Mystics, Martyrs, Bats, Blood Sonnets: Seven Poetry Collections to Read in September

Rebecca Morgan Frank Recommends Susan Howe, Gary Jackson, I.S. Jones, and More

Poetry Readers, what a month. Copper Canyon delivers a much-anticipated one-two punch with Richard Siken’s I Do Know Some Things and Natalie Shapero’s Stay Dead. Our most recent U.S. Poet Laureate, Ada Limón, releases her New & Collected, Startlement, with Milkweed, and Knopf drops compelling new collections from Kevin Young (Night Watch) and Rickey Laurentiis (Death of the First Idea).

Did I mention there’s a 45th-anniversary deluxe hardcover edition of Sharon Old’s debut, Satan Says, complete with an introduction from Diane Seuss? Those are some of the more familiar titles from the towering stack of September 2025 poetry, so read on for a few surprises, including superheroes, mystics and martyrs, along with an overdue Selected Poems and a debut that conjures a boi Cain and her sister Abel.

*

Susan Howe, Penitential Cries

(New Directions)

I spotted Susan Howe in a trendy shoe store in New York years ago when I was a graduate student. It was like seeing a rare bird land and being surprised that it not only flies but touches the ground. But isn’t that part of what makes Howe so compelling, her thrilling ability to be out in a field beyond aesthetic binaries, simultaneously pushing and merging visual, sonic, and genre boundaries?

Penitential Cries opens with a ranging extended essayistic poem: “Let mind wander over prehistoric combat. All the kingdoms. Egyptology Europathy Sinology cold and hot then annihilation, cast out land of spirit-world anterior to creation even fishes / some indecipherable leaping.” This wandering and leaping moves among mystics such as Marguerite Porete and Johannes Kelpius, touches on Jean Cocteau and Wittgenstein and “Widows and Pariahs,” “for to be one or both is to be anonymous in soft rain on a quiet street waiting quietly alone.”

For this speaker, “Frailty means nothing Night of my soul, not yet forced to go paperless, branches and brilliance, willing to run the risk of whistling dust beside lists of other authors” and “Enjambment tipped in with wings extended / before forgetting the intellectual part not even two syllables not the least sting in the arm—sometimes even exultation.”

“Left the body,” begins the sparse final poem, “Chipping Sparrow,” but we’ve been in the mind all this time, including parsing the signature Howe collage, with its snippets of texts overlapping, crossed out, turned. This collection marks more than fifty years of making and publishing by Howe, and she can still surprise and yes, exult.

Gary Jackson, small lives

(University of New Mexico Press)

“Even/in prayer, your own body comes last.” Meet the inner lives and challenges of The Invisible Woman, The Telepath, The Willpower Man, Black Goliath, Beast Boy, and of course, the characters “we/us/them” and “countless others” in the pages of small lives, the latest collection from Gary Jackson.

Jackson turns to the prose poem to extend the psychological depths and lyricism of his sophomore collection, origin story, drawing more directly on his interest in Black comics and superheroes as co-editor of The Future of Black: Afrofuturism, Black Comics, and Superhero Poetry.

The characters wrestle with post-traumatic stress, loneliness, and the adversities of their missions: “The Invisible Woman Goes to a Party” begins, “One line won’t erase it,” and in “Telepath,” the narrator “touches the man’s mind and reorders his blood and fury into lines she can read,” for “she must sift through his memories which are like swimming in shit: difficult to wash off. She tells herself this is good, useful work.”

The poems continue to build, question, and mark their own historical and cultural context: “stranger things,” begins, “I’ve seen white folks do the strangest things….” The life of these poems expands beyond earth, full of the threats, and lights, here and beyond. In “acts of kindness,” “You disconnect each child from their compartment, too young to understand what their country is doing to them under the small lights of indifferent stars.”

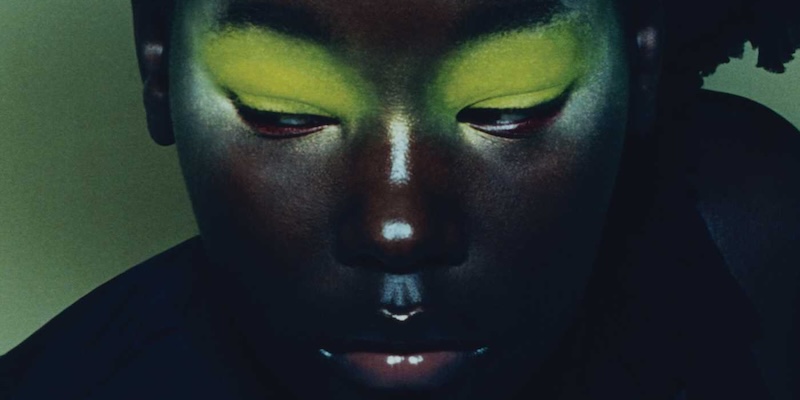

I.S. Jones, Bloodmercy

(APR/Copper Canyon Press)

In NPR’s recent summer 2025 Here and Now book club, they addressed the pros and cons of reimagined stories in their discussion of Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead and Percival Everett’s James. Novels only, of course, but as poetry readers know, poetry is rich with such moves—or lousy with them as the “con” folks might argue.

American/Nigerian poet I.S. Jones, the latest winner of the APR/ Honickman First Book Prize, offers up an original and robust new take on Cain and Abel; this time, it is two sisters who once were one: “You reach for my hand & we become one erratic body: two-headed, four-legged, barefoot galloping….” Cain, the “daughterprince,” “best boi” who “boy’d better than the other boys” and “boylaughed at the other girls,” “and the many animals slain beneath me. / then the other girls” faces the hard turn to womanhood: “Oh Father, I have been a girl all my life….”

Meanwhile, Abel laments her role as slaughterer: “hunger is a savage god all bodies must kneel to/ and it’s hard to desire anything you’ve made submit” and longs, noting, “yesterday, a beautiful girl put a red ribbon in my hair, meaning were to meet in dark among the firs.” Jones delivers a propulsive debut.

Lex Orgera, Agatha; poems for the bodies in revolt

(Jackleg Press)

“Aviation is / women’s work / so high up, we’re planetary.” Lex Orgera’s opening section of three poems, “Invocations,” sets the lyrical stage. Then Agatha enters: Agatha, the legendary martyr, tortured for saying no. “Silly little nipple squeezer. Woodcut Geezer. / How nonchalant in my torture,” opens the ekphrastic “Agatha Before the Earthquake.”

“What you don’t see,” Agatha continues, “I scared him off, I made a pencil out of him. /Into the fire no less!” Elsewhere, “No one wants to touch me because I’ve become a finch!” Agatha sees clearly: “I became the church’s duty, a native hen-peck— /to murder or martyr, doesn’t matter— on the rolling hills of the cross.”

Her legacy drives the collection, weaving in and out, threaded into presence, as outcast—in a poem about Catholic school, the speaker concludes, “To be a misfit in the world is to be welcomed into the Kingdom”—and as marker of the mind beyond, whether that of the speaker’s father who “hallucinates fingers in his dinner plate,” “his language beyond language,” or, in a series on called “Concussion Diary,” “Fifty needles in my eye. / The front door to another question.”

And “Maybe I’m not alive / except in my bruised mind.” Agatha persists, creates, needles. Orgera, a poet whose most recent book is the notable memoir Headcase: My Father, Alzheimer’s, and Other Brainstorms, is a writer to have on your radar.

Camille Ralphs, After You Were, I Am

(McSweeney’s)

Hold onto your hats as U.K. poet Camille Ralphs speaks back with wit and devotion to a who’s who of mystics, theologians, philosophers—Rumi, Herbert, Donne, Mechthild of Magdeburg—as she rewrites? Revisions? Reduces? prayers and poems in the opening section “The Book of the Common Prayer.”

In the collections’ other sections, she takes on a seventeenth-century English witch trial, the Pendle Witches, and the “spiritual diary” of mathematician/astrologer John Dee. Ralphs is all-in with these projects. She’s having fun: after all, she opens the collection with invocation, from a parody of Herbert: “Come, my Motorway, my Equals Sign, my Higher Race, / such a Motorway as wheels with stars,” to, a few poems later, her “Veni Sancte Spiritus”: “Come, pop-ology of psych, / beam yourself into us like / headlights through light-headedness.”

Then there’s her “Ecclesiastes 3: 1-8”: “a time to be a crony, and a time to be a crone.” The Pendle Witches who went to their death speak up in Ralphs’ own play of tongue: “In words, in images I came / I went/ In clay, I fashunn’d… Who? Man? Hare?”

Ralphs’ own fashioning is driven by a delight in sound, and for those who would critique the overriding wit, there’s condemned Jane Bulcock, “And we’re damned if we do; and we,re certainly damned if we don,t.”

Martha Silano, Terminal Surreal

(Acre Books)

From the first pages of this posthumous collection, Martha Silano lets us know that this is not a sober finale, not a familiar self-elegy: these poems assert and sting with a voice that is very alive and well, thank you very much. Silano is invitingly conversational.

“Flying Rats” begins “Actually? You do not have to be good,” following an epigraph, “apologies to Mary Oliver.” “When I’m on the Bed” continues into the first line—”called death. I hope” and then subverts our expectations by transplanting us into a visit to an Italian restaurant. Her vibrancy holds steady, and it’s hard to say which moment will get you in the unsaid. In “Wake-up Call,” we learn “My first word was. Duck.”

And here we are, reading her last words. I never met Silano before these pages, and I am grateful to listen to this distinctive voice singing on. Rest in peace, Martha Silano.

Patricia Smith, The Intentions of Thunder: New & Selected Poems

(Scribner)

It’s rather surprising that we have waited this long for a selected poems from Patricia Smith. The Intentions of Thunder delivers “hits” and unexpected moments for new readers and long-time fans, and it is a testament to Smith that the hits come from across all eight collections, including “Skinhead” from her second collection, 1992’s Big Towns, Big Talk, and “Hip-Hop Ghazal” from Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize winner Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah (2012).

Excerpts from Kingsley Tuft winner Incendiary Art and National Book Award finalist Blood Dazzler serve as reminders of how Smith’s later collections—as well as the newest, Unshuttered, in which the poems are in conversation with old photographs—read cohesively, projects sometimes akin to long poems.

Tucked in the middle of this Selected are some early uncollected poems, including the stark “Blood sonnets”: “I pried open the thin wobbly back/ of a record cabinet and crammed / my underwear inside. My mother had told/ me nothing about my body, damned,” and “Post-Racial”: “When I was four my nana wrapped around me, whispered lynch directly into my ear….”

The collection’s finale of newer uncollected poems showcase Smith’s magic touch with the sonnet crown, particularly the powerfully orchestrated “Salutations in Search of,” with its skilled crescendo of address.

Rebecca Morgan Frank

Rebecca Morgan Frank's fourth collection of poems is Oh You Robot Saints! (Carnegie Mellon UP). Her poetry and prose have appeared in such places as The New Yorker, Ploughshares, American Poetry Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is an assistant professor at Lewis University and serves on the Board of Directors of the National Book Critics Circle. She lives in Chicago.