CAROL

1933

Finally the weekend came and it was time to go. They didn’t speak much in the truck. The basket of things that sat between them trembled with the motion of their journey. Carol had wanted to bring Mary Bright, but her father said it was time to give up childish things.

When they pulled up to the white farmhouse, an old sheepdog rose from his place in the shade. The yard had some patches of yellow grass, but it was mostly dirt dotted with chickens and a few mossy trees.

That’s Russ, Travis Curt said. Good ol’ dog. He won’t hurt you.

The animal followed them inside the house, its tail sweeping back and forth.

I usually got chores on a Friday, Carol. But I took the day off workin’ so’s we could spend time together.

There was furniture, but it seemed very old and the sofa was losing its insides. In the main room was a fireplace with soot stains up the wall and logs left over from a cold spring. The whole place was dusty and smelled like old shoes.

Travis stood in the hallway, looking from room to room, holding the basket of girl’s clothes.

Why don’t you go out on the porch with Russ. I’ll put this down somewhere and bring you sweet tea.

Without speaking, Carol turned and went back outside, choosing to sit in the very middle of the bench seat. The dog rushed forward and began shouldering his body into her legs. Carol reached down and stroked one of his ears. But it wasn’t enough, and he kept moving his head around under her hand.

When Travis appeared, Carol took the glass and drank the sugary liquid in a few gulps.

I can get more if you’d like.

I’m fine.

When she didn’t slide over, he leaned back against the wooden rail.

Carol was now moving her hand up and down the dog’s coat, even letting it disappear into the fur where she could feel the shape of his bones.

Travis watched the whole thing, sipping on his drink.

You lived with your daddy a long time? he asked, finally.

My whole life. Where your folks at?

They out back… he said, pointing with his glass. Buried under the peach tree.

Travis put his drink down and pinched some tobacco from a round tin, which he stuffed into his gum. When you’re ready to start cooking I’ll show you the kitchen. I’ll bet it’s more’n what you got now with your daddy.

*

Carol spent Friday afternoon preparing things for a meal. There were so many cans she couldn’t decide what would go best with the animal Travis intended to slaughter. And it was hard to move around the kitchen with Russ under her the whole time, his tail swinging wildly.

In the end, Carol made biscuits, beans, and corn to go with the chicken.

At the table, she chewed her portion slowly and looked at the green and white tile Poor. Everything was different at Travis Curt’s. Even the white supper plates were painted with green grapes and vines, as though somebody had planned for everything in the house to have something in common.

When Travis cut into his chicken it was raw on the inside. He picked it off the plate with his fingers and gave it to Russ, who chomped the meat hurriedly with his mouth open. Travis had killed and plucked the bird that afternoon on the porch. Carol watched through a screen door, wearing an apron Travis said once belonged to his mother.

I can’t believe how good these biscuits are, Carol. He held one up. Russ’s eyes widened and he made a noise. How’d you make ’em?

My momma taught me.

Where she at?

Carol glared at him. In heaven with your folks I expect, lookin’ down on us this very minute.

Travis coughed and put the biscuit down. Russ made a noise too, then slumped back under the table.

Your daddy said you could hardly do nothing, but this food ain’t half bad. I’m much obliged.

*

After the meal, they sat on the porch as the sun lingered low on the horizon, not realizing it was already night under the trees. Travis went inside and came back with two peaches he had rinsed in a bucket.

We’re about like my own parents was, sitting out here, Carol. Ain’t that something? How’s your room? I made it pink, which as you know is a woman’s color. When Travis laughed, the flesh under his chin moved up and down, reminding Carol of the chicken that had sat in his arms like a small cushion, turning and tilting its head moments before he wrung its neck.

That bed I give you was the one I got borned in—if you can believe that. And the one Momma died in, too.

Carol’s mouth twisted with disgust. I can’t sleep in no dead person’s bed.

It’s clean, Travis insisted. No one’s slept in it for goin’ on twenty years.

I ain’t never slept where someone died, Carol said. That’s all.

You afraid of ghosts or something?

Carol didn’t answer.

Russ was on the top porch step, his head down on two front paws.

Well now, Travis said, tossing his peach pit into the darkness. You could always sleep somewhere else if you’re afraid.

I ain’t afraid, Carol said sharply. It’s just somethin’ I’m not used to is all.

But that first night she slept on the Poor, not wanting to touch any of the dead woman’s things.

*

Carol kept busy on Saturday, moving from room to room sweeping, mopping, and wiping away the dirt from years of silence. She wanted to sing but wouldn’t allow herself. Travis came in from time to time for glasses of water, and would praise how good a job she was doing. It was very hot, even with the windows open, and whenever Carol sat down to catch her breath, she would hear little steps and then from around the open door a small face would appear.

That night Carol was so tired she slept in the bed, but stayed in her clothes, watching the door as long as she could—waiting for the handle to turn by itself.

On Sunday morning they were back on the porch with mugs of black coffee, watching the chickens peck and raise dust with their sharp feet. When Travis spat tobacco juice into the yard, some of them jumped back.

That was where Momma used to sit, Carol. Right where you are now.

Carol shuffled around, as if to dislodge the image balanced in Travis Curt’s mind.

Beyond the porch, a honeysuckle bush roped up one side of the house. Carol could taste its flowers in her nose and mouth like tiny, melted secrets. There were no holes in Travis’s porch, no wet wood that had been left to rot.

He told Carol that his parents had died a few weeks apart in the flu epidemic when he was thirteen himself. He asked if it was Pu what killed Carol’s momma, but she didn’t know.

By the time my folks passed, he went on, I knew all there was to know about cropping. Never went to school like some kids now ’cause I never had no use for book learning.

When he drove her back Sunday night in his pickup, her clothes smelled like cooked food and her hands were dried out from the soap powder she’d used to scrub his underwear and socks on a wooden board. They didn’t talk and passed only a few other cars. When they hit a hole in the road, Travis’s knee knocked into Carol’s leg and she jerked back like one of the chickens in his yard. Then she opened her window and spat into the rushing air.

When she got home, it was completely dark. Her father was just a shadow on the porch, but she could smell the liquor like a heavy, dumb perfume.

I bet you had yerself a good ol’ time, he said. If you’re anything like your mother was.

Carol passed without a word. All she cared about was getting upstairs to where Mary Bright had been waiting, unable to see or touch or feel without Carol. Now they would stay up, as Carol told her everything there was to know about dogs.

Early next morning Carol dressed in the wash of dawn light. Then she took her doll and the yellow tablecloth out to that clearing in the woods, where memories of her mother gave her hope that life would not go on forever in the same way. In that green place on the special cloth, ringed by trees and loose ribbons of birdsong, Carol imagined herself and Mary Bright escaping on Russ’s shaggy back, guided by fairies and sprites from the picture she kept in her pillow.

She stayed there until the day’s color began to fade. Then she returned to her daddy’s house with hunger clawing at her insides.

*

The next weekend, Travis was proud to show her a radio he’d bought. Now, he promised, she could listen to country music any time she pleased. But all Carol wanted was to pull Russ up into her arms. For the rest of the day he followed her everywhere, as if attached by a length of invisible cord.

In the evening Carol served dinner on the plates with green grapes and vines. Travis sat at the table studying his hands, which were sore and swollen from digging trenches in the dry field.

I’m not surprised that apron fits you so well, he said without looking up. Not surprised one bit.

Carol smoothed the front where his mother, long ago, had stitched a strawberry into the fabric. After supper, Travis told her to sit out on the porch while he wiped the dishes clean. Carol said no, but he insisted. It’s what my own papa would do sometimes, when Mama was t’ard from cookin’.

When he had finished, Carol heard the screen door open and there he was, red in the face and with sweat running down his neck. He sat next to Carol, but they hardly spoke. Light was draining quickly from the world they shared.

Sometime later, Carol left the porch and went up to bed without saying anything. Russ tried to follow, but Travis held him back, listening as she disappeared through the screen door and then trudged barefoot up the stairs.

An hour later, Carol was in bed when she heard a creak and saw the handle turning. He was whispering her name over and over from the doorway. She was so afraid that all she could do was pretend to be annoyed.

What is it? she hissed. I’m sleeping.

Do you need anything?

No, I do not.

Glass of water?

I’m fine.

Then she heard him creep closer. You mind if I stay awhile? I’ll just sit on the end of the bed if it don’t bother you.

Carol pulled the blanket up to her chin.

It’s your house, she said. Sit where you want.

Earlier that day, Carol had wondered if she might come to Travis Curt’s house more often. The look on Russ’s face when she left was too much.

Now the shame of that wish was cutting her small heart into pieces, as if to devour it.

The bed tilted with his weight. Carol thought about the dog outside in the yard, asleep under a tree, dreaming of plate scraps. She tried to picture his long nose, and those gray hairs that came off in her hand when she touched it.

When a fan of moon appeared in her window, Carol felt the covers moving backwards like a slow, unstoppable tide.

He was speaking again, but too quietly for the words to rise above the creaking springs. Then she felt a hot weight on top of her, droplets of sweat that were not her own, and the whites of his eyes, slick and veined.

She pushed back on his meaty shoulders, but it was like a stone, grinding out the air from her lungs. Then a sudden tearing pain at the top of her legs, and a wetness she knew was blood. For a few moments it was like a barbed hook, ripping out her insides. She couldn’t breathe. Splinters on his cheek tore at her face. It was like being murdered, she thought, except somehow part of you was still alive.

When he was done, Travis Curt got up and went out of the room, pulling the door closed behind him. Carol could hear him outside on the porch sucking down mouthfuls of night air. The unblinking moon was in its final descent over the house, like God looking down. Watching her. Watching them all.

__________________________________

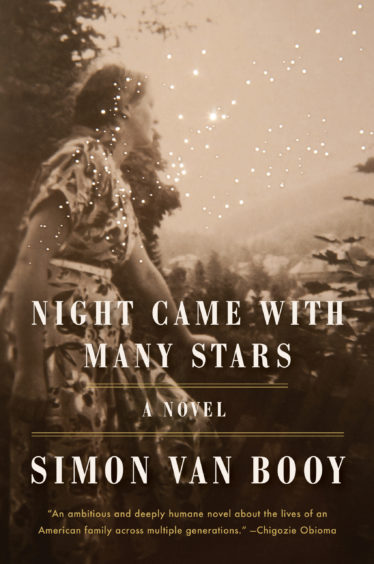

Excerpted from Night Came with Many Stars by Simon Van Booy. Excerpted with the permission of David R. Godine Publisher. Copyright © 2021 by Simon Van Booy.