My Years of Living Dangerously: On Late-Stage Catholicism, Lying, and Communion

Danielle Henderson Looks Back at Her Religious Upbringing

We’re not a religious family in the traditional sense. I’ve only seen my family genuflect when boxes of Entenmann’s pastries are on sale two-for-one at the Grand Union, and 60 percent of us were born so far out of wedlock our birth certificates list “who cares” in the space where you indicate the father’s name. Christmas was a time best spent ripping pages out of the 300-pound Sears catalog and begging for thousands of toys that would never make their way under the tree; Easter was the season for eating tie-dyed egg salad for a week straight to help revive you from the self-administered, candy-induced diabetic shock of your overflowing Easter baskets. Who rose from the what? Pass the M&M’s.

I was baptized in the Catholic Church a few months after I was born and didn’t step foot in a church again for seven years. They were big on protecting the soul, but there wasn’t much God in my life following my baptism, aside from the casual way every adult in my family took the Lord’s name in vain every ten seconds. Like all black families raised in the jive-talking 70s and politically oppressive 80s, “goddamn” was the most widely used descriptor of all things animal, vegetable, or mineral.

Though sometimes used aggressively, it was primarily a gentle way to indicate the world weariness and overall exhaustion cultivated deep in the bones of all middle-aged black folks. It filled a space, and your job was to figure out how to read between the lines of what each “goddamn” actually meant. “I said pass the goddamn salt” meant you were tired after a long day, certainly too tired to repeat yourself. “Do you know where my goddamn gloves are?” was code for “Which one of you moved my stuff after I expressly told you not to move my stuff?”

The rapid-fire, multiple wielding of “goddamn” was a threat level-red situation, a clear sign that you had just pushed someone to the limits of their sanity. It wasn’t unusual for my grandma to condemn me straight to hell for not letting her goddamn play the goddamn Nintendo she goddamn bought for these little goddamn motherfuckers. It was her expletive-laden form of praying that someone, anyone, would give her the strength to keep from murdering me for trying to level up on The Legend of Zelda when it was clearly her turn. When she dies, I will make sure her tombstone simply reads:

goddammit, i told you kids to leave me alone

We were a baptized bunch, but regular church attendance was never on the menu. My grandmother spent her Sunday afternoons chain-smoking foot-long Carlton 120’s and yelling at the Jets, Giants, Mets, or Knicks to throw, kick, punt, or pass whichever ball was in play. My grandfather open-mouth snored loudly in the armchair next to her, shifting slightly every time she yelled, “Shut up, Jack,” his snoring apparently more irritating than her exasperated wails. He usually went back to sleep quickly, patiently waiting for her to calm down or just give up so he could change the channel to WPIX and watch one of the Westerns that streamed all day. If Sunday was the Lord’s day, we were only taught to pray to the gods of the split-finger fastball and John Wayne.

Thinking I’d miraculously skipped out on all manner of religious instruction, you can imagine my surprise when out of the blue my mother informed me that I had to attend church school in preparation for my communion. “Don’t forget to go with Erin and Mrs. Garrett after school on Tuesday,” she said nonchalantly one day as she mixed a jug of powdered milk at the kitchen counter. “You’re going to church school.”

*

Holy Rosary was a small stone church on Windermere Avenue. It reminded me of the type of house you would see in a fairy tale, an unassuming place where the townspeople lived. The neighborhood was quiet; if you kept walking down the street, you would hit the top of the lake.

The schoolroom was just a room in the basement, filled with small plastic chairs lined up in rows. The teacher, a doughty woman who was likely a volunteer, made us all sit down. We instinctively knew to be quiet, since “school” was in the title, but, as a kid who never went to church, I had no idea what else was about to happen. After the teacher handed out the pink catechism books, we were invited to go to the wooden booth to confess to the priest. I sat in the dark box and was startled when the small rectangular screen slid open next to my elbow.

Like serial killers and three of the worst men I ever dated, I never really had a grasp on what I was supposed to feel sorry about.

“Hello, my child.” The priest asked me to call him Father, a word that sounded unfamiliar in my mouth, and confess my sins. As a book-obsessed seven-year-old I had absolutely no idea what he was talking about, so I did the thing that came naturally: I lied my ass off.

“Um, I broke my mom’s favorite mug,” I said confidently. “And how did that make you feel?”

“Uhhh… bad?”

“Say ten Our Fathers and three Hail Marys.” Well, that was easy.

Like serial killers and three of the worst men I ever dated, I never really had a grasp on what I was supposed to feel sorry about. Week after week, I filled the confessional with lies. I yelled at my teacher. I stole my best friend’s favorite toy. I kicked a dog. I punched my brother in the nuts. No one ever caught on, verified my story, or gave me more of a punishment than walking to a pew to chant a few quick Our Fathers on a plastic rosary. It slowly dawned on me: if I could lie and be quickly forgiven, there was nothing to stop me from actually doing some of the stuff I was making up. Catholicism flipped a switch and turned me on to a life of crime.

First, I stole a pack of purple jelly bracelets from Hanley’s Lotto, which doubled as a five-and-dime. Purple was my favorite color, and the bracelets were the most prominent status symbol of the first-grade set. Instead of buying them one at a time, I took the whole package and stacked them halfway up my arm. Within three weeks, I had a rainbow of stolen goods that I cleverly looped into a jump rope. I said a few Hail Marys and slept soundly.

My neighbor Kurt always teased me for being tall; after I learned that I could be forgiven for anything in confession, I started beating up him with gusto.

My days of lying and thieving lasted until my first communion. I had a loose grasp on what I needed to do in order to be communed aside from an agonizing day spent in Sears buying a miniature wedding dress replete with a tiny child-bride veil, but the fact that my whole family was coming seemed like a big deal.

My great grandmother, Sweetie Pie, came up from New York City wearing her finest daytime turban, her light skin offset by a pair of giant, dark sunglasses. She had a deep, croaking voice and spoke in a slow, quiet way that made her seem like the most glamorous woman I’d ever meet. It’s hard to imagine her sitting on a graffiti-filled subway and enduring a nauseating two-hour-long bus ride to get there when she clearly should have arrived in a crystal carriage powered by unicorns.

Sweetie Pie and Grandma talked on the phone almost every day, but she only came to see us a few times a year. She always carried a camera with her, the kind with the long flash cube attached to the top, and would read books with me for as long as I wanted. When the rest of the city family visited once a year, she drove up with them but hung out with us. While the other adults were in the kitchen cooking, playing cards, and drinking beer, Sweetie Pie was outside, listening intently to our instructions about which rock was a base for the game we just made up. She took pictures of us while we ran around; without her there to document it, the happier part of my childhood would be an unattainable memory.

My mom curled her hair into a Farrah Fawcett bouffant, covered her entire eyelid up to the brow in turquoise eye shadow, and wore a maroon, tapered jumpsuit under a short white blazer; she looked like a Rainbow Brite doll about to turn tricks. My grandmother was busy being choked by a shirt with so many ruffles I thought her skin would be permanently marked with undulating waves, but her Jheri curl was spritzed to high heaven, shining brighter than the safety reflectors on my bike wheels.

My grandfather wore the same thing he always wore—a thin plaid shirt with the top two buttons undone and a pair of jeans—but he deigned to put on a pair of shiny black shoes. My brother was also part of this communion and wore a tiny black suit with a white shirt and tie. There’s a picture of all of us standing in front of the church; without context, it looks like a hooker, her parents, and their madame are happier than ever to marry their youngest children to each other before they hand them over to the pope.

The ceremony was long and forgettable; legions of children marched up to the podium one by one and listened to the priest mumble something in Latin before he shoved a dry Styrofoam disc in their mouths and made the sign of the cross over his elaborate robe. The body of Christ tasted like construction paper and felt like a giant, doughy penny as it dissolved on your tongue.

When it was over, I asked my grandmother excitedly what was next. I was already planning my next attack on Kurt and wanted to know when I could come back to church to be forgiven for it.

“What do you mean, ‘what’s next’?” my grandmother said.

“When do I come back to confession?” I said.

My grandmother looked down at me, her mouth terse and one eyebrow raised. “Child, we’re not coming back here! We don’t have time to drive your ass to church every week.” She walked away briskly, barking at everyone to pile into the car so we could go home in time for her to catch the next game.

My communion marked the beginning of my soul’s salvation and the end of stealing. It was a relief—I had a hard time believing in God, and I was running out of stuff to make up in confession.

__________________________________

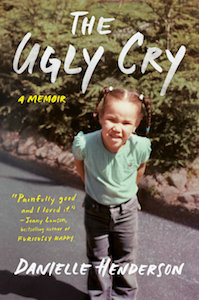

Excerpted from The Ugly Cry. Used with the permission of the publisher, Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Danielle Henderson.

Danielle Henderson

Danielle Henderson is a TV writer (Maniac, Dare Me, Harper House), retired freelance writer, and a former editor for Rookie. She cohosts the film podcast I Saw What You Did, and a book based on her popular website, Feminist Ryan Gosling, was released by Running Press in August 2012. She has been published by The New York Times, The Guardian, AFAR magazine, BuzzFeed, and The Cut, among others. She likes to watch old episodes of Doctor Who when she is on deadline, one of her tattoos is based on the movie Rocky, and she will never stop using the Oxford comma. Danielle reluctantly lives in Los Angeles.