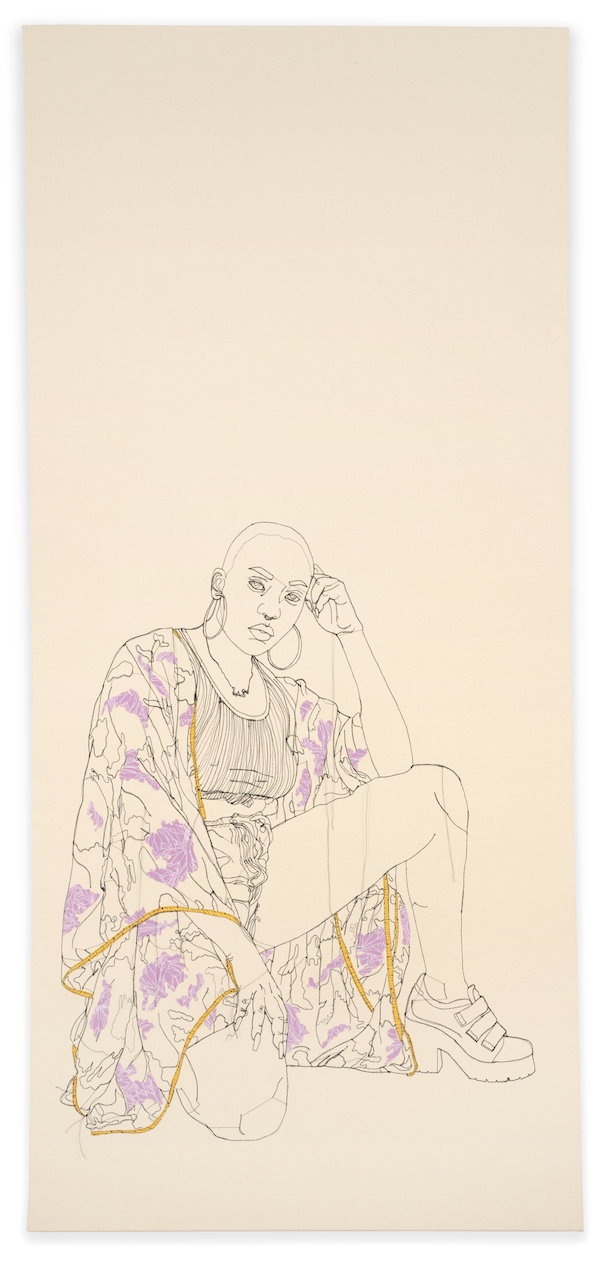

And that is why Gio Swaby’s art speaks so intensely to me. Instead of reinforcing the outsiderness of a Black girl from working-class roots who did not grow up immersed in high art or high culture, it immediately invited me in. Gio’s choice of medium evokes the seamstresses in my own family and the long tradition of quilting in Black communities, of working people who found scraps of leftover fabrics and exquisitely stitched them together into something both beautiful and useful. Gio’s chosen subjects, whether rendered in silhouette or outline, evoke the women who nurtured me, who befriended me, who surround me still. Gio’s work evokes at once awe and comfort, complexity in a misleadingly simplistic form. It is approachable even as you must pause and admire the sheer artistry, grace, and skill that created it.

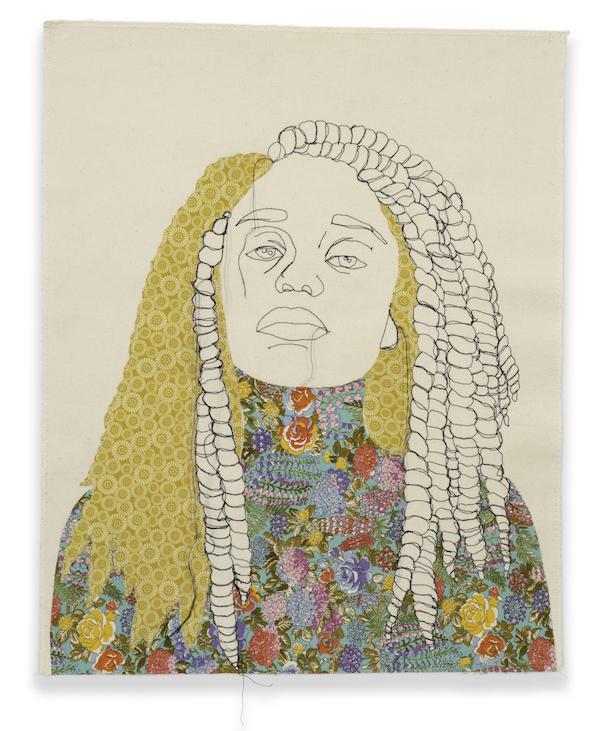

My Hands Are Clean 4, 2017, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Collection of Claire Oliver & Ian Rubinstein.

My Hands Are Clean 4, 2017, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Collection of Claire Oliver & Ian Rubinstein.

As soon as I saw it, I knew two things immediately. First, I had to do everything in my power to add Gio’s work to my collection. Second, I had to meet this brilliant woman for myself to discuss how she came to create such magnificent works. I am still working on one of these goals. The following is the fruit of the second.

*

Nikole Hannah-Jones: How would you describe your art and the work that you do?

Gio Swaby: I would describe my work first and foremost as an act of love. That’s a guiding principle of my practice, to approach from love. It is also about gratitude—expressing gratitude for the Black women closest to me in my life, and also for that greater network of Black women globally from whom I feel like I’ve learned so much about myself and how I choose to navigate my life. The textile portraits I create are about immortalizing the women I am representing. They are my attempt toward decolonizing portraiture. For me, these physical pieces are not necessarily the work itself. The work is more making connections and growing love. Those portraits are like a dedication to that work, or a residue of that work.

“I feel a sisterhood with so many women I’ve known my entire life, just for a year, or sometimes even just for a minute of having an exchange.”NHJ: There’s so much in there that I want to unpack. You talked about the women you represent. Who are these women? Who are you speaking of?

GS: Most of the people that I represent are my family and friends, people that I know personally. That felt natural to me because I just have so much love and so much appreciation for them, and my practice felt like a perfect avenue for me to express that. But also, there’s a layer that thinks about representation. Even though the work isn’t representative of this specific Black woman or Black girl viewer, they can still see themselves reflected.

This idea of representation reflects what I’m trying to say about love, when I say I’m expressing it on a more personal level and also on a larger scale. It’s very personal, but I want to maintain that connection with a larger community and make sure that there’s reciprocity between the work itself, me as the maker, and also the people who will view the work. And when I say the people who will be the work, I’m specifically talking about Black people and especially Black people of marginalized genders.

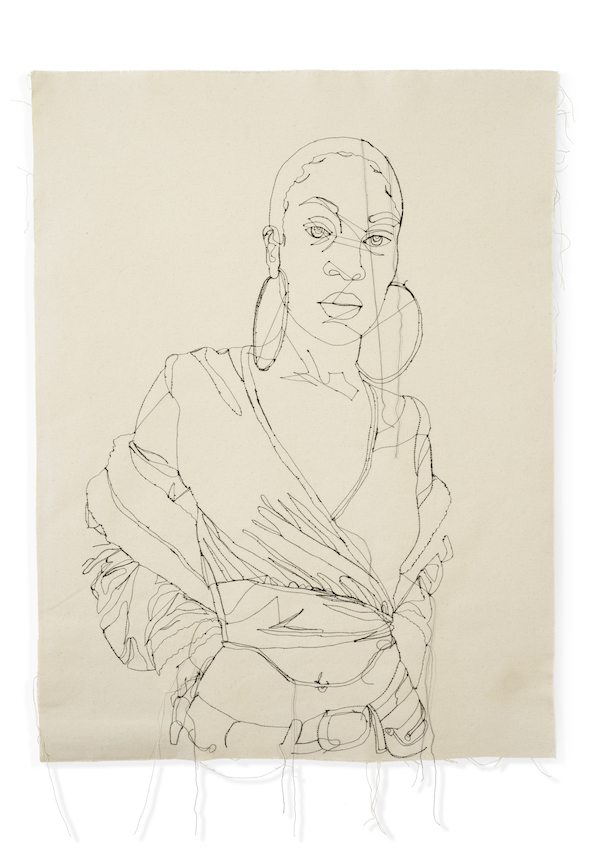

Another Side to Me 4, 2020, Thread sewn on canvas, Collection of Jason Reynolds

Another Side to Me 4, 2020, Thread sewn on canvas, Collection of Jason Reynolds

NHJ: Who are these women on a more personal level, the women you know in your life? What do they represent to you about your life, your community, and also Black women?

GS: They partially represent an important aspect of my practice, which is balance— being able to show that strength and vulnerability, the strong and the soft, and being able to find a place in between that is sustainable. They also represent the sisterhood that we have cultivated. I feel a sisterhood with so many women I’ve known my entire life, just for a year, or sometimes even just for a minute of having an exchange.

These works are representative of the sisterhood that we have built together as Black women, a support system for one another. When I think about it on a personal level, there’s a journey that I’ve come through of learning to love myself. I think I will always be on this journey of unlearning and relearning. I’ve internalized so much of what I now recognize as a perpetuation of white supremacy and replaced it with personal practices that are rooted in anticolonialism, love, and care.

NHJ: What were some of those messages that you have been working to undo?

GS: Something that comes to mind immediately is rest and joy are a big part of my life, and I am working toward being intentional about finding rest, and also being intentional about finding and creating joy. That’s a complex and difficult kind of thing to navigate, especially for Black people, when we think about our histories and what we have to deal with on a daily basis because so many systems are in place that want to keep us kind of inundated with work. We don’t have time to reflect.

“I actually want to celebrate that work that often goes unappreciated and unrecognized, like so many parts of womanhood, and that’s why I choose to represent women.”NHJ: You talked about wanting to decolonize portraiture. Can you explain what that means to you, and how your work tries to subvert that?

GS: Oh, yes. I just want to start out by saying that I don’t even know if it is possible to decolonize portraiture, but it’s important for me to take those steps toward attempting to do that work, to try to find out. Is it necessary to completely rebuild this thing and start from a new place? Or can I work within existing systems? The landscape is constantly moving and changing. How do I approach that? So much of the art we’ve seen of Black people, historically, has not been made by Black people. It shows so much suffering and trauma, and I think that seeing ourselves represented like that has a strong negative effect on our mental and emotional health, because we see a version of ourselves reflected in those images.

What I’m trying to do is use my practice to combat those images, to create representations that are nuanced and maintain the agency of the sitter. This is a contribution to an ongoing conversation continued by artists like Bisa Butler, Ebony Patterson, and Kehinde Wiley. I’m approaching my practice as an attempt to decolonize portraiture in a way that subverts, or often outright rejects those images that show us at our lowest moments.

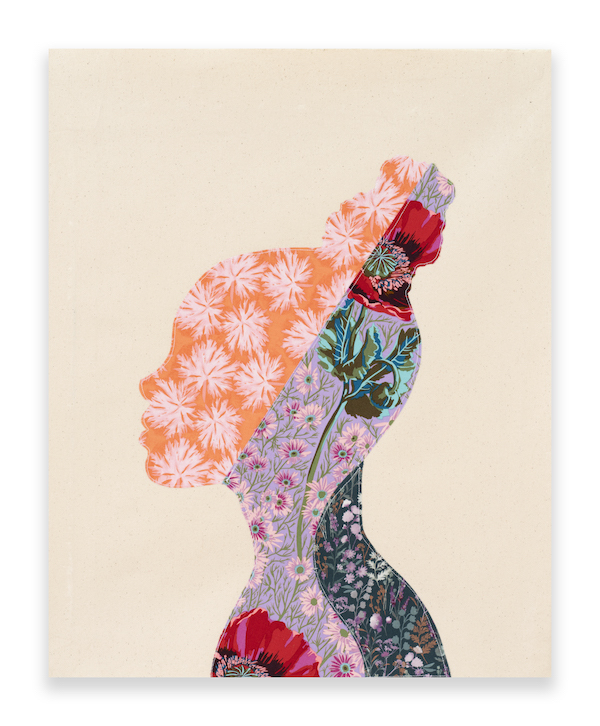

New Growth Second Chapter 11, 2021, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Collection of The Altman Family

New Growth Second Chapter 11, 2021, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Collection of The Altman Family

NHJ: And your art, at least as far as I know, is only women, right? Talk to me about that decision.

GS: This is another decision that just felt natural. My mother was a single mother, and although my father was a part of my life, I grew up mostly within the influence of my mother and older sisters. My family has a very matriarchal structure. I feel like I was raised by my grandmother, my sisters, my aunts, my mother—all Black women.

So, I’ve always looked to them for guidance, for strength, for support. Because a key focus of my practice is to show gratitude and express love, it feels natural to place Black women at the center of that. I work mostly with textiles through augmented forms of quilting and embroidery—which is historically considered to be women’s work.

I make a specific choice not to reject that connection to domesticity. I actually want to celebrate that work that often goes unappreciated and unrecognized, like so many parts of womanhood, and that’s why I choose to represent women. I also want to make it clear that when I say women, I mean trans women, queer women, and not just cishet women.

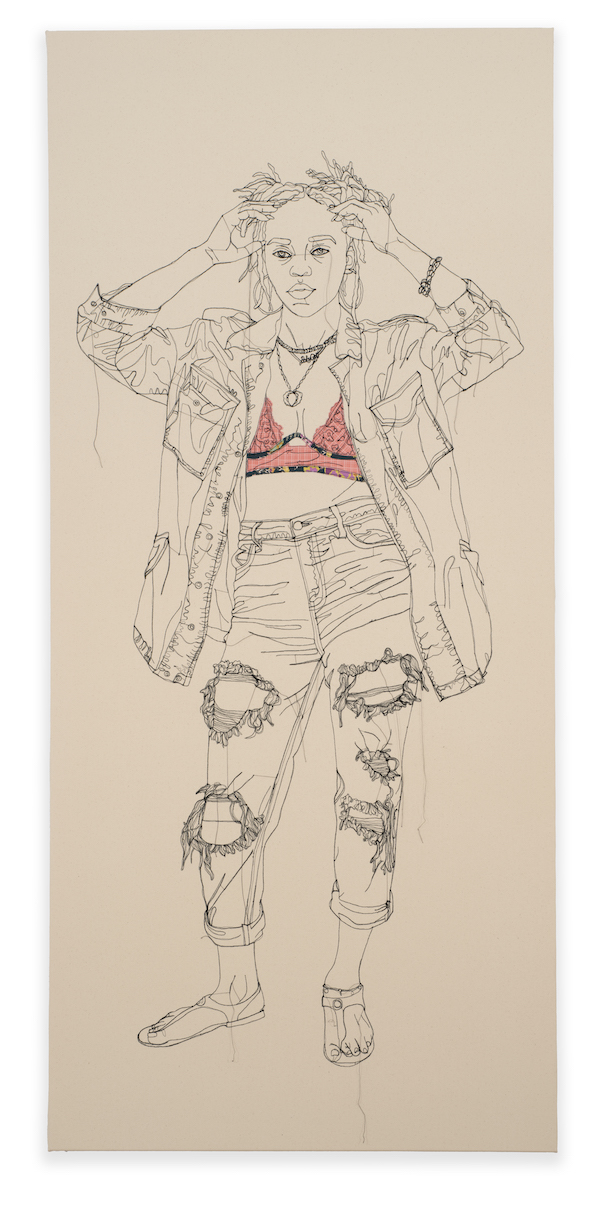

Pretty Pretty 8, 2021, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Museum purchase in honor of James G. Sweeny

Pretty Pretty 8, 2021, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Museum purchase in honor of James G. Sweeny

NHJ: So, let’s talk a little bit about biography. When I finally got to meet you, the woman whose artistry I have much admired, in Brooklyn a few weeks ago, we talked about how I think about art as a kind of novice collector, and how I imagine that part of the decolonization process is about taking something that often, at least in my experience as a Black woman from a working-class-background home, has felt very exclusionary.

And certainly, I always felt that art galleries were exclusive, and, sometimes, as if there was some joke being played that people like me were not supposed to get. And we talked about when you go into a space and you see something and it appears to me, or a person like myself, to be a line on a paper, but you are told it is a profound piece of work. If you do not feel that way, somehow it’s because you’re not smart enough or cosmopolitan enough.

So, I’d like to talk about this as clearly part of what you’re doing when you talk about decolonizing. You are featuring regular Black women and regular Black girls and you’re using a medium that has been kind of looked down upon as not really fine art or high art. So, I would love to have you talk about your journey. You are a traditionally trained artist, in that you’ve gone to art school, but you’re producing art that to me brings in our community and people coming from a textiles background and using a medium that you grew up with.

I would love for you to talk about when you started to conceptualize yourself as an artist and what your first exposure to art was. How was the art you were exposed to different from what you were being taught was art?

GS: I like that question a lot, because I was not exposed to art throughout my life. Nobody in my family was what is considered to be a professional artist. When I decided to start my journey toward becoming an artist, I had never been to a gallery. I didn’t even know about an art community in the Bahamas. So, I come from that place of not knowing. There are people who have maybe grown up going to art galleries, but that’s often not the case for a lot of Black folks.

Pretty Pretty 9, 2021, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago, Barbara E. and Richard J. Franke Endowment Fund

Pretty Pretty 9, 2021, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago, Barbara E. and Richard J. Franke Endowment Fund

My first exposure was in college. Being from the Caribbean, we are already placed on the outskirts of the art world. So, I was already approaching art from the place of being othered by an international art community. In this sense, I’ve always approached art from the outside. Being born and raised in Bahamas, you are taught to be adaptive, to work with what you have. You might not have easy access to oil paints or the biggest canvas or these super fancy art materials or much of what would be considered to be real art objects. But we still made art.

We used house paint or whatever we had access to at that moment, and I think that’s how I arrived at this place in my practice. It’s so much a part of who I am and where I come from.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Gio Swaby, published by Rizzoli Electa. Top image credit: New Growth 2 (triptych), 2021, Thread and fabric sewn on canvas, Collection of Rasheed Newson and Jonathan Ruane