I won’t tell you what my mother was doing in the photograph—or rather, what was being done to her—just that when I saw it for the first time, in the museum crowded with tourists, she’d been dead five years. It broke an explicit promise, the only one we keep with the deceased, which is that there will be no more contact, no new information. In fact, my mother, who was generally kind and reliable in the time she was living, had already broken this promise. Her two email accounts were frequently in touch. The comfort I took in seeing her name appear, anew in bold, almost outweighed the embarrassment of the messages that followed. She wanted me to know that a small penis size was not an indictment against my future happiness. She hoped I would reconsider a restaurant I might have believed to be out of my budget, given a deal it made her pleased to share. She needed some money for an emergency that had unfolded, totally beyond her control, somewhere at an airport in Nigeria. Though these transmissions alarmed me, it was nice to be able to say what I did, when an acquaintance or administrator at the college where I teach saw my eyes on my phone and asked, Something important? It was nice to be able to say, Oh, it’s just an email from my mother. Given how frequently we had written while she lived—the minute logistics of a renovation, my cheerful taxonomies of backyard weeds—she avoided the spam filter after her death, and I could not bring myself to flag her.

She had not died as she lived. Does anyone? Though my mother had not been vain in a daily sense, she often made me, in the weeks of her dying, rub foundation onto the jaundice of her skin. This was something she could have done alone—she never lost power in her hands, as far as I knew—but one of the dying’s imperatives is to make the living see them. This is nobody’s fault, but it is everybody’s burden. That sounds like something my father would say, half-eating, in the general direction of the television: Nobody’s fault, everybody’s burden. Perhaps he did, and this thinking made its way into mine. I don’t always know well where I’ve left a window open.

The photo was part of a multi-artist retrospective, curated less to discuss a school or approach than to cater to nostalgia for a certain era in New York. Shows like these are a dime a dozen here, and they are not of the sort I seek out, having lost most interest I might have had in the type of lives and rooms they always feature. Bare mattresses on the floor, curtains that are not curtains, enormous telephones off the hook, the bodies always thin but never healthy. Eyes shadowed in lilac, men in nylon nighties pour liquor from brown paper bags into their mouths. A woman with a black eye laughs, her splayed thigh printed with menstrual blood. These photographs are in color, the light strictly natural. There is always some museumgoer finding her imprimatur there, looking affirmed and clarified about the ragged way she’d arrived feeling.

That day I had come to the museum for a show of paintings, landscapes of Maine refashioned with a particular pink glow the painter must have felt when he saw what inspired them. I was wearing a shirt that buttoned high on my neck, and my rose-gold watch, vintage, which I had just repaired. The wedding ring remained. It wasn’t that I had any hopes for reconciliation, but its persistence on my finger was a way of matching inside to out. I needed to be reminded, when I caught myself deep in a years-old argument with my husband, alone and furious on the mostly empty midday subway, that he had been real—that my unhappiness was not only some chemical dysfunction of mine.

I decided to take the stairs, and then to pass through the exhibit in question: I had an hour to spare, and I thought it might be an interesting metric. How little I related could be the proof of a transformation I had undergone, a maturation evident in how I saw and felt. When my husband met me, twenty-two to his forty, he saw a girl with a rough kind of potential, and he tended to me as one might a garden, offering certain benefits and taking others away. He did not wish me to grow in just any direction. That I allowed him this speaks just as poorly of me. I was once a girl with an exquisite collection of impractical dresses—ruched chiffon, Mondrian prints—and a social smoking habit, a violent way with doors and windows. I left him in taupes, my arches well supported, my thinking framed in apology. It is clear there were parts of me that must have been difficult to live with, namely an obsessive thought pattern concerning various ways I might bring about my own death, but also clear that I rose to the occasion of this malady with rosy dedication, running miles every day and recording the impact of this on my mind, conceiving of elaborate meals, the hedonistic pleasures of which I believed spoke to my commitment to life. Could a person who roasted three different kinds of apples for an autumn soup really be capable of suicide? I asked him this question laughing, wooden spoon aloft, during an argument about a drug I did not want to take. Doesn’t the one cancel out the other, leaving you with a basically normal wife? They could delight me, my obsidian jokes, but he saw them hanging from me like statement jewelry, heavy, aggressive, things that could not be forgotten even as I spoke, quietly and practically, about the empirical world. He began not to trust me on issues I saw as unrelated: what a neighbor had said about a vine that grew up our shared fence, a letter from the electric company that I claimed to have left on his desk.

I passed through the contiguous rooms, high-ceilinged and white, as briskly as could be called civilized. Whatever my feelings about the work, I never want to be one of those people rushing through a museum, intent on immunity—I was here, their bodies say, and that was it. It is true I sometimes court discomfort, that I will deny my headache an antidote, and that I don’t expect to feel the same way from one hour to the next. This was a quality my husband feared, then hated. That’s the usual trajectory, it might be said. If we don’t talk to the thing we are afraid of, it becomes the thing we hope to kill.

All the people in the room were young women, and I felt tenderly toward them, their damaged wool and winged eyeliner and overstuffed shoulder bags. They interested me more than the photos. What could I tell them, from just the other side of thirty, except that things did not seem to exist on the continuum we needed them to—so little of life was a rejoinder to something said or done earlier, the opportunity to, as school had often demanded, show what you had learned. Your real self was mostly revealed in negotiation with the unforeseen element. How did you behave when the emergency room bill arrived, triple the estimate? When someone you loved was suffering, how long did it take for you to wonder about a life that didn’t include her? I had sidled up to one of them, the girls, whose face intrigued me particularly, a saturation of peachy freckles she had made no attempt to cover up. Hanging there, the object over which she was pouring her young mind, was my mother.

As far as I knew, my mother had lived in New York City for only six unfortunate months. The image I associate with them is not a photo of her looking bewildered by the Rockefeller tree or exposed on the steps of the Met—they don’t exist—but rather a gesture she would make, at her suburban dining table, if ever asked to describe her time there: a low hook of the hand, swiped an inch or two to the left. Total dismissal. Sometimes, on the rare occasions she’d had more than her characteristic half-a-glass with dinner, a blush and a remark. I had no idea what I was doing there, she would say, and pat the hand of my father, the ostensible representative of a life she found a year later and understood quite a bit better.

About the photo in the museum, I will tell you this: my mother looks like someone who knows exactly what she is doing.

Seeing her like that, I started to cough and I could not stop. There is very little ambiguity about what has gone on in the pictured bedroom that contains her, shot from just outside it so that the leftmost third is a slice of peeling door, paint riddled with thumbtacks. There is the characteristic mattress, right on the floor, the open window and fire escape. There is some rubber tubing, knotted in places, elevated above the usual detritus on a milk crate. The inner sleeves of records, the cellophane casings of cigarette packs, a battered silk tie one must assume, from its crippled shape, has been used otherwise. That time passed for me, there in front of the photo, was a separate cruelty, for it came with no palliative or normalizing effect, and so the third minute I took it in elided with the ninth and the twelfth. A German tourist, the kind of spokesperson for a concerned and patient group of them, touched a finger to the back of my elbow. It was obvious, from the damp focus of their faces on mine, that it was not the first time he had spoken the word in my direction. “Please,” he said. “Please,” I replied, stepping back so that they could see her.

Though all identifiable marks were in place, the mole I had liked to press at the base of her jaw, the gap in her eyebrow from a childhood accident with the Girl Scouts, there was nothing about my mother’s facial expression I recognized. It had not come up in her rare flirtations with anger, episodes about which she felt embarrassment for days. A faulty appliance without a warranty, a time I had, at fifteen, responded rudely to an elderly neighbor’s offer of homemade rice pudding—Ev, whose teeth looked to me like towns devastated by hurricanes. Young lady, my mother had said, that the cruelest thing she could think to call me, your days aren’t any bigger than hers. Even before she was ill my mother was a diminishing creature, eliminating distinctive or inconvenient parts of herself by the year. At fifty she stopped wearing the perfume she had for decades, her one luxury, thinking an insistence on a certain scent was an affectation of the young. What do people need to smell me for? she said, with a horsey puff of air out the side of her mouth. Once, from the passenger seat during a trip home, I watched her wait patiently while the man driving the car in front of us, by all observations asleep at the otherwise empty intersection, leaned farther across the wheel. Honk, I said, but my mother would not honk. Honey, have you considered he might need the sleep? Choose a radio station, for god’s sake. There are some good ones around here, you know.

The Germans had formed a barrier around my mother, talking and gesturing, so I exited the museum, taking the stairs as my husband had always insisted. A little bit of exercise was a phrase he kept spring-loaded. The gap in our ages was hardly noticeable to others, and I had often imagined the point when the stunning preservation of his youth would overtake the rapid deterioration of mine. Growing up his beliefs as their rigidity dictated, I was something like an espalier, the distance between the vine and the thing that trained it almost imperceptible. I wanted to call him, to wash his reasonable pragmatism all over the issue of the illicit photo, but our terms would not allow it. I can’t deal with another crisis, my husband would say, the last year we were together, in response to vexes I saw as relatively small, a mix-up at the pharmacy over the drug I agreed to take, some passive-aggressive email from a student I read out loud in the kitchen, hoping to parse. I can tell you’re in a state, he would say, hands raised like an outdated television preacher. Rather than responding to my speaking, he took to waving at it, scenery to be considered later with the right amount of rest and reflection.

I can’t imagine the man, he said more than once, who would have an easy time living with you. This hurt particularly, for he had a fabulous imagination—a jaunty talent with a colored pencil, a habit of coming up with a song on the spot, a fond feeling for the absurdity of animals. I began keeping a tally of my behavior, days I had been so anxious at the incursion of these thoughts that I wept or went sleepless, others when my charm had been big and flexible. On a New Year’s we hosted, I built fantastical hats of construction paper and balloons, things that looked like cities of the future. On his forty-fifth birthday, in the park near our house, I hid his ten favorite people behind his ten favorite trees, and guided him on the snowy walk to discover them. I always scanned his face, on occasions like these, for a look of recognition, one that would say, Here, here you are.

Contact between us now consisted mainly of three words, even the contraction never parted into its constituents. Hope you’re well, he wrote. Hope you’re well, I wrote. Hope you’re well! Hope you’re well! The statement never altered into a question, and with time it began to read to me as a kind of threat, beveled, ingenious. To his last Hope you’re well, six weeks before, I had not replied, and I believed that was the end he had in mind. Pills in a blender with strawberry ice cream, I thought. An email scheduled a day ahead of time with very clear instructions. We had been separated a year.

__________________________________

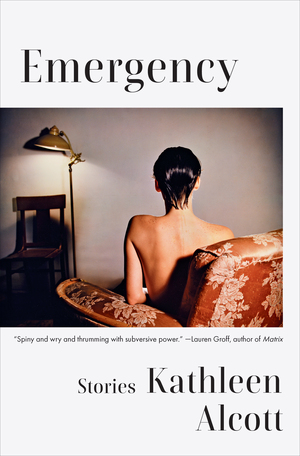

Excerpted from”Natural Light” from Emergency: Stories by Kathleen Alcott. Copyright © 2023 by Kathleen Alcott. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

__________________________________

Kathleen Alcott will discuss her new short story collection, Emergency, with Laura van den Berg at P&T Knitwear on July 27. RSVP here.