Navigating Preteendom in the Shadow of the American Girl Doll

Hannah Matthews Considers the Biases and Blind Spots Behind the Brand’s Most Iconic Products

On September 1, 1998, my girlhood abruptly changed its shape. Two things happened on that blustery back-to-school morning that fell exactly a month after my eleventh birthday. I got my first period; and a colorfully illustrated paperback hit bookshelves across the nation. The book—published on this fateful day by American Girl, the company that had long furnished me with the beloved plastic dolls and accompanying literature that taught me simplistic and sanitized stories about our nation’s history—was called The Care and Keeping of You.

A glossy-covered oversized paperback, TCAKOY was nothing like the four or five American Girl books I already owned, slim chapter books of historical fiction, each series starring a spunky heroine from a specific era and geographical region of my country. Those miniature epics followed a neat and tidy formula, in which our chosen Girl would rescue either her family or a less-fortunate member of her community from (depending on the girl): bullying, racism, poverty, war, various forms of sadness or disappointment caused by America’s ills (but with the help of America’s charms and strengths, of course, which the reader understands to be innate and foundational to our heroine’s personality).

No, this book was an entry into American Girl’s self-help collection: nonfiction, contemporary, and purely educational. Over time, from edition to edition, the aesthetic of its illustrations changed. On the cover you’ll see on shelves now, in the year 2023, three elementary-aged girls of varying heights and skin colors stand together, smiling, in bath towels. One cheerfully holds a toothbrush, her hair wrapped in a matching second towel (for me, a universal symbol of maturity and womanhood.

How sophisticated I felt, the first time I figured out that turban-towel technique!). Another is, presumably, just as naked as the other two under her towel, but has still accessorized it with matching hair clips and sandals. And the one in the middle, pale skin like mine and long hair falling loose around her shoulders, is in a wonder-woman stance, barefoot, beaming proudly, hands planted on her towel-clad hips. These girls seem to know, even as they casually enjoy their sleepover party, or their post-swim-practice locker-room hangout, that they’re headed for the New York Times Bestsellers’ List (five million copies sold, at time of writing). Their lashed eyes are inviting and conspiratorial. They have secrets to share with you: about breast development, pimples, hormones, and periods.

The book is called The Care and Keeping of You. (Its subtitle, then: The Body Book for Girls. In later editions, beginning in 2013, it has been divided into two volumes, The Body Book for Younger Girls and—seductively, attractively, for those eight- to ten-year-olds who yearn for teenagerdom—The Body Book for Older Girls).

The doll was a projection of all my own girlhood fantasies….She was me, without my flaws and scars. She was me, without my fears.

I’ve never been particularly skilled at caring for—and, I suppose, keeping—myself. My relationship with that self (Should one say this self? Here, I am already putting distance between me and her) has ebbed and flowed dramatically for the thirty-six years I’ve inhabited it. I have not always trusted, nor particularly liked, my body and mind, and I have often questioned the integrity and intelligence of my heart. An inability (or maybe an unwillingness) to extend grace or generosity to my own face, my organs, my skin, my scarred, freckled, and cellulite-mottled limbs—and to the inner thoughts and impulses that steer them through the world—has been a ribbon that runs through every part of my life. It has driven me to self-denial, self-injury, self-destruction. It has informed my aesthetic and dietary choices, my dating habits, my parenting struggles, my creative pursuits. The care and keeping of others—my partners, my friends, my pets, eventually my children? Not always easy, maybe, or straightforward, but firmly within my wheelhouse. But the care and keeping of me?

And in 1998, on TCAKOY’s publication day, when I pulled down my underwear and saw that vivid scarlet bloom, expanding and deepening as if it had a mind of its own, as if it would never stop (I briefly wondered if blood would fill our small downstairs bathroom, our house, the town), that battle to keep and care for myself really kicked off in earnest. I had been taught, in bits and pieces and conversations with a handful of trusted adults—most of whom fumbled—about menstruation, a word I loathe as much as the bodily process it describes. I had been told that this moment was special, sacred, a rite of passage into womanhood. I just wanted it to go away, so I could watch The Disney Channel or play with my American Girl doll in peace.

The first edition of TCAKOY came into my life shortly thereafter, and quickly became a bible of sorts. Its author, a writer for the American Girl magazine named Valorie Lee Schaeffer, has spoken of the “cool aunt” voice in which she was determined to speak to the girls experiencing early puberty or prepuberty anxiety and confusion. This aunt, Schaeffer has said, was one of your parents’ younger sisters. A voice imbued with authority and wisdom but not, importantly, that of a parent (or other such form of uncool old grown-up).

Schaeffer correctly identified a need, in this pre-texting, presocial-media landscape, dotted by predecessors like Our Bodies, Ourselves and dryly academic sexual health tomes in which an eightor nine-year-old girl was unlikely to see herself (if she even felt bold enough to attempt those dense and annotated texts collecting dust on her mother or grandmother’s shelf). Schaeffer gave birth to her own first daughter, in the months before TCAKOY was published and hundreds of thousands of girls like me found solace and empowerment in it as we got our first periods, noticed our bodies changing, rode the waves of hormonal mood swings and social-emotional storms endemic of elementary and middle school, and all the dangers and doubts of simply existing in feminized bodies in this world.

Having no cool aunt of my own and no elder sisters, just teenage babysitters and camp counselors (each with their own unique but tenuous grasp on anatomy and reproductive science), the book felt warm, inviting, and—perhaps most important to my terrified, bleeding, self—safe. It didn’t, like the issues of Seventeen magazine I pored over or the MTV music videos I watched in secret when my parents were asleep or occupied in other rooms, leave me with more questions than answers, or an aching (and correct) sense that I would never have access to the belly-chain-adorned flat stomachs and low-rise jeans that would confer the status of (legitimate, worthy, desirable) womanhood. The Care and Keeping of You did not (further) frighten or confuse me.

The Table of Contents is divided along the parts of a young body, with sections titled Heads Up! (including chapters on acne, hair care, braces, and skincare), Reach! (encompassing our underarm hygiene and three separate breast-and-bra-related chapters), Big Changes (all pubic-area topics, like periods), and On the Go (legs, feet, the ominous “fitness,” and issues related to sports and sleep). But the section my thirty-six-year-old-self flips to immediately, including the chapters “Shapes & Sizes,” “Food,” “Nutrition,” and a reprise called “Body Talk: Food,” is called, mysteriously, Belly Zone. Because of my decades-long relationship with marijuana, and cold white wine, and possibly some other unnamed illicit substances along the way (not to mention my age, inconsistent sleep and exercise, scrolling on my phone for hours on end in lieu of brain-sharpening crosswords or sudoku puzzles), my childhood memories often feel like riddles, or escape rooms.

Can I use context clues to figure out if this memory is taking place in Nantes, France, or in Trenton, New Jersey? Can I envision myself as I was, in my lime green jelly sandals and my sparkly butterfly tankini, which shed glitter into the chlorinated depths of backyard pools long forgotten, long confused with one another? Whose house was that, anyway? Reading The Care and Keeping of You now, especially in its updated form, feels like an extended bout of deja vu, sprinkled with worry that I might have amnesia. Hadn’t there been a step-by-step tampon insertion diagram here, on this page? (There had been, and it was removed from the version meant for younger girls due to concerns from parents that it was “too graphic.”) Why isn’t sex or pregnancy mentioned at all (aside from a reference to one’s period being “practice building a nest”) when we know from recent high-profile abortion law cases that nine- and ten-year-olds are becoming pregnant with some horrifying regularity, and struggling to access accurate and affirming information and health care along the way? Why is gender a binary? Why is it assumed so boldly that every one of TCAKOY’s millions of readers will identify as a girl, or have crushes on boys?

Quoted in a 2018 feature in The Atlantic, written to celebrate TCAKOY’s twentieth anniversary, Dr. Cara Natterson (who served as Schaeffer’s medical consultant on the book for younger girls, and the author of its sequel) says that while she’d love to publish a book about sex under American Girl’s brand name, she feels that there’s a place and a time, and that younger girls may need more “safety” from sexual-health-related information as they grow into teenagers. “Tell everyone I would love to write that book with American Girl, but that’s not what these books were meant to do,” she says, in her interview with The Atlantic. “It’s funny how this one book is sort of a safe reminder of what it was like to go through puberty. There’s something really comfortable about that.”

I can’t help but wonder, as an adult who remembers those first creeping buds of sexuality and objectification, vines unfurling in and around my nine-, ten-, eleven-year-old body, which was commented on and joked about in a sexual way, before I ever reached the age of Dr. Natterson’s target American Girl readership: Whom does this omission keep safe? I know it would have been safer for me to learn about sex from a “cool aunt”—accurate and affirming—than from the boys on the back of the school bus and the jokes on morning radio shows. I know the very young patients who travel thousands of miles to the abortion clinic where I work could have used a basic primer, and instead have often received only misinformation (or worse, silence) about the things that have been done to and are happening within their bodies.

I want to ask Dr. Natterson: “Safe” for whom? But I know that cool aunts can carry their own baggage, their own fears, their own anxiety about the perceptions of the world, of the media, of conservative parents of young readers. Cool aunts can be scared to discuss sex, or feel uncomfortable about sexuality and gender identity, too. In 2023, a thirty-six-year-old version of myself opens the book again.

My life now reads like a list of my eleven-year-old self’s wildest dreams, scrawled in gel pen across the pages of a Lisa Frank padlocked diary: has published a book, has an incredibly kind and funny husband who looks like a movie star, has glamorous and beautiful friends, has an important-feeling career, is a mom. And yet I am inhabiting a body from her darkest nightmares, weighing more than I know, or care to know. Tattoos. Adult acne. Bisexuality, and casual sex, and outfits she would consider slutty or frumpy or both. This is actually the body of our dreams, I tell her now, because it is the body in which all of our dreams have come true. My eleven-year-old self rolls her eyes, glares at my thirty-six-year-old body, and silently calls me fat.

That year—the year of TCAKOY, the year of my first period—was the year I first noticed the fractures forming, my mother traveling out of state for work and eventually accepting a new position at a prestigious university in another part of the country, and my father staying home to work at our local college and shepherd me through the wilderness of middle school. After that day, when I was given the book which promised to answer all of my bloody questions—my long-suffering American Girl doll went into the closet. I packed her, and all of her accessories, away that month, a few weeks after my eleventh birthday, removing every trace of her—the bedazzled jean jacket; the plastic, flat-footed Mary Janes (the antithesis, perhaps, of Barbie’s terrifyingly spike-heeled pumps); the fluffy white dog on his little leash—from any common or shared spaces of our drafty four-story house. The house I now shared with only my father; my elder brother also having moved out to attend college that summer in my memory of this time.

But wait. Had he? My brother didn’t leave for college until I was thirteen or fourteen. So, his absence from the house of my memory is not real; it is a figment of my eleven-year-old self’s loneliness, and my thirty-six-year-old self’s warped and nebulous timeline, her perception of the empty rooms through which she wandered, bleeding, before she got up the nerve to tell her dad she needed a pad, and could he please go to the drugstore? But the absence of the doll, I know, was real. Her conspicuous absence in the corner of my poster-covered bedroom was commented on immediately, first by my mother and then by a friend one grade below me, who came over to “hang out” (I had stopped saying “play”) and wasn’t yet ready for nail polish and boy talk to be the sole activities on offer.

Exasperated, I finally brought out the doll. I conceded that we could seat her on the bed with us, and include her in our manicure party. I burned with shame, panicked at the thought of this friend telling other girls about what we had done that afternoon at my house. Terrified of anyone finding out that a real-life American Girl With a Period—just like the ones in my new book, smiling as they grew breasts, smiling as they inserted tampons, smiling as they played soccer and rode bikes (“Try to move your body enough so that you are huffing and puffing or sweating for at least 60 minutes every day,” TCAKOY 2 directs its readers in the latest edition)—still played with dolls.

My American Girl doll was not one of the company’s historical characters, but instead a contemporary, “look-like-you” doll. Because of their exorbitant cost, I was told by my parents, after years of begging, I could choose ONE (1) doll. And choosing between the most coveted historical Girls—my favorites were Kirsten with her platinum blonde braids and confusing Swedish American lore; Samantha, whom I thought of as “the rich one,” with her silky chestnut curls and silver tea set; Felicity, whose cultural context now horrifies me, but who had big hoop-skirted dresses and glamorous green eyes—was simply impossible. If I could only have one, she’d have to be a doll who resembled the popular girls at my school—and thus represented the Ideal Version of Myself that I was sure to become at any moment, if I just bought the right jeans, or was invited to the right pool party. I never named her, because she was not a character in my mind.

With her (relative-to-Barbie, and to the girls I saw depicted in movies and magazines) thick, chubby arms and legs, her rounded, blank-but-pleasant face, and her lack of provided backstory or prescriptive character traits, the doll was a projection of all my own girlhood fantasies. Her parents’ marriage was not slowly unraveling. She was not told by a boy at her school that she looked like a dinosaur, or accused on the playground of “giving a hand job” to a different boy, before she knew what that phrase meant. She did not bleed into her khaki cargo shorts, caught unprepared and unawares, and with only her dad in the house—nor did anything else gross or embarrassing ever happen to her. She was me, without my flaws and scars. She was me, without my fears. She was me, without my period. And so, she had to go back in the closet, for good.

*

In September 1998, my knowledge of global politics did yet not extend too far past the impassioned sparkly gel-pen letter I’d written to Bill Clinton that summer, urging him to “help the war-ravaged people of Kosovo” after hearing that phrase on our car radio (always set to NPR) and becoming distraught. When my bimonthly issues of American Girl magazine would arrive, glossy and colorful, preteen models beaming up at me from covers full of bright fonts promising me tips for “A Hilarious Halloween Bash” and “How to Solve Your Friendship Problems,” I had no thoughts other than: I Must Devour Every Page Immediately. You know that Margaret Atwood poem, the one that goes, my logic about you is a starved dog’s logic about bones? That was exactly the nature of my primal hunger for all things AG, tearing through jokes from “The Giggle Gang” and binder-decorating tips in the “School Stuff” section of the magazine.

Especially now that I was “too old” for the doll, I needed a new portal through which to escape into a world where—even when there were bullies, or pimples, or sick pets, or even fighting parents (I don’t recall the magazine tackling divorce, though I’m sure it must have at some point, since much of its readership would have already been intimately acquainted with the concept)—my hair could be straight and shiny, my back-to-school outfit perfectly polished, and my tankini-filled, pineapple-themed summer pool party a smashing success (never mind my own distinct lack of pool, rivaled only by my lack of tankini-clad Cool Girls to swim in it).

“I think I look fat,” writes a reader, in the “Body Talk” subsection of TCAKOY’s Belly Zone. “I know I’m not, but I just can’t help feeling this way and hating the way I look. I’m miserable I exercise, but I still feel too big. What should I do?”

“If you need to lose some weight,” the book answers, “that’s one thing. But if your brain is just seeing your body in a way that’s not true, you might need help changing that.” And then: “Try not to obsess over the mirror until you and your parent figure this out.” Which parent, I wonder, would be figuring this out with me? My mother, who had recently become enamored of the Atkins Diet? Or my father, who would warn me about “empty calories” in sports drinks, and speak often with disgust about how our state was named “the fattest in the nation” thanks to all the fast-food drive-throughs. My father who, one night when I was fourteen, out of frustration with my refusal to join him and my mother on a family walk, said to me five words that will remain tattooed on my brain for the rest of my life: “This is why you’re overweight!” I wasn’t, as it happens, overweight when he said this. I had just recently been informed by my pediatrician that I was in fact not on the wrong side of that imaginary, arbitrary red line—whatever number on the scale marked its location—but needed to be mindful, as my weight was “toward the high end of normal.” More words I hadn’t asked for, more words that I can recite from memory now, as someone who could not tell you the capital of Montana or identify the correct application of Pythagorean Theorem.

*

“Taking care of your body is a lifelong job,” reads the Twentieth Anniversary Edition of TCAKOY. “Puberty is a special time of growth and change. Everybody goes through it. It begins for most girls between the ages of 8 and 13,” narrates Emily Woo Zeller in the audiobook script of the book, “and it ends when your body has reached its adult height and size”—here, thirty-six-year-old me bursts into rueful and angry laughter—“around ages 15 to 17.”

But even as my cool aunts forget, or shy away from—or maybe even intentionally ignore, as we all are want to do along the path of unlearning our biases and blind spots.

To teach eleven-year-old girls, in no uncertain terms, that our high school bodies are our adult bodies may promote a certain “keeping” of ourselves, alright—a vigilance, a border and the implied violence of its maintenance, a tight control by any methods those oft-mentioned “trusted adults” may prescribe—but confidence, self-celebration, care? My thirty-year-old body, an ocean of cellulite and stretch marks and therapy undertaken to unlearn those very same methods of “keeping” between it and its seventeen-year-old iteration, shakes its head.

*

In Body Work, a shimmering and sharp examination of her own memory and perception, Melissa Febos writes: “Each person who was present for the events of which I have written has a different true story of them.” Valorie Lee Schaeffer and Dr. Cara Natterson, I’m sure, have their own true stories to tell, about what has been helpful and harmful to their young-girl selves, and to the young girls in their own lives. I know they did not envision the garden that would grow in my psyche, for example, from the seeds they planted with their words about fitness and diet and body size. Cool aunts can have internalized misogyny and disordered eating patterns. Cool aunts can be fatphobic, too.

And what am I forgetting, if the granular details of these sentences, written twenty or ten or five years ago by these cool aunts of mine—each syllable and sound—do take up so much of the increasingly limited parking space in the run-down garage that is my memory in adulthood? What am I misremembering, or not seeing clearly, if the calories in one hard-boiled egg are such permanent fixtures, blocking the light from other angles? Maybe I forget the look on my father’s face when he apologized, and said that’s not what he meant, and all of the ice cream cones he has shared with me, the elaborate meals he has cooked for me and encouraged me to enjoy. Maybe I mischaracterize my mother, who wrestled the very same 1990s and 2000s demons that almost killed me (Weight Watchers, SELF magazine, diet yogurt commercials), and so many other demons before those. A woman subjected to nearly four decades more of “friendly” or “healthy” diet and fitness advice than I have been, and who told—and tells—me about how beautiful she finds me, how strong and athletic, how acceptable and worthy and good in all my forms.

In the sequel for readers further along on their puberty journeys, TCAKOY: The Body Book for Older Girls, food, nutrition, exercise, and weight are a major focus from the very first page. Dr. Natterson, the author of the second volume, is particularly concerned with setting strict and explicit limits around our dietary choices for us. For example: “Even though ice cream is a dairy product, it has so much sugar that it really isn’t a healthy source of calcium or protein—it counts as a treat instead.” And foods that count as “treats,” we learn on the next page, are to be avoided and feared.

“Respecting your body is as much about keeping bad things out of it as it is about putting good things in,” Dr. Natterson scolds us, in a sentence that makes perfect sense to my eleven-year-old self, and makes my recovering-orthorexic-and-anorexic-adult-self clutch at my throat and my heart. Keeping bad things out of my body. Bad things. Bad things.

The bad things I should try to keep out of my body, I want to scream now—at Dr. Natterson, at the magazine editors, at all of our parents, at my eleven-year-old self, at my current self and at any children who have been or may ever be born from this body–might include: cigarettes, excessive alcohol or caffeine, sexual partners who don’t respect me or like me, partners who don’t treat said body with care and tenderness and the reverence it deserves.

That category does not include: ice cream.

But even as my cool aunts forget, or shy away from—or maybe even intentionally ignore, as we all are want to do along the path of unlearning our biases and blind spots—the subjects and concepts that other books for kids have since tackled gracefully and accurately, I don’t fault them entirely. American Girl is, in some ways, an inherently conservative and cautious brand. Careful about its history lessons, careful about its depictions of our girlhoods (and of the bodies those girlhoods inhabit, and what we should do with them). That even now, there are no fat American Girls; that the scholar Dr. Sami Schalk has written at length about the brand’s occlusion of disability and disabled American Girls themselves; that the aforementioned tampon diagram was enough to be considered “controversial” and “too graphic” by a loud minority of parents who bought the book; these should tell us plenty about the America in which we were Girls.

__________________________________

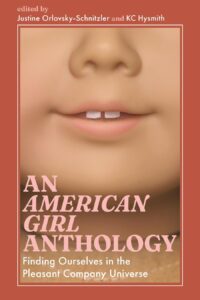

From An American Girl: Anthology Finding Ourselves in the Pleasant Company Universe, edited by Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler and KC Hysmith. Copyright © 2025. Available from University Press of Mississippi.

Hannah Matthews

Hannah Matthews (she/her) is a writer, poet, musician, community health care worker and public library worker. Her debut book, You or Someone You Love (Atria, 2023) was a Kirkus starred title and a finalist for the New England Book Award. Her second book, Sweet-Blooded, is forthcoming from Beacon Press. You can find her writing in Vogue, TIME, McSweeney’s, Esquire, The Guardian, Elle, Electric Literature, Jezebel, LitHub, and other outlets. She lives in Maine with her family.