Nicole Chung: "Adoptees Have So Rarely Gotten To Tell Their Own Stories."

The Author of All You Can Ever Know in Conversation with Mira Jacob

Sometimes, you get so taken with a book, it unhinges you a little. You watch the way an author shapes a scene, her sure steps across uneasy territory, and realize you are as inspired as you are desperate to keep reading.

Nicole Chung’s All You Can Ever Know became that book for me last summer, as I finished up my own graphic memoir on race in America. A dexterous telling of her transracial adoption by white American parents, and later reconnection with her Korean American birth family, the book crackles with issues of identity, race, belonging, and what it means to look directly at the aspects of your life you’ve been told to ignore.

It’s a stunning read at any time, and especially in the charged months I was finishing up a memoir, a godsend. Any writer familiar with writing about family will be well acquainted with the landmines of overwriting, underwriting, or just plain not writing out of fear, guilt and love. How extraordinary it was, then, to read scene after scene of Chung’s deliberate and fearless prose. Peering into territory Americans like to keep in soft focus (see: adoption as a redemption story; interracial families as a love-conquers-all utopia), she carves out a space clear of assumption, wishful thinking, and best intentions. The result, surprisingly, is a boldly loving portrait of the complex set of relationships we call “family.” I caught up with Nicole right before the book launched.

–Mira Jacob

*

Mira Jacob: One of the things I kept thinking when I was reading All You Can Ever Know is how emotionally precise your writing is. When you write about coming to understand that you have a right to know your birth family, even if doing so hurts the parents that raised you, you do it with a calm, unsentimental gaze. It made me wonder: did you have that clarity before you even started, or did it emerge in the writing?

Nicole Chung: It took me so long to actually decide to search. I’d looked into the process, I’d asked questions of people, but I just was not emotionally ready to move forward and actually search. By the time I got there, I did feel a strong sense of rightness and purpose, despite all my anxiety. I never truly felt like I had a “right” to know my birth family—I still don’t—though eventually, I felt I had a right to search for them, and for the part of my own history that was missing. I always knew they could tell me they didn’t want to talk to me, and while that would have been so difficult, I also wanted them to have that choice. That’s partly why it was so scary to reach out to them—their lives had gone on without me, and they could easily have said no.

I definitely was concerned about hurting the parents who’d raised me. I didn’t tell them about the search until I’d made up my own mind. I had gotten to a point where not knowing anything, not even trying to learn, was no longer bearable. And I was, to be honest, weary of trying to live up to other people’s expectations of what a “good adoptee” was. I strongly felt I needed my history, and medical information, and (if I was lucky) answers to these questions I’d had for as long as I could remember—I hoped my adoptive parents would understand all of this, and I think they did.

MJ: The pressure you felt to perform a happy assimilation is not unlike what America expects of its immigrants. Why do you think we are asked to lean so hard into this fantasy of everyone being the same, deep down?

NC: In my case, I know my family was explicitly told—by social workers, by the judge who finalized my adoption—that they should ignore my race. The word they used, according to my mom, was “assimilate”: “Just assimilate her into your family and everything will be fine.”

So by the time I got to the stage where I could recognize our most obvious differences and ask about them, my parents had already had years to get used to the fantasy that my race was irrelevant. And in raising me in such a way, and saying things like “we wouldn’t have cared if you were black or white or polka-dotted,” they were mostly just following all the advice they’d been given, by people they believed to be experts in adoption. I also think it’s what they wanted to believe! To them, I was not the daughter of Koreans or the daughter of immigrants or their Asian daughter; I was just their daughter.

I honestly believe my race was irrelevant, to them. But it obviously wasn’t to me, or to many other people. And when I started to realize just how much it mattered, because I was getting called names at school, I did not even have the words “race” or “racism” to use. We had just never used these words, or even really acknowledged them.

As for being expected to be “thankful,” and perform that—I did feel that pressure. Not so much from my parents, who always told me they were the fortunate ones to have been able to adopt me; more from other people. People will say the strangest things to adopted kids. They will imply or say outright that our parents are saviors, that we should feel grateful to be here. My personal favorite was when a teacher told me I was lucky to be raised here, “in a country where girls and women are truly respected” (not knowing I was born in Seattle and would’ve been raised “here,” anyway).

“I had gotten to a point where not knowing anything, not even trying to learn, was no longer bearable. And I was, to be honest, weary of trying to live up to other people’s expectations of what a “good adoptee” was.”

MJ: Oh my god, that line. The old standby of Americans everywhere—said by men who have never done a thing to advance women’s rights here, and the women who conveniently ignore them!

The depth of your parents love for you is so clear on the page—I’m thinking specifically about when had to call your mother in the middle of the night when you were pregnant so she could help you remember who you are. I love how whole and nuanced and complicated you let that scene be. It made me wonder, at what point did you know you needed to write this book?

NC: My answer to this question changes all the time. Sometimes I say “childhood,” because that’s how long I’ve been answering questions and talking with people about adoption, though the specific known narrative details and my own feelings about my adoption have changed over the years. Certainly I wrote this book in part because I wished I had one like it when I was growing up adopted. But I think I only seriously began to consider writing this book, covering this particular ground, three or four years ago.

MJ: What made it possible for you then?

NC: I started publishing personal essays about adoption. I wrote about other things, too, but it was there in the mix. I think I began to find more community as a result, and I began to understand that this was not some niche interest or experience that only mattered to people who grew up in families like mine—a lot of people were interested; a lot of people could relate; a lot of people had questions. And I felt like I was only going to get to tell the whole story (as complicated as it was) and do justice to it in a full-length book.

MJ: Was that overwhelming at all? Gratifying?

NC: It was gratifying, yes—of course, no one had told me about trolls, so as I published those first essays I was learning about that side of things as well. But I loved (and still love) hearing from people who connect to my work, or find it worthwhile.

I’d been telling some version of my adoption story my whole life, but it was powerful to do so without censoring myself—to talk and write about it on my own terms. It was gratifying, but it was a bit scary, too.

MJ: Wait—I know you get a lot of grief for writing as a woman of color with opinions (god forbid), but trolled specifically for pieces on adoption? Why?

NC: I remember I got trolled for weeks after I wrote this essay for The Toast. Any time I write about racism, I know I’ll get some sort of pushback from white people, and it’s been worse than ever since the election.

Sometimes an adoption piece will strike a nerve with people who think that sharing my own reality means I’m condemning the entire practice of transracial adoption (which, to be clear, I have never done). Some white people like to tell me that talking and writing about race at all makes me part of the problem. Not long ago, someone sent me what I can only describe as a lecture in email form, all of it built on the assumption that I must not love my adoptive family or my country.

Adoption narratives, historically, really have not focused on adoptees. We’ve so rarely gotten to tell our own stories. I think that’s changing, but I also think there are some people out there who feel a little threatened when we do speak up—particularly if we’re adoptees of color, talking about race and complicating the straightforward, simple adoption narrative people are used to.

MJ: Have you ever heard from a white parent in a transracial adoption?

NC: Yes, I hear from adoptive parents. Often, I get thanks; occasionally, I get criticism. Overall, I do think my writing about adoption has been read very generously by people, but of course there are always exceptions.

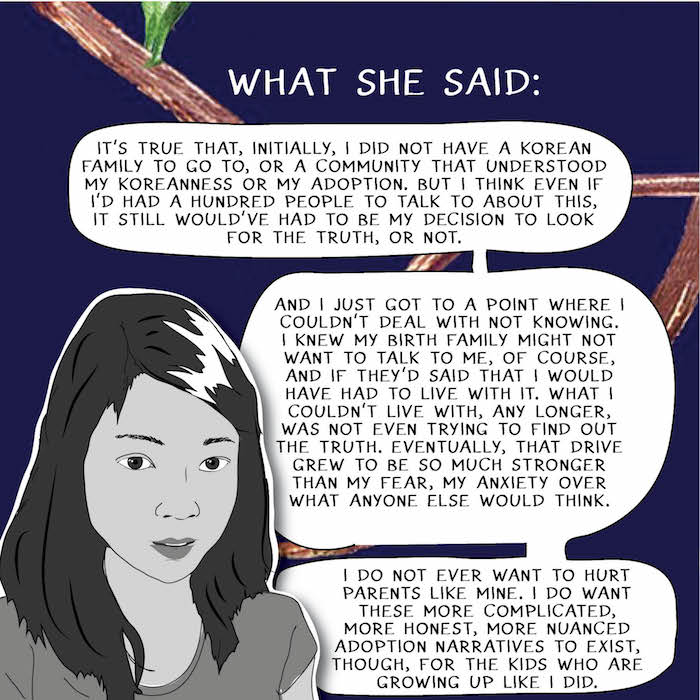

MJ: One of the things I kept being so moved by as I read All You Can Ever Know was the realization that you had to take the lead to go somewhere no one wanted you to go. You didn’t have a community backing you. You didn’t have lifelong friends who understood transracial adoption on the cellular level that you did. You just had you, and your husband’s understanding, and the risk of alienating the one stability you had known all your life. How did you find a safe place to write from?

NC: It’s true that, initially, I did not have a Korean family to go to, or a community that understood my Koreanness or my adoption. But I think even if I’d had a hundred people to talk to about this, it still would’ve had to be my decision to look for the truth, or not. And I just got to a point where I couldn’t deal with not knowing. I knew my birth family might not want to talk to me, of course, and if they’d said that I would have had to live with it. What I couldn’t live with, any longer, was not even trying to find out the truth. Eventually, that drive grew to be so much stronger than my fear, my anxiety over what anyone else would think.

I think, too, that writing about all of this has helped me find some communities I didn’t have before. I wouldn’t have guessed that would happen, but you know, it has—online, and in the real world, too, I have the Asian American community I didn’t have growing up.

I mention fellow adoptees in my Acknowledgments section because I really did think about them so often while writing this book. Every time I got scared writing it, every time I wanted to shy away from something, I’d think of the adoptees who’ve talked to me, who’ve been so open and so generous and so accepting. I’d think of adopted kids and young adults growing up without seeing any stories like theirs in literature. All of that, too, feels so much bigger and so much more important than my writing and publishing anxieties.

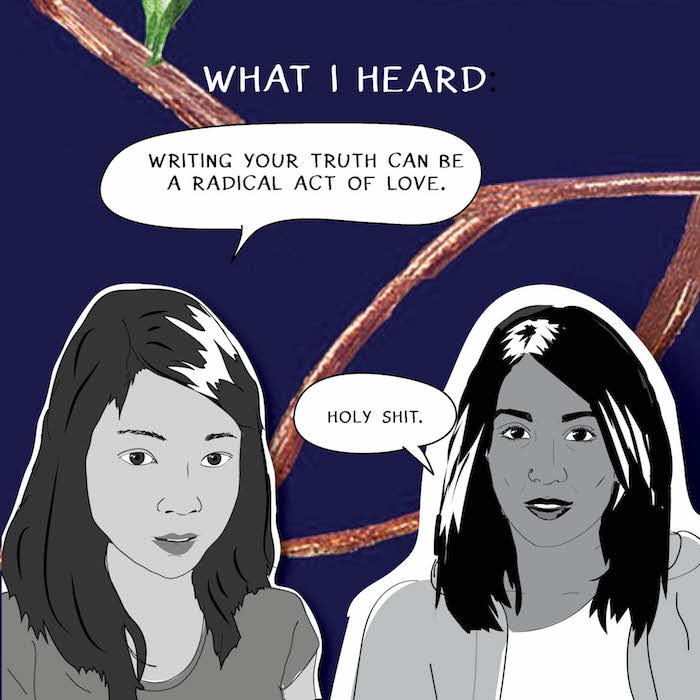

I do not ever want to hurt parents like mine. I do want these more complicated, more honest, more nuanced adoption narratives to exist, though, for the kids who are growing up like I did.

MJ: As a parent, it’s scary to realize that there are some parts of your child’s identity formation in which love alone is not enough, in which you, and your answers, are not enough. I’m curious—how do you think your search for your own identity has informed your parenting?

NC: I have a lot more information and history to share with my kids, which I’m so grateful for—that was why I wanted to search in the first place. I also think what I’ve learned has made it easier for me to talk with them about issues of race, family, identity, and belonging. And of course I can’t really compare my experience of parenting to anyone else’s—mine is all I know—but I think just being an adoptee, and one in reunion to boot, means I will never be able to take these biological connections for granted. I feel so lucky to be a parent, to get to parent my particular kids, and to have members of my birth family in my life.

“I do want these more complicated, more honest, more nuanced adoption narratives to exist, though, for the kids who are growing up like I did.”

MJ: The dedication of this book reads For Cindy and for our daughters. Can you tell me about that?

NC: Yes, of course! This book is dedicated to my sister, who only found out that I existed after I got in touch with our parents, and the kids we’ve had since we reconnected over a decade ago. She went from being a stranger to being one of the most important people in my life. Her story, our story, is at the heart of this book—I think of her as its true hero.

I wanted to include our children in the dedication because this story is really theirs, too—it’s a shared legacy. They’ve always known our family as reunited; they have always known and loved one another. I love and am so thankful for that, and someday I also want them to understand how and why and what we had to do to put this part of our family back together.

MJ: I often think we write books to learn something essential about ourselves, whether that is something personal or something we needed to figure out about our own writing process. What did you figure out in writing this book?

NC: WELL, I learned that I could write a book, and this book in particular! Which was a valuable piece of information to have. I didn’t truly know I could write the book until I had done it. I had all the pieces before I started writing—it’s not as if I was in suspense over how anything turned out—but working on it, writing it, and restructuring it did shift my understanding of my family and my adoption. I had to get readers to see these things clearly, without the benefit of knowing them as I do, and in the process, I saw them more clearly. If my adult life has been spent bringing those two very complicated things into sharper focus, this was one more click in the right direction.

MJ: So if you could go back and give the person you were when you started this book some advice going forward, what would it be?

NC: Don’t worry so much about what your parents are going to think; they’re going to love it.

(Get ready for everyone to ask you what your parents thought of it, though!)

And finally: When your brain sends you that one particularly vivid dream about how to fix your book, don’t waste a whole week hemming and hawing and questioning whether it’s going to work or be a gigantic pain in the ass—just trust your subconscious and do it. It’s going to be okay.

Mira Jacob

Mira Jacob is the author of the critically acclaimed novel, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing, which was a Barnes & Noble Discover New Writers pick, longlisted for the Brooklyn Literary Eagles Prize, and was named one of the best books of 2014 by Kirkus Reviews, the Boston Globe, Goodreads, Bustle, and The Millions. She is currently drawing and writing her graphic memoir, Good Talk: Conversations I’m Still Confused About (Random House, 2019).