Namwali Serpell on the Complex Processes That Create Fiction

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of The Furrows: An Elegy

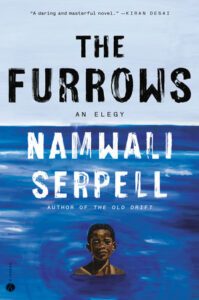

Namwali Serpell is one of the most inventive, evocative, erudite writers at work today. In The Old Drift, her multi-award-winning first novel, a three-family saga that spans some nearly two centuries in Zambian history and features a chorus of mosquitos, she mixes styles from Gothic to Afrofuturist. In her dazzling new novel, The Furrows: An Elegy, she is real, surreal, noirish, and more.

Hovering over her work is the question of what draws her to be so experimental in form: “If Toni Morrison’s words are true, then it’s because writing is reading, and I am drawn as a reader to a wide variety of genres and to the authors who have experimented with them,” she notes. “But to be honest, I think my work is only modestly experimental if you consider, say, postmodernists like Morrison or modernists like Joyce, or Moby Dick, or 18th-century novelists like Sterne or Defoe, or the book that’s often considered to be the very first novel, Don Quixote, which definitely mixes styles!

Experiment is endemic to literature. I’m happy to be entertained by more ‘conventional’ texts, I suppose, but even when we consider those: Jane Eyre is working with at least three genres; Dickens alternates third and first person in Bleak House; Austen wrote a satire of the Gothic in Northanger Abbey….I’d wager that the desire for ease of consumption has warped our sense of what is truly experimental.”

Like her books, a conversation with Serpell is immersive, even by email, creating an electrical connection between two points (she was in Harlem, I was in the Northern California, where she used to live).

*

Jane Ciabattari: I believe the last time I saw you IRL was at the 2019 Bay Area Book Festival in Berkeley, when I moderated a panel with you and other first-time fiction authors Jamel Brinkley, and R.O. Kwon How have you managed during these Corona years of turmoil and uncertainty? How many moves have you made, for fellowship, for teaching? Where are you living now?

Namwali Serpell: Yes! That was such a fun panel—I have vivid memories of laughing a lot as we talked about endless revisions! Corona has been difficult, of course, but not nearly as difficult as it has for others. Everyone in my family survived the pandemic; no one has had lingering effects (knock on wood); and my partner and I have somehow been spared catching it even once (drumbeat on wood). I feel that, in many ways, Dr. Rona (as I took to calling her) has forced many people to change their perspective on life and the world, myself included. It’s like this giant roving lens. It seems to magnify and clarify and sometimes scorch all that falls under its utterly impassive gaze. I spent much of the pandemic at home alone, first in my San Francisco apartment, then in my Harlem apartment.

I have about five books in my head at any one time.This is not so unusual for me—to move around between hard-won rooms of my own. But over the course of the months between spring 2020 and spring 2023, I went from teaching at Berkeley (or really at Zoom U) to two fellowships at the NYPL for a year to teaching at Harvard (or really at U Masked), commuting from New York a couple of days a week. I moved across the country; I became a full professor; I changed university jobs; I bought a condo in Harlem, which I just moved into; I published my nonfiction book, Stranger Faces; I finished this novel, which is now coming out—oh, and I just got engaged. All of these massive life transitions were, oddly enough, set in motion before the pandemic, but they have been marked, for better and for worse, by that other seemingly universal feature of the Rona years: the near-hallucinatory suspension of time.

JC: On that BABF panel, you mentioned that you started The Old Drift in 2000, while you were getting your Ph.D. When did you begin The Furrows? Were you also working on critical essays? How do you accomplish your intellectual multitasking?

NS: I actually began The Old Drift while I was in college (I graduated in 2001), and worked on it off and on through graduate school (I got my PhD in 2008). I started The Furrows in that last semester of graduate school and worked on it off and on through my tenure track process at Berkeley (I got tenure in 2014); it was a twin book to Seven Modes of Uncertainty, the scholarly book that got me tenure. I put the full draft of The Furrows in the proverbial drawer in 2015 and turned back to The Old Drift. This was partly because I needed more time away from The Furrows to see it anew and partly because a piece excerpted from The Old Drift, “The Sack,” won a prize [the 2015 Caine Prize for African Literature] and that precipitated the sale of the novel as an incomplete manuscript (I eventually excised that piece from the novel). I wouldn’t call what I do multitasking—that sounds too efficient! I just don’t write in order.

When a real idea comes, I know it. And so I have about five books in my head at any one time—as they arrive, I put notions and figures and scenes for each into various scattered notes apps. I work on each project for an extended period less when I can than when I have to—the “having to” having to do with internally and externally imposed deadlines but also with a mysterious sense of urgency that grabs me at random. It’s important to me that this process be organic but I also feel I must take advantage of whatever time I have when I’m not teaching (weekends, summers, fellowships, sabbaticals). There are many to-do lists and calendars in my life to facilitate this negotiation, but they are woefully provisional, aspirational, ever-evolving, asymptomatic.

JC: Can you describe the journey of The Furrows? What inspired the book, and its title, which frames it as an elegy? How has the shape of The Furrows shifted over the years of work?

NS: The first scene of the novel, which you describe below, came to me as a dream in the spring of 2008. I was swimming in the sea with a little boy (I now know it must have been my nephew, Chedza) and a storm picked up; I had to swim us back to shore, pushing us through what I call in the novel “the great grooves in the water, the furrows.” The grip of panic I felt when I woke up, combined with a deep sense of love, reminded me of how I used to feel when I woke up from dreams about my late sister, who died when she was 22 and I was 19.

I decided to write about the uncanny, eruptive rhythm of grief. The structure of repetition came to me in 2009. I was in New York for the summer and had the time to turn back to fiction. I had another dream about my sister that helped me conceive the iterative shape of “losses” and “reunions” in the book. The switch to Wayne’s story in the second half came to me one half-asleep, half-awake morning in my apartment in Berkeley that fall. I decided to make Part II noir because I wanted to give the reader something more plotty to hang on to after the unconventional Part I. When I returned to the novel in 2019, I reverted to this structure, which I had veered from in later drafts, daunted by readers’ feedback. And I made three major revisions.

One, I converted the novel from the third person to the first person, which, I should say, involved far more than Find + Replace, given the distinct voices involved. Two, I put Wayne’s doppelganger “Will” in prison, decided he wasn’t a Dominican man with no lines but an African-American man with a lot to say, and mapped his story onto the first doppelgänger tale in English, Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” (I published Will’s sections of the novel as a standalone novella called “Will Williams”). And three, along those lines, I transformed the noir feel to Part II into more of a crime fiction/ horror feel, as I’ve always loved and wanted to engage with those genres, and I wanted something edgier for the book; this entailed cutting a lot (as with “The Sack” and The Old Drift, another published piece, “Take It,” that I’d excerpted from The Furrows ended up being deleted) and making Wayne’s quest less pecuniary and more vengeful.

JC: The opening lines—“I don’t want to tell you what happened. I want to tell you how it felt.”—seem an invitation to the reader, and also a challenge. Twelve-year-old Cassandra witnesses her seven-year-old brother Wayne’s death by drowning, but shortly thereafter his body disappears. The experience of grief is complicated because Cassandra and her parents also are dealing with this harrowing ambiguity—no chance for a ritual of completion, a resolution, and end—as well as the fragmentation of trauma. Each takes a different approach; all are splintered. What were the challenges of portraying these individual reactions?

I don’t really “come up” with things about characters; it’s more like I learn about them as I write.NS: This is a very accurate reading of what I’m trying to convey. I didn’t find it challenging to portray these reactions, though. Let me explain. I don’t really “come up” with things about characters; it’s more like I learn about them as I write. Morrison’s words about this, “writing to me is an advanced and slow form of reading,” really resonate with me. So each member of the family always reacted to Wayne’s loss in the ways they do. Charlotte refused to believe he’d died and started Vigil; Bernard left the family and started a new one elsewhere; Cassandra struggled to mourn in the face of the family’s denial of her experience, “her truth.”

The same is true of Part II—Wayne was always looking for Cassandra’s brother; Mo was always the father who he felt had betrayed him. But what I learned as I wrote and revised was why they each reacted in the ways that they did. So I’d say it was a challenge to learn about these people, to understand them well enough to portray. But I really enjoyed that challenge! I am a very curious person, aka a gossip.

JC: What gave you the impulse to shift the narrators midway through The Furrows, from Cassandra (or C or Cee) in Part I to Wayne (and also Will) in Part II?

NS: I speak to the impulse above, but the reasoning I developed for it after I finished (self-justification always being retrospective!) is three fold. One, I wanted an external view of Cassandra, whose unreliability I was already trying to sharpen by putting her story in the first person. There is a striking moment in the last chapter of The Sound and the Fury where we finally get to see Benjy from the outside, after having had the tortuous experience of being inside his consciousness and the torturous experience of hearing what his brothers think of him. I wanted a little of that effect. Two, I wanted to explore what that little black boy’s life might have been, along two different paths of becoming a black man, and to have a sense of his preciousness as a lost child linger over them, and color how we perceive them. And three, I wanted to explore the schisms within race, between black people—both the way gender and class can divide us up and the way systemic racism structurally pits black people, especially young black men, against each other.

JC: Wayne’s mentor Mo has a hand in training him for life on the streets of San Francisco and Berkeley, offering him sermons from the Koran, lessons in street scams, moral training (“Not Retribution, restitution.”). How important is Mo as a moral compass for Wayne?

NS: Mo is a father figure, so it’s important that he gives a moral code to Wayne at a time when he is untethered from family, from relation. But their argument about that moral code is precisely why they part ways. The novel presents several competing value systems, which I would go so far as to call incommensurable—they cannot be weighed against each other to determine which is “correct.” It’s undecidable whether honesty or loyalty is more valuable, whether forgiveness or justice is more important, whether romance or friendship is the better form of love. It depends, we say. The novel sets these value systems against each other so that they coexist, as they do in life, so that we might argue about them, work through them, wonder about them.

JC: The novel’s finale comes in a daring and imaginative burst. Because I’ve been in the Bay Area during times of great natural turmoil, I find it both surreal and believable. You’ve said you wrote it during a rare Bay Area thunderstorm? Can you describe how that scene evolved?

NS:I confess, I once “discovered” the remarkable and eerie Palace of Fine Arts with two friends. So that was my setting. I knew that this final reunion, like all the others, had to be a catastrophe. So that was my plot. I taught To the Lighthouse in an introductory lecture course at Cal, and rereading the novel I rediscovered a scene that seemed to draw the sublime and the beautiful together in a way that perfectly captured the apocalyptic atmosphere of the Bay Area. So that was my imagery.

And I had stumbled onto the technique of running dialogue together into one big paragraph without attributing sentences to individual speakers early on, while writing the first “reunion” scene in Boston; it didn’t matter who was saying what, I just needed there to be a material exchange of language, mostly cliches, to build a brimming set of feelings between these people; a wonderful discussion of a love scene in Jose Saramago’s Blindness in a graduate seminar I taught inspired this. So that was my language. This is all a retrospective dissection of the evolution—I’m not this methodical in practice! What I do know is that this chapter underwent the fewest changes out of all of them since I first wrote it in 2011.

JC: Your critical work seems to be in conversation with your fiction. In The Furrows, C glimpses Wayne’s face in the face of strangers, lovers, in disconcerting ways not unlike the “proliferation of similar faces in Psycho” you write about in Stranger Faces. Plus Wayne has doppelgangers, and near the end of The Furrows, C ducks into a Hitchcock double feature at the Castro Theatre. There are also echoes of your Seven Modes of Uncertainty (2014) (cue cover of Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity), in which you write of how Nabokov’s Lolita “does not guide or imitate readers’ moral values; it unsettles them.” Unsettling is a good word for The Furrows. How do you moderate that inner conversation among your writerly selves?

Fiction is one of the most complex artifacts that humans create.NS: I like all of these connections, but none of them is intentional! While, as I hint above, teaching often inspires me in either direction, I have never had an idea in my critical work about which I have consciously thought “I shall try to enact this in a story”; nor have I ever pictured a scene or a character and then decided to incorporate it in an essay. I’m glad there is a conversation happening between these genres of my work. But I try to stay out of it!

JC: The Furrows has echoes of W.E.B. Du Bois, Toni Morrison, Virginia Woolf, and Edgar Allan Poe. How have these and other authors inspired you?

NS: See above—to experiment! Fiction is one of the most complex artifacts that humans create. It demands so much of us. It works at so many levels. And those authors who persist in pursuing this vocation, in finding their way through their strange visions in order to convey them to others, in slowly walking the inner circle of their own minds—to feel that sense of commitment is like joining a transhistorical family of a kind. I’ve always liked E.M. Forster’s image of this more than T.S. Eliot’s notion of capital-T “Tradition”: in Aspects of the Novel, Forster says we are to visualize the novelists he considers as “seated together in a room, a circular room, a sort of British Museum reading-room—all writing their novels simultaneously.”

JC: What’s coming next? Are you working on a third novel? More criticism?

NS: Per above, I have something like four novels and a short story collection “in mind,” but the one I feel likeliest to work on next is a novel I’ve drafted about two thirds of; it’s about a black home-care nurse from D.C. named So-So. I’m itching to get back to it—hopefully I can find time in the spring when I’m on sabbatical. As for criticism, I’m interested in putting together a triptych of three “Afrofuturists” avant la lettre. But I’m focusing for the next couple of months on an essay about gender and style in contemporary fiction, and an essay about grief and resurrection in literary theory.

__________________________________

The Furrows: An Elegy by Namwali Serpell is available from Hogarth, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.