Namwali Serpell on Approaching Toni Morrison’s Work As a Reader and a Critic

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of On Morrison

Namwali Serpell is one of the most evocative, erudite, and original writers at work today. She mixes Gothic and Afrofuturist styles in The Old Drift, her first novel, a three-family saga that spans nearly two centuries of Zambian history. (My favorite part is the recurring chorus of mosquitos, which even moves into the future, which is why this first novel won the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Science Fiction, along with Anisfield-Wolf book award and the Los Angeles Times’s Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction.) Her collection of speculative essays, Stranger Faces, a 2020 National Book Critics Circle criticism finalist, showcases her wry wit and wide range of cultural interests, from Derrida to Keanu Reeves. Her dazzling, inventive second novel, The Furrows: An Elegy, an NBCC fiction finalist, shifts from realistic to surreal to noir to horror, with nods to William Empsom, W.E.B. Du Bois, Virginia Woolf, Zora Neale Hurston, Alfred Hitchcock, and Toni Morrison (the title echoes a line from Morrison’s Paradise: “Beware the furrow of his brow”).

It’s no surprise that On Morrison, published on the day before Toni Morrison’s birthday, opens new portals into the work of one of the most revered authors of our time, with deep reading, archival gems, and original analysis of Morrison’s syncretic genius. What was your reaction when upon your first reading of Toni Morrison’s work? I asked Serpell in our email exchange. “I have a distinct memory of a first encounter, not with Morrison’s work as such, but with Sula,” she responded. “I first read her second novel one lazy summer, the kind the novel itself describes:

Then summer came. A summer limp with the weight of blossomed things. Heavy sunflowers weeping over fences; iris curling and browning at the edges far away from their purple hearts; ears of corn letting their auburn hair wind down to their stalks.

“I was in my mid-twenties, attending graduate school, and I was house-sitting for one of my professors. There were not many books I read during that time of my life that I didn’t mark up with a pencil. I had read and reread Beloved and Jazz in college and grad school and written papers about both; I had recently given a talk on Beloved. But Sula was different: I read it on an impulse, a sudden urge to throw away time that I didn’t have to spare. That summer afternoon, when I should have been working on my dissertation, I languidly plucked an old paperback of Sula from my professor’s bookshelf. I admired its vintage cover. I always meant to read this one.

“I remember lying across the white sofa and I remember rays of sunshine lying across the living room, me and the sun rays spinning slowly into new positions as the day passed. I remember the sun falling down right when my tears did, when Nel’s did, at the very end of the book: “The loss pressed down on her chest and came up into her throat. ‘We was girls together,’ she said as though explaining something. ‘O Lord, Sula,’ she cried, ‘girl, girl, girlgirlgirl.’ It was a fine cry—loud and long—but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow.” I will never teach this novel, I decided, or write about it. It would be a kind of betrayal.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did On Morrison evolve?

Namwali Serpell: I changed my mind. Two decades later, I was asked to write an introduction to a new edition of a Morrison novel, and I jumped to call dibs on Sula. I reread the novel during the pandemic, in the bedroom where I spent most of my time that year, grey New York growing green outside my window. This time, I did have a pencil in my hand. I underlined and took notes; I drew diagrams and word maps. I tried to figure out why the novel had moved me so much, and what it had taught me—about reading and writing; about the self and love.

I would say that reading Morrison over the course of my life as a fiction writer has given me the courage of my artistic convictions.

When I next found myself in a classroom, back as a professor at Harvard after twelve years at Berkeley, I decided to teach a course on all of Morrison’s works. Before I gave my closing lecture on Morrison’s second novel, I told my class: “I will not be reading the end of Sula today. If I do, I’ll end up in tears.” I drew triangles on the board; I analyzed psychosexual dynamics; I spoke about the significance of names. And in the end, I read the end and I cried anyway. I confessed this to my then-fiancé, now husband, in my now weekly reports to him on the course—about all I was teaching and all I was learning—and after listening to me, he suggested I turn my lectures into a book. I was reluctant but then I did some archival research and discovered some incredible new things. I taught the course again and I wrote the book.

JC: In your opening section of the book, “On Difficulty,” you note that “the ultimate source of Morrison’s famed difficulty was not, I would submit, her intersectional identity, her prickly personality, or her contrarian politics. It was this very insistence on plumbing the depths of black aesthetics—’very complicated, very sophisticated, and very difficult,’ misunderstood and understudied—in her writing. This is what I set out to explore in On Morrison….” What were the biggest rewards and challenges in meeting your intention?

NS: The rewards are self-evident. There are few fiction writers whose works bear rereading and formal analysis so well. Morrison’s work is wonderfully rich, and her bent toward ambiguity means that there are many interpretations we can draw out of her stories, her sentences, her words—even her punctuation marks. She was constantly growing and changing as an artist, so every novel has a distinctive style and fresh set of philosophical questions to consider. Finally, she spoke eloquently—in interviews and talks and works of criticism—about her own formal techniques and their implications. She teaches you how to read her.

The challenges have to do with my need, as I say, with Miltonic tongue in cheek, “to justify Morrison’s ways to us.” Her formal choices are both modernist—she is less interested in telling a story straight than in using narrative to shape her readers’ experience—and black. These two aesthetic modes both evince the kind of “difficulty” that Morrison prized and that American culture despises. So I have to mount a defense of complexity and ambiguity before I even begin to unpack how she wrote and why. This is especially hard when it comes to black aesthetics: people think they know how Morrison’s work is black, but they don’t always recognize the sophisticated cultural forms and techniques from the diaspora she was playing with and refining.

JC: You mention Morrison’s study of the modernist writers William Faulkner and Virginia Woolf (her 1955 Cornell master’s thesis focused on their work, and she has acknowledged using some of their themes and formal techniques in her own novels: “Woolf with her gaps, Faulker with his delays…”). Yet from her first novel, The Bluest Eye, on, her own experimental approach and deep knowledge of global black culture shines through. How would you distill her originality over the course of her eleven novels?

NS: I would say that it’s syncretic—characterized by an amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought. Morrison both writes about and uses techniques that reveal the necessarily hybrid, composite nature of black art. The imposition of cultural forms from outside of Africa; the encounters with other forms that took place among those who were transported and displaced outside of Africa; the cross-pollination of forms brought about by migrations within Africa and encounters within the enslaved populations—all of these contact zones would have brought about a mingling of different spiritual traditions, cultural practices, and life philosophies.

Another way to think about it is that some of the techniques Morrison saw in white modernist writers also appeared in black forms such as jazz—we just don’t always call them modernist. I say in the book, for example, “Incompleteness, fragmentation, irony, and tragicomic feeling are the shared notes, or overtones, between modernist techniques and the black music of The Bluest Eye.” Simply by recognizing the historical synchronicity and formal resonances between disparate cultures, and then using those myriad composite traditions in her own work, Morrison completely reinvented the novel.

JC: How has Morrison’s work influenced your own fiction? (You mention, for instance, that in The Old Drift, your first novel, “a swarm of mosquitos by the banks of the Zambezi River narrates the tale,” not unlike her animistic approach in Tar Baby, and you also riff on a graveyard scene from Sula.)

NS: I often engage directly with her individual works like this: I allude to, try my hand at, or write back to particular Morrisonian lines or ideas or formal techniques. More broadly, I would say that reading Morrison over the course of my life as a fiction writer has given me the courage of my artistic convictions. She inspired me to be bold, to be experimental, to buck expectations, to make the reader work, to make the reader cry, to be politically irresponsible, to refuse respectability, to be playful, to be an adult, to be difficult, to insist on being taken seriously.

JC: Has Morrison’s work inspired your criticism?

NS: Of course. Her arguments have been crucial, especially to how I analyze race in art. As I say in my chapter on Playing in the Dark, which argues that Morrison’s critical mode is “shade”: “As a critic, I have conceived several essays under the cover of shade. I gave the Pixar movie Soul a read for its breezy use of racialized tropes—slavery, animality—to depict an existential crisis about the afterlife. I dragged Mohsin Hamid’s recent speculative novel about a white community that undergoes the great tragedy of becoming black.” And of course, Morrison’s critical style—entwining the personal, the political, and the analytical—along with her two-fold aim to be both rigorous and accessible set the template for how I wrote On Morrison.

JC: Your chapter on Beloved offers a quick summary of the neo-slave narratives—”fictional account[s] of slavery written in modern times”), including Margaret Walker’s 1966 historical novel Jubilee, Gayle Jones’s Corregidora (1975), the 1976 Flight to Canada by Ishmael Reed, who coined the term; Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979), Charles Johnson’s The Oxherding Tale (1982) and, more recently Max Ruff’s Lovecraft Country and Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, both published in 2016. You also make it clear that slave narratives by Frederick Douglass, Olaudah Equino and William Wells Brown had to navigate a “paradox of representation,” including the fact the “an exposé of the horrors of slavery risked subjecting the enslaved to the voyeuristic white gaze that fed on salacious scandal, what we now call trauma porn.” This helps illuminate how Morrison chose to invent a ghost story—a haint story—based on a factual infanticide—in which she can show “what happens internally, emotionally, psychologically, when you are in fact enslaved, “ and how she felt responsibility for “the woman I’m calling Sethe, and for all the others unburied, or at least unceremoniously buried…” After all the years in which you have studied, written about, given talks about this novel, what do you think made it possible for Morrison capture Beloved, and “the atrocious history she embodies?”

NS: Morrison conceived of Beloved as a three-part project; it is the first volume of a trilogy, her original plans for which are held in the archives at Princeton. It is fascinating to compare that proposal and comments about the works-in-progress with the eventual books: Beloved (1987), Jazz (1992), and Paradise (1997). In her work as an editor, she had come across some historical documents, each of which had raised a philosophical question for her: “the nature of the beloved,” which she defined as the part of us that is “reliable, that never betrays us, that is cherished by us.” She explored this question under three different frameworks: familial love under slavery, romantic love in an era of freedom, spiritual love in a moment of political utopianism. In this sense, I see Morrison’s Beloved trilogy as her extended version of Plato’s Symposium—a work of historical fiction that is also a philosophical meditation on love. What is remarkable is that each of the three parts of the project emerged for Morrison with its own antecedent genre: Beloved and the ghost story; Jazz and jazz; Paradise and the epic.

So what changed between the early proposal and the masterful works that she published? Tone, style, and possibly subject matter—there is an argument to be made that the third volume she originally planned eventually became her novel, Love (2003). For instance, the nature of the ghost was very different in Morrison’s plan for the books—Beloved was to be a wise-cracking haint who ages slower than humans and was meant to reappear in the second two novels set in later periods. But I think when Morrison began to do the research for the first book, and to confront the horrors of slavery that had long been veiled and continue to be subject to censorship, she had to adjust her plan—she adopted a lyrical, elegaic, sermonic tone; she used modernist fragmentation and theories of consciousness to depict the inner lives of the enslaved; she wrote a ghost story less about gimmicky jump-scares than about historical haunting.

Art doesn’t begin with a choice of subject matter or “content”; it first comes to us as an idea, an inspiration, the spirit of a question; our job is to seek and then perfect the right shape to carry it.

In a way, Morrison didn’t choose to write a story about slavery; it chose her, and she followed its lead—its history, its implications—to find its form. I find a crucial lesson in this. Art doesn’t begin with a choice of subject matter or “content”; it first comes to us as an idea, an inspiration, the spirit of a question; our job is to seek and then perfect the right shape to carry it.

JC: When did you first notice the intriguing connection between Beloved and A Mercy, one of Morrison’s “late reprisals,” as you call her “elder literary works.”

NS: I am indebted to my former colleague and friend, Stephen Best, for the seed of that idea. His brilliant essay, “On Failing to Make the Past Present,” argues that A Mercy is Morrison’s riposte to her own project in Beloved—or at least to the reparative archival movement it spurred. Upon rereading the novel to teach, I realized that she deliberately reverses or rearrange the terms of many of her previous novels; I describe this as an anagrammatical style, riffing on the idea (which I got from my current colleague and friend, Neel Mukherjee) that A Mercy is almost an anagram of America. Most poignantly, she considers a counterfactual to Sethe’s infanticide in Beloved: what if, rather than kill her daughter to prevent her from being enslaved, the mother made sure her daughter was sold into slavery in order to save her from a worser fate? Morrison walks us through the agonizing implications and consequences of the other choice in the ethical bind.

JC: In addition to her award-winning novels, Morrison had an extraordinary influence in shaping literary culture, as a groundbreaker and path opener, editor and teacher, cultural critic and spokesperson for literary freedom and the role of the artist (all aspects of her presence I highlighted in nominating for the National Book Critics Circle’s Sandrof award for lifetime achievement, which she won in 2015.) How did you weave these aspects of her life into On Morrison?

NS: I consider some of these sides of Morrison in my introduction, “On Difficulty,” which takes up her sharp wit, her refusal to suffer fools, her contrarian politics, and crucially, her commitment to black aesthetics. And I talk about some other sides to her in my conclusion, “On Monuments,” which is about how I think about approaching a writer of such eminence, one whose image is still being fixed, concretized, and polished as a testament to black excellence.

But the rest of the book focuses on her writing, with very close attention to her formal techniques. Morrison was very anti-biography. This is true when it comes to how she wrote characters, given that she felt real people had a kind of “copyright” on them; when it comes to how she taught students (“I don’t want to hear about your little lives”); and when it comes to how she conceived of her own life: she canceled a contract for a memoir and insisted her papers be stored “someplace where no one can write some stupid biography.” I confess, I sympathize.

I only included elements from Morrison’s life in my book when they informed my analysis of her writing: I cite the works we know she read in college and graduate school; the works we know she edited when working at L.W. Singer and Random House; the works we know she engaged with in her criticism and through the allusions in her fiction; and so on. I sometimes refer to feelings and attitudes and beliefs that she expressed in interviews to frame my sense of her aesthetic purposes. But as I say toward the end of the book, “I would much rather play in the shade with her words and ideas than stand dazzled by the Klieg light of her celebrity.”

JC: What are you working on now/next?

NS: I have a contract with Hogarth to publish an essay collection, so I’m working on some possible new pieces to include: on race and robots, on nonbinary texts, on what I call “black relativity,” on death and friendship, and on the politics of refusal. I also seem always to have a handful of novels in my head, some set in Zambia, some in the U.S., some conceived as early as 2002, others as recently as this past month. Last summer, I revised and finished a full draft of a novel about a black home care nurse in DC—the idea first came to me in 2008. I’m looking forward to working next on either a comic family drama, a novella about a religious figure from Zambian history, or this new one: a political thriller/ spy novel about MI5 and Africa.

__________________________________

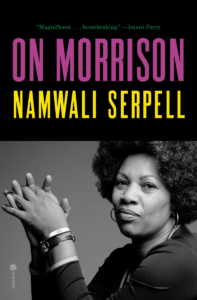

On Morrison by Namwali Serpell is available from Hogarth, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.