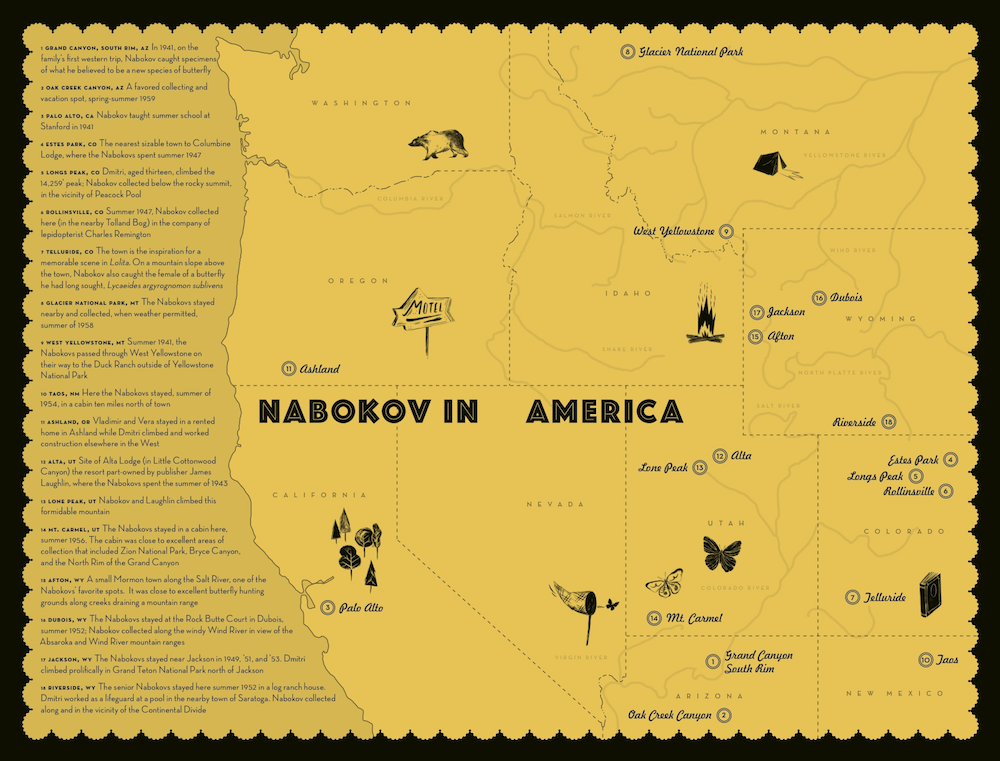

On about July 15, 1958, an advance copy of Lolita caught up with Vladimir and Vera in Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta. They had seen a piece in The New Republic that had spoken of Nabokov in terms that they welcomed, in terms of, as Vera put it, “true greatness.” Lolita publication day was now only weeks off. Not in much of a hurry, but tremendously excited, they turned east. They stopped at Devils Tower National Monument, in northeastern Wyoming. Their cabin was across the road from the tower itself, which looked to Véra like a giant conical ice cream treat (in France called plombières) that “has just begun to melt at the base . . . purplish-chocolate-colored.” When the weather was warm Vladimir collected butterflies.

“Sheridan [Wyoming] was engrossed in a big rodeo,” Véra wrote in the diary she kept of those days. She hated seeing “poor cattle mistreated,” but the local event was causing a stir: “We were almost driven off the road repeatedly and had to stop for cars passing other cars to get back in their lane—all of them . . . with horses in trailers.” They saw “two trucks in collision—no one hurt but the vehicles; and, on the shoulder of the road, a cowboy, all decked out . . . dismally changing . . . a tire.”

By early August they were in New York. Walter Minton, president of G.P. Putnam’s Sons, the Lolita publisher, was throwing a press reception at the Harvard Club, and the Russian-born author was the celebrity attraction. Minton was an “excellent publisher,” Véra decided, someone who was spending freely on “beautiful ads,” and the book his house had produced was itself beautiful, with a cover that the Nabokovs found tasteful (containing no image of the soon-to-be-notorious little girl). On August 18 Minton sent them a telegram:

By early August they were in New York. Walter Minton, president of G.P. Putnam’s Sons, the Lolita publisher, was throwing a press reception at the Harvard Club, and the Russian-born author was the celebrity attraction. Minton was an “excellent publisher,” Véra decided, someone who was spending freely on “beautiful ads,” and the book his house had produced was itself beautiful, with a cover that the Nabokovs found tasteful (containing no image of the soon-to-be-notorious little girl). On August 18 Minton sent them a telegram:

EVERYBODY TALKING OF LOLITA ON PUBLICATION DAY YESTERDAYS REVIEWS MAGNIFICENT AND NEW YORK TIMES BLAST THIS MORNING PROVIDED NECESSARY FUEL TO FLAME 300 REORDERS THIS MORNING AND BOOK STORES REPORT EXCELLENT DEMAND CONGRATULATIONS.

Sales figures were immediately large. In the first four days, there were 6,777 reorders from retailers running out of copies, and by the end of September Lolita was number one on the New York Times bestseller list, where it remained for seven weeks.

At Minton’s party Vladimir was “a tremendous success . . . amusing, brilliant and—thank God—did not say what he thinks of some famous contemporaries,” Véra recorded. This party was a foretaste of gala events to come in Paris, London, and Rome at which the author and his demurely glamorous, long-necked wife, with her snowy hair and comme il faut outfits (a black moiré dress and mink stole in Paris), graciously displayed themselves. The sales and succès d’estime of Lolita made Nabokov a New World celebrity. He had squared the circle, written a challenging work that was also an alluring sex book, still, at the time of its U.S. publication, under legal restriction in Britain and France. F. W. Dupee, a professor at Columbia and a freelance critic, wrote early reviews that called Lolita a “magnificently outrageous novel,” also a “little masterpiece,” also “a formidable addition to popular mythology.” By mythology he meant that other stories had already attached to the novel’s story. The main one was the tale of the book’s path to publication: how respectable New York houses had all fled from it, how the brilliant author had had to send his manuscript to Paris, where a semi-pornographer had taken it on, and how the shunned work was now a “prodigy of the . . . business,” “not only a novel but a phenomenon.”

Those who now embraced Lolita, Dupee wrote, included “all the brows—high, middle, and low,” categories of reader not used to “celebrating together.” The book had had “the luck to make its American appearance at just the right moment. The state of literary feeling . . . has been undergoing . . . a change here during the past year,” and Lolita had “both profited by the change and helped to crystallise it.”

Dupee was trying—more successfully than any other early commentator—to locate what was large in the little masterpiece. The author was an unlikely source for a change in national temper, Dupee thought: he was a foreigner, to begin with, serenely out of step with a postwar turn that Dupee deplored, a “gone native” movement that believed in sturdy local traditions and that hoped to place morality at the center of American discourse. “Into this situation Nabokov failed to fit at all.” Nor was Nabokov’s pre-Lolita reputation promising—“admirable but rather scattered” work that “seemed to belong to the . . . obsolescent category of avant-garde writing.”

Dupee, a mordant, stylish person who knew how to enjoy himself, found a rich new taste in the book. “It has helped to make the fading smile of the Eisenhower Age give way to a terrible grin,” he wrote, and this death’s-head imagery might have been the best way he could find to suggest the wrenchingly disparate moods of the book, moods of “disgust and horror” but also of a weird, writhing mirth, darkly knowing, scathingly sophisticated. (“The book, they tend to say, is not pornography, having no four-letter words in it. And again Humbert Humbert can be heard to laugh.”) Dupee had been waiting a long time to catch this new tone, he implied. Lolita was a book “too shocking for any great tradition to want to own,” but he, Dupee, owned it; it answered something needful in him.

On September 13, a friend phoned the Nabokovs to congratulate them on what he had just read in the Times: that movie rights had been sold to Stanley Kubrick for $150,000. That was a phenomenal sum in 1958. Along with royalties soon to begin flooding in, it was far more than Nabokov had earned from all his previous work as a professional writer during forty years. In her diary Véra noted, “V. supremely indifferent—occupied with a new story, and with the spreading of some 2000 butterflies.” Probably he was not indifferent. The page-a-day preserves the mood of those weeks; Vladimir thought that the account that Véra was writing was “important” to have, a kind of scientific field note, but it was his splashy success (and hers), hard-won after a long struggle, and it mattered to them, mattered deeply. Inquiries from “movie companies and agents, letters from fans etc.” kept coming, along with requests for interviews. All this “ought to have happened thirty years ago,” he wrote his sister in Switzerland, adding, “I don’t think I shall need to teach any more.”

A team from Life magazine came to Ithaca, led by staff writer Paul O’Neil and photographer Carl Mydans. Véra’s account of the visit is amused but quietly thrilled—both Nabokovs knew the meaning of being portrayed in Life’s pages. “To think that three years ago,” she wrote, “people like Covici, Laughlin, and . . . the Bishops strongly advised V. never to publish Lolita, because . . . ‘all the churches, the women’s clubs [would] crack down on you.’” Now a Mrs. Hagen from the local Presbyterian church called to ask if Vladimir would address their women’s group. Delicious irony! Yet the others had not been wrong: to have published four years before would have been to serve up another victim to censorship, probably, Lolita and its author sharing the fate of Edmund Wilson with his novel Memoirs of Hecate County. The book’s having gone first to France, where its louche publisher had fought early censorship battles, had contributed to the cultural shift that F. W. Dupee praised. Lolita had birthed its own birthing.

They “could not believe our ears,” Véra wrote when, on Sunday, December 7, they saw on The Steve Allen Show a skit about “new ‘scientific’ toys. Last item: doll-girl who can do ‘everything, oh but everything.’ . . . ‘We shall send this doll to Mr. Nabokov.’ We both heard it distinctly.”

And on Dean Martin’s show, the singer explained that he had gone to Vegas but had had nothing to do because “he did not gamble. So he sat in the lobby and read . . . children’s books—Polyanna, The Bobsie Twins, Lolita.”

Furthermore, “In his first show of the new year . . . Milton Berle opened with . . . ‘First of all let me congratulate Lolita: she is 13 now.’” And Groucho Marx was heard to say, “I’ve put off reading Lolita for six years, till she’s eighteen.”

For his own first TV appearance, Nabokov went to Manhattan to be filmed for a Canadian show, hosted by CBC personality Pierre Berton and featuring scholar-critic Lionel Trilling, an influential fan of Lolita. Véra and son Dmitri were in the studio. Dmitri felt proud of his father, and Véra thought that her husband “spoke beautifully.” “Then the warning came: Stand by! . . . three minutes left . . . two . . . one . . .” The stage set visible in the surviving videotape suggests a writer’s study, or a Vincent Price movie version of one, with a candelabra on a table, a sofa, statuary, books on shelves. The celebrity novelist has a rumpled look. At fifty-nine he has a thick, powerful neck and is mostly bald, but unwrinkled. Trilling, a slighter, younger man, looks older, troubled, brooding. He smokes throughout.

“On they were,” Véra recorded, and her hero proves an “ideal guest” (so the producers later said), magnanimous toward those willing to try his book while dismissive of “bigots and philistines.” He retails stock Nabokovian ideas. He is not interested in producing emotions in his readers, nor in filling their heads with ideas. “I leave the field of ideas to Doctor Schweitzer and Doctor Zhivago,” he says, Doctor Zhivago, recently published, being a special irritant to Nabokov, who considered it trash and its publication in the West an obvious Soviet ploy. (Supposedly anti-Communist, it did not go far enough, the Nabokovs felt.) Instead of emotions, Vladimir says he wants readers to get “that little sob in the spine,” the flash of aesthetic bliss, when reading his work, and the chat-show host cannot let this statement pass: he asks Trilling if he felt no emotions when he read the book, and Trilling says, “I found it a deeply moving book. . . . Mister Nabokov may not have meant to move hearts, but he moved mine.”

Nabokov denies any satirical intent. He is not criticizing America, “holding up the public abuses to ridicule.” Trilling replies, “But there is an underlying tone of satire through the book,” and, “we can’t trust a creative writer to say what he has done; he can say what he meant to do, and even then we don’t have to believe him.”

Both men are a bit sententious. This was the only filmed interview, as well as the last interview of any kind, for which Nabokov did not insist on the submission of all questions in advance, thus it provides as unscripted and in vivo an impression of the author as exists. Even so, he has a bunch of cards in his lap on which he has written phrases; when he can, he quotes himself.

Nabokov grins behind Trilling’s back. He grins when the critic says that we can’t trust writers to do what they say; there is at least the possibility that he is grinning also because he knows that much of the power of his novel is due to a social critique, a deep and excoriating one, a critique that has caused “terrible grins” to appear on many American faces. A darkly dissident cultural skepticism comes into play with Lolita. The extent of it will become clear over the next decade and a half, and tonal similarities abound—in the movies, in productions like Hitchcock’s Psycho (1961) and Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964), and in literature and in other cultural domains with the roiling intensity that is now associated with the term “the sixties.” Alert readers pick something up. The suburban world of Ramsdale and Beardsley, Charlotte Haze’s taste-free house, the forties roadside reality of motor courts and mindless miles racked up in a car: Nabokov had done his homework, and for him to insist on an imaginary America, an America “just as fantastic as any inventor’s,” conjured in his workshop and not based on the observable world (“It was fun to breed her in my own laboratory,” he says), came across as fussy and false.

He had looked around him and recognized a curious, half-asleep people—a perky populace with gloomy secrets, inhabiting a magnificent landscape that it tended to crap up, prone to stifling social norms best depicted via caustic comedy. Gunplay would arrive in the last act, as it did in so many of the nation’s stories. Sex would be the springboard for all else—non-standard, indeed perverted, sex, because the country in its youthful aspect was fresh and sexy but also strapped in with prohibitions. The author swore he had no reforming purpose, did not wish to cause any sort of “awakening,” and in this he can be trusted: America for a writer of his kind was perfect as found.

Trilling maintains a dignified stillness. Nabokov in contrast twists, lunges, and half-reclines on the sofa, his ovoid head angling and swiveling. He grins again when Trilling, trying to explain what he finds “shocking” about the book (“a young girl, someone . . . usually preserved from the sexual attentions of men; a very young girl, of twelve as I recall”), seems to be fighting a grin of his own, and Nabokov casts a look at the moderator: “Is he not licking his lips, sir? Oh, I fear your distinguished critic has read my book in the wrong way, just a little!”

Peter Sellers’s scrutiny of this documentary footage, as he prepared to play Clare Quilty in Kubrick’s film—and his liberal quoting from it, in the three roles he played two years later in Dr. Strangelove—is hard to gainsay. Dr. Zempf, a school psychologist (Quilty in disguise), borrows Trilling’s biting way with certain loaded words (“sex,” “sexual”), and Trilling’s way with a cigarette, reminiscent of Edward R. Murrow’s, includes both the usual forefinger/middle-finger wedge and a much more peculiar (in the American context) thumb/forefinger grip, the smoking tip pointing upward. Sellers works brilliant changes on this when Dr. Strangelove, in the later movie, smokes a cigarette as he explains the Doomsday Machine. The pomposity of the whole encounter seems to have galvanized Sellers and his director: the two clubby men of letters talking about sex with a comely child, almost giggling despite themselves; Nabokov modestly admitting that, yes, he is an expert on clinical pedophilia and on butterflies, in addition to being a great writer; Trilling with his hollow-eyed stare, looking like a man who has just gotten bad news from his gastroenterologist.

Both men are also appealing. Trilling loses his lugubriousness when he talks about the novel, which has truly excited him: he has been touched by the girl’s plight, by the tragic trajectory, by passages of sad tenderness. We suspect he even laughed at the wicked parts. And Nabokov connects, despite all his squirming. Even on this comical stage set, typecast as a condescending aesthete, he peers repeatedly from behind the mask, wanting to make contact with whoever may be out there. Shamelessly he plays the great man, but every now and then a beautiful, boyish smile breaks out on his big, mobile face—vulnerable, wholehearted, it is the smile of someone wanting to let you in on the joke, someone himself never far from helpless laughter.

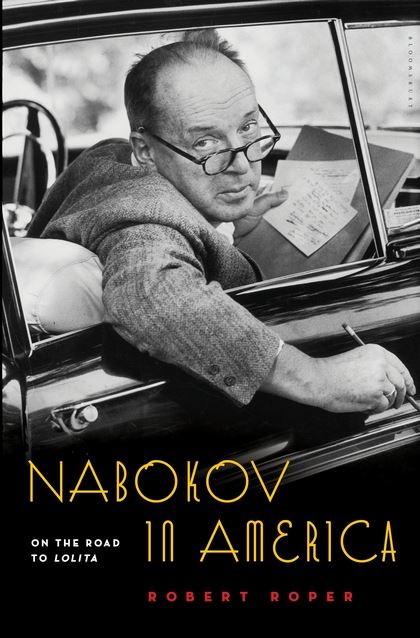

From NABOKOV IN AMERICA: ON THE ROAD TO LOLITA. Used with permission of Bloomsbury USA. Copyright © 2015 by Robert Roper.