Neil Gaiman on His Favorite Horror Movie

The Wonderful Dream That Is The Bride of Frankenstein

Films deliver their pleasures in different ways. Many films give you everything they have to offer the first time you see them, leaving you nothing for another viewing. Some deliver what they have grudgingly on first viewing, only to reveal their magic on subsequent occasions, when things become increasingly satisfying. Very few films are dreams, configuring and reconfiguring themselves in your mind on waking. These films, I think, you make yourself, afterwards, somewhere in the shadows in the back of your head. The Bride of Frankenstein is one of those dream-films. It exists in the culture as a unique thing, magical and odd: a lurching story sequence as ungainly and as beautiful as the monster itself, that culminates in a couple of minutes of film that have seared themselves onto the undermind of the world.

It’s a lot of people’s favorite horror film. Dammit, it’s my favorite horror film. And yet…

My daughter Maddy loves the idea of The Bride of Frankenstein: she’s ten. Last year, captivated by the little statue of Elsa Lanchester in frightwig that stands, facing a statue of Groucho Marx, on a window ledge halfway up the stairs, she decided to be the Monster’s Bride for Hallowe’en. I had to find her imagery of Karloff and his bride-to-be, email her photos of them. Several weeks ago, finding myself in sole charge of Maddy and her friend Gala, I made them hot chocolate and we watched The Bride of Frankenstein.

They enjoyed it, wriggling and squealing in all the right places. But once it was done, the girls had an identical reaction. “Is it over?” asked one. “That was weird,” said the other, flatly. They were as unsatisfied as an audience could be.

I felt vaguely guilty—I knew they would have enjoyed House—or is it Ghost?—of Frankenstein, the one with Karloff as a mad scientist, and John Carradine’s Dracula, not to mention a Lon Chaney Jr. wolfman—so much more. It’s a romp, after all. It may not be scary, but it feels like a horror film, and it would have delivered everything two ten-year-olds needed to be satisfying.

The Bride of Frankenstein doesn’t romp. It’s oneiric, a beautiful, formless sequence of silver nitrate shadows, and when it ends I wonder what happened, and then I begin to rebuild it in my head. I’ve seen it I do not know how many times since I was a boy, and I’m almost pleased to say that I still can’t quite tell you the plot. Or rather, I can tell you the plot as it goes along. And then, when it’s done, the film begins to scum over in my mind, to reconfigure like a dream does once you’ve wakened, and it all becomes much harder to explain.

The film begins with Mary Shelley, Elsa Lanchester, all sly smiles and period cleavage, talking to an intensely dull Byron and Shelley, introducing us to a sequel to the original Frankenstein story. And then it’s moments after the first film, Frankenstein, and the story starts again. The monster survived. The status quo has been restored.

Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) is getting married to the wimpy Elizabeth (Valerie Hobson). (The wimpy Elizabeth is the real bride of Frankenstein, and is, I suspect, given the film’s title, one of the main factors responsible for the confusion in the popular mind between the scientist and his monster.)

Ernest Thesiger’s Dr. Pretorius, a far madder scientist than our Henry, strides into Henry Frankenstein’s life, like a man bringing a bottle of absinthe to a reformed addict. Dr. Pretorius, waspish, camp, unforgettable, trolls in from a world much more dangerous than Henry’s. He’s sharp and funny, steals scenes, and has a marvelous sequence with bottled homunculi—lovers, a king, a priest. This has something to do with his own alchemical researches into creating life, and, I find myself thinking whenever I watch it, nothing at all to do with the film at hand. It sits in the mind like a dream, inexplicable, a moment of movie magic. I find myself fancying director James Whale as Pretorius here, the homunculi his actors, ready to lust or lecture or die as he desires.

Henry Frankenstein himself is feverish, and strangely absent from the film that bears his name, emotionally and truly. The alcoholism (and perhaps the tuberculosis) that would soon enough carry off Colin Clive is already muting his vitality. All the monsters have more life in them than Henry Frankenstein does now, and watching the film I imagine that they will live longer, once the action is over.

Karloff plays the Monster. His face is part of the strange experience of the film: we have seen many people since Karloff who have portrayed Frankenstein’s Monster, but none of them were the real thing: they looked too brutish, or too comical—Herman Munsters in waiting. Karloff is something else: sensitive, hurting, a former brute now learning language and longing and love. There is little in the monster to be frightened of.

Instead we pity him, sympathize with him, care about him.

(The sequence with the blind hermit is subject to slippage in my mind with its parody in Young Frankenstein. I worry, when I see the blind man in Bride, that he will pour hot soup on the monster, or set light to him, and am always relieved when they survive the meal unscathed. Instead, unable to see the monster, the hermit is the only one who is able to look at the monster without prejudice.)

James Whale, directing the film with elegance and panache, builds lovely catacombs. There is a terrible beauty in each perfectly composed shot, just as there is wit and poetry in William Hurlbut’s script.

Of course, it’s hard to care a twopenny fig for either Henry or Elizabeth, and I suspect that Whale knew that: from being the tragic focus of the first movie, Henry Frankenstein now becomes the film’s Zeppo, a bland lover in a cast of shambling zanies. It’s one reason why the film feels so subversive, and so deeply surreal. In Bride of Frankenstein, all is prelude to the unwrapping of Elsa Lanchester, the revelation of the true Bride, the one that the movie’s really named after. She is revealed; she hisses, screeches, is terrified, is wonderful, and once we have seen her there is nothing left for us. As Karloff’s monster realizes that she, too, fears him, he slips from joyful hope to despair with a look, and moves over to pull the now traditional blow-up- the-lab switch.

But Elsa and Karloff are the perfect couple, too vivid, too alive to have died in the final explosion. Even as Henry and Elizabeth fade from the imagination, the monster and his mate live on forever, icons of the perverse, in our dreams.

This essay originally appeared in the collection Cinema Macabre, edited by Mark Morris, 2005.

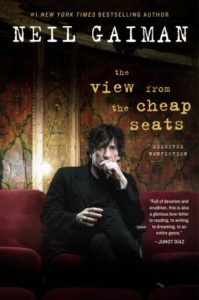

From THE VIEW FROM THE CHEAP SEATS by Neil Gaiman. Copyright © 2016 by Neil Gaiman. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Listen: Neil Gaiman talks to Paul Holdengräber about life, death, and the work of Dennis Potter.

Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman is the New York Times bestselling author of the novels Neverwhere, Stardust, American Gods, Coraline, Anansi Boys, The Graveyard Book, Good Omens (with Terry Pratchett), The Ocean at the End of the Lane, and The Truth Is a Cave in the Black Mountains; the Sandman series of graphic novels; and the story collections Smoke and Mirrors, Fragile Things, and Trigger Warning. He is the winner of numerous literary honors, including the Hugo, Bram Stoker, and World Fantasy awards, and the Newbery and Carnegie Medals. Originally from England, he now lives in the United States. He is Professor in the Arts at Bard College.