My Year in Reading Children’s Books

Sara B. Franklin Recommends Cecilia Ruiz, Steve McCarthy, and Many More

It was the first of November, and forecast to dip below freezing overnight. Before school pickup, I went out to twist the last zucchini off the vine, and snap chard leaves off their stalks. It had snuck up on me, this hinge point of the year, it always does; the garden growing so fast, and my kids, too. It was time to put things to bed, to tuck in the corners of the year and ask, what have we made of the time, and what has it made of us?

I was startled, looking back, how alike, in its agonies, this year has been to the ones that preceded it. Widespread wildfires. Unchecked gun violence. More erosion of reproductive rights, trans rights and, with them, parental rights of trans youth. More and more people exiled from their homes, claims being made on the land by way of war in the name of the state, of god. It’s as if we’re stuck in some terrible, accelerating loop.

Things aren’t, it has become abundantly clear, going to “normalize.” Precarity is the state we have wrought. So how do we thrive, here, amongst the ruins? To turn the prism and reframe the essential questions, some go to prayer. I go to poetry. In times suffused with hatred, why not now, asks Natalie Diaz, go toward the things we love? How might we, Ross Gay asks, make honey here in the dark?

To translate such poetics into praxis, we’ve got to start with granular attention, start by noticing what our bodies feel, what they know.

Invisible Things (Andy J. Pizza & Sophie Miller, Chronicle) translates the practices of somatics and mindfulness into language and images that make sense to young readers. There are sensations and then there are feelings, Pizza and Miller write, and the latter can be can be bewildering, coming “one at a time or in a big, confusing jumble.” Sometimes a “BIG MOOD” takes hold, and it can be hard, in the moment, to discern if feelings are good or bad. “These Things are cool and kinda strange,” write the authors. Take, for instance, fear, which “can be a difficult Thing, but it can also be a helpful Thing. It reminds you to be careful. But when Fear stands in the way of things that could be good for you… that’s when you also need Guts.”

“Sometimes the things we care about the most, the things we never want to see gone, leave anyway.”

Mustering said guts is the subject of two of my children’s and my favorite books of the year. In Mr. Fiorello’s Head (Enchanted Lion), Cecilia Ruiz writes, “Sometimes the things we care about the most, the things we never want to see gone, leave anyway.” The story explores the experiences of loss and unexpected change via the whimsical metaphor of a man whose once lush mane dwindles to baldness, save three holdouts hairs. Embarrassment, shame, and nostalgia rear up in Mr. Fiorello. He tries in vain to recover the past before finally giving up.

“The day he began to accept what he had and let go of what he couldn’t control,” Ruiz writes, is the day things began to change. An upswell of emotion accompanies the shift; Mr. Fiorello weeps, unable to “tell if they were tears of happiness or grief.” But what he recognizes is that those three lingering hairs—and more so, his feelings about them—had been weighing him down. Life, Ruiz reminds us, is constant change. To resist this is to get stuck, to stagnate. At last, Mr. Fiorello “knew that the time had come to let new things take root, sprout, and grow,” and thus unlocked the door to his own freedom.

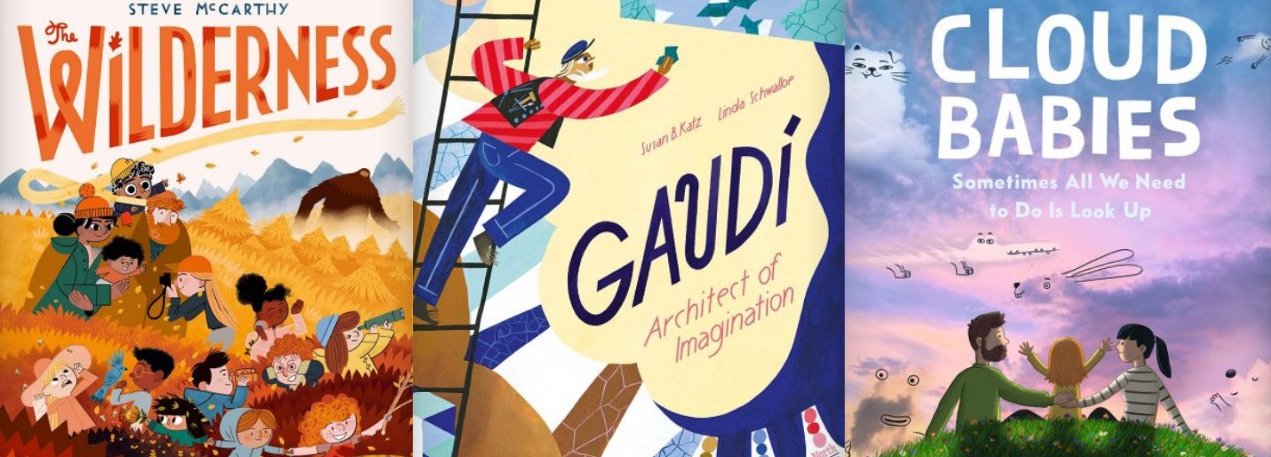

We often resist shedding that which no longer serves us. Most adults need more practice with letting go, and children need modeling and guidance from the grownups in their lives to learn how to do it themselves. The joint approach is narrated beautifully in Steve McCarthy’s Wilderness (Candlewick). The Vasylenko family is big (12 kids), hardy, rambunctious, and adventurous of spirit (and, while it’s never named, appears racially varied, as though bound not only—and perhaps, for that matter, not at all—by blood).

Papa Everest (as in mount) and Mama Mariana (as in ocean trench) and eleven of their children are thrilled by “wild things,” “wild places,” and “wild adventures,” but the same unknowns terrify one member of the brood, the frightened and bookish Oktober. He sees The Wilderness as a living monster; thoughts of them keep Oktober up at night. His mom and dad try to talk their child out of his fear, attempt to convince him to see things their way. But that, as all parents know, is a fruitless tactic.

Things take the time they take, wrote the late Mary Oliver. Megan Fernandes echoes the sentiment, ask what happened, wait, a revelation is slow. We owe ourselves, and our children, a little room and time. Oktober’s parents change tack, joining their child in his discomfort. “’It’s OK to be scared,’ said Dad. ‘I get scared, too. Scared is how you feel, but bravery is what you do.” “’We don’t know what we’ll see, and not knowing things can be scary,’ said Mom. ‘But let’s find out together, and the more we know, the less scary things will be.’” The collective, McCarthy reminds us, is key here:“…if we lose each other, we might just get… lost.”

When at last Oktober ventures out on his own timeline and terms, he finds The Wilderness (who McCarthy has given “they/them” pronouns) to be just as big and unfamiliar as he predicted. But with support, the child’s fear has become manageable, and Oktober finds a way to befriend the unknown. “With The Wilderness by his side, Oktober saw all the things he had seen before,” McCarthy writes, “only now he saw them differently.” Nothing about Oktober’s reality has shifted; the Wilderness is still infinite and strange. The only changes are in Oktober’s relationship to that which we can never fully comprehend, and to himself.

If we let it, the natural world offers us endless opportunities to see things anew. So does art. Christo and Jeanne-Claude Wrap the World: The Story of Two Groundbreaking Environmental Artists (G. Neri, ill. Elizabeth Haidle; Candlewick) tells the story of two renegades who spent their lives raising fundamental questions about the possibilities of art: What is it, and for whom? And what are the relationships between art and society, the built environment, and the natural world? The pair was guided by a spirit of open-ended curiosity, and a hunger for touching into unknowing—“They wondered… could they…?”—as opposed to a desire to drive home a particular point. Still, Christo and Jeanne-Claude were provocateurs; “Their projects made people smile or made them mad.” Their work made people feel, and thus “made people see again.”

Most adults need more practice with letting go, and children need modeling and guidance from the grownups in their lives to learn how to do it themselves.

Santiago Saw Things Differently: Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Artist, Doctor, Father of Neuroscience (Christine Iverson ill. Luciano Lozano; MIT Kids Press) tells the story of a person with a similarly restless artistic spirit. As a child, Ramón y Cajal wanted badly to make art, but his father, for whom the pursuit of scientific study trumped that of beauty, forbade it. But the boy persisted, finding ways to pursue his passion in secret. He went on to study medicine, as was his father’s wish, and as a professor of anatomy, was thrust into the 19th-century quest to understand the workings of the human brain.

The scientific community was stumped, unable, with the methods of research prescribed, at the time, by the fields of science and medicine, to make sense of the “tangled forest” of nerve fibers they saw under their microscopes. But Ramón y Cajal didn’t see science and art as separate, and so called upon on the practices he’d been cultivating since childhood, drawing “pictures of the fibers at different stages of growth until his pencil began to unlock patterns,” eventually landing on an understanding of the nervous system as “full of beautifully organized pathways—for thinking reacting, learning and moving.” Ramón y Cajal used art to challenge convention, and by reorienting scientific inquiry in an aesthetic frame, “he had found what he called the ‘mysterious butterflies of the soul,’ those tiny nerve cells that allow us to be part of the world.”

As a parent of a neurodivergent child, I’ve become a student of this chief operating system of human interaction, learning more and more about co-regulation, how our bodies constantly seek ways to tune and calibrate to and with other people. In my family, this beautifully complex system is the story and stuff of our everyday. It’s something the late, legendary illustrator and author Jerry Pinkney—himself a person with a neuro-atypical brain—understood, too. I was raised on Pinkney’s award-winning, boundary-breaking books, of which he’d made over 100 by the time he died in 2021. But before reading his posthumously published autobiography, Just Jerry: How Drawing Shaped My Life (Little, Brown), I knew nothing about his personal story.

Pinkney was born in 1939 in Philadelphia, a city that was then, and remains today, deeply segregated. Discrimination and racial violence were powerful shapers of Pinkney’s childhood world, but they were not the only challenges he faced. From an early age, he struggled mightily to read and write; “When I looked down at the page,” Pinkney wrote in Just Jerry, “the words seemed to be swimming in murky water;” it would be decades before he heard the term dyslexia, at last giving a name to the learning disability that afflicted him.

In an interview he gave towards the end of his life, Pinkney recalled “the pain and exhaustion” of trying to keep up and fit in.” “On the exterior, I was able to draw. I was well liked, dependable, and could make people notice and like me,” he said. “But I was working so hard at being okay.” Unlike Ramón y Cajal’s father, Pinkney’s dad, James, recognized his son’s struggles and put paintbrushes and pencils in Jerry’s hand, encouraging the boy to learn and challenge himself in creative ways. Jerry took to drawing right away; art helped him build his confidence, and gave him a sense of worth and purpose. “I noticed I could do something the other kids couldn’t,” he later recalled. “I had a talent. I drew great satisfaction from making pictures and was acutely aware of how it centered my being, enabling me to focus.”

“If you are lucky enough to be strong and healthy then perhaps you could make the time in your day to be especially kind and understanding.”

Pinkney worked hard to hone his craft, and before long, people began to notice his talent; he sold his first illustration to a regular at the newsstand where he had his first job. And it was there he caught the attention of John Liney, the cartoonist behind the comic strip “Henry.” Pinkney went on to apprentice with Liney, then earned a full ride to the Philadelphia Museum College of Art (now University of the Arts), before launching his career as a graphic artist and illustrator.

And while Just Jerry is unflinching in its attitude towards racism’s ugliness and harm, the book isn’t a tale framed around systemic oppression so much as it is about recognizing, reckoning with, and honoring one’s own particular limitations and gifts. “Drawing carried the weight of my deficiency,” Pinkney said. And while the somewhat dated language of deficiency may rankle, Pinkney’s message—that our struggles often introduce us to our strengths—cuts through.

How many brilliant and winding life paths there are to remind us of this, including that of Gaudi: Architect of the Imagination (Susan B. Katz, ill. Linda Schwalbe; NorthSouth Books; 2022). In Katz and Schwalbe’s rendering, we see the famed architect in his earliest years, when he was afflicted by an illness that kept him from attending school, and often left him alone. Eventually, Gaudi found company and inspiration in the natural world, the influence of which is evident in the iconic structures he later designed.

Long-term illness and its power to isolate and other is also explored in Cloud Babies: Sometimes All We Need to Do is Look Up (Eoin Colfer, ill. Chris Judge). The book seeks to demystify the experience of inpatient hospitalization for children, their families, and the social circles in which they move, and tackles the tricky process of re-integration when treatment has come to an end. “It was easier,” Erin, the young protagonist, initially feels upon being discharged, “to keep her two worlds—hospital and school—apart… Erin felt like she wasn’t fully a part of either group, like she was floating somewhere in between. And it didn’t feel good.”

Colfer makes a rhetorical shift, directly addressing his readers, asking us to acknowledge, and act upon, our beholdenness to and for one another: “If you are lucky enough to be strong and healthy,” he writes, “then perhaps you could make the time in your day to be especially kind and understanding.”

Colfer is writing specifically about “any children in your school who are spending a lot of time in the hospital or who have just returned from a long stay,” but I found myself thinking about people who come back into our, and our children’s, midst after dropping out for all kinds of reasons—the loss of a family member, housing instability, and depression, for example.

I think, too, of those who have been displaced by political forces and who arrive suddenly, strangers in a strange land, like the 20,000 asylum-seekers who enrolled in New York City public schools this past September. “Ask them to tell you about it,” Colfer implores us in a line that choked me up mid-read. “Make sure to tell them that they will always belong. It will make them feel so much happier, and believe it or not, it will make you feel happy, too.”

We know diversity, reciprocity, and symbiosis are not only enriching forces, but keys to survival; all we have to do is look to the study of ecology for proof (For less feelings-y kids, the surprising, symphonic, and sometimes “ewwww” inducing world of microbial life—explored, this year, in Meet My Micropets [ill. Tiffany Everett, Little, Brown], by Molly Bloom, Marc Sanchez, and Sanden Totten, the team behind the “Brains On” podcast, and Unseen Jungle: The Microbes That Secretly Control Our World [Eleanor Spicer Rice, ill. Rob Wilson; MIT Kids Press]—can provide a pathway into understanding these concepts). And yet, on both individual and societal levels, we still struggle to fully accept and integrate these truths.

I’ve found it particularly helpful to read and think alongside Andrew Solomon, via his Far From the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity, Sara Hendren, by way of her book What Can a Body Do: How We Meet the Built World, and the poet and activist Kay Ulanday Barrett. Each writer comes at their work from a different vantage point; Solomon is a writer, lecturer on psychology, and LGBTQ activist who identifies as gay; Hendren trained as a visual artist, is the parent of a child with Downs syndrome, and teaches disability-informed design; and Barrett, who identifies as “disabled Filipnx-amerikan transgender queer,” writes about, and organizes towards, “disabled and trans brown wobbly resilience.” All three, though, make a strong case for leaning into the learning that happens when relationships of love and care are formed across boundaries of identity and ability.

I love the phrase “wobbly resilience” for the way it tries to acclimate us to the idea that, in order to be both sturdier and more flexible at once, we have to grow used to constantly accommodating, and recalibrating to, our ever-shifting reality. This is an area in which folks who identify as differently- and dis-abled are, by virtue of our ableist culture, particularly well-experienced, and one of many realms in which those who see themselves as falling within the “norm” stand to learn a great deal from those in the so-called margins. That doesn’t mean, though, that the onus is on those in the disability community to teach those outside of it. Quite the opposite.

We are reminded of this in What Happened to You? (James Catchpole, ill. Karen George; Little, Brown). Joe is a child with one leg who, on the playground one day, is asked by another kid “What happened to you?” Joe is both accustomed to, and exhausted, by such questions about his body, and we see him try to wriggle out from having to explain the fact of his physical form. We also see him creatively and thoughtfully respond rather than react when, in turn, he asks his peers, “What do you think” and ask, at last, after a gaggle of kids joins in to conjure outlandish possibilities for how a person might lose a limb, “Do you still need to know?” Because Joe just is a kid like all the rest, who just wants to be part of the mix, and lose himself in raucous, joyful play.

What Happened to You? provides a useful framework for talking with kids about relating to peoples physical differences and our curiosity about variations in bodies. It’s a tricky line to walk; we want our children to ask questions, to seek to understand and learn across differences, but we also need to insist they practice respect for people’s privacy and dignity.

I discourage my kids from commenting on people’s bodies as a general rule, and try to draw their attention away from appearances in general. What else can we perceive about a person, I ask them, beyond what meets the eye? As we all know, seeing can be deceiving, and outward appearances are often poor representatives of someone’s true self. My child who moves through the world as trans understands this better than I likely ever will, and is my foremost teacher on this front.

Barrett, Solomon, Hendren, and indeed, all of the authors on this list, beckon us to examine, again and again, our notion of a “good” life and bust through the categories we, ourselves, have created and reified that continue to keep us apart. These writers help us recognize that we are, inextricably, bound, united by what Hendren calls our “needfulness.” Accepting responsibility for one another is not to resign ourselves to a burden of sacrifice so much as it is a means of releasing the false and harmful construct of individualism. As the poet Gwendolyn Brooks wrote, we are each other’s / business: / we are each other’s / magnitude and bond. This throughline is as spiritual in nature as it is political in its implications.

We have to hold and to “manage grief and life” at once, writes Melvina Noel in Chef Edna: Queen of Southern Cooking, Edna Lewis (ill. Cozbi A. Cabrera, Cameron Kids), both for and with our children. Because things aren’t just going to settle down on their own, and they aren’t getting any easier. There is so much real loss, so much to mourn. As Edna Lewis, herself, wrote, “The world has changed. We are now faced with picking up the pieces and trying to put them into shape.” Make no mistake, this is no abstract philosophy. It is our daily task.

Sara B. Franklin

Sara B. Franklin is a writer, teacher, and oral historian. She received a 2020–2021 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Public Scholars grant for her research on Judith Jones, and teaches courses on food, writing, embodied culture, and oral history at NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study. She is the author of The Editor, the editor of Edna Lewis, and coauthor of The Phoenicia Diner Cookbook. She holds a PhD in Food Studies from NYU and studied documentary storytelling at both the Duke Center for Documentary Studies and the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies. She lives with her children in Kingston, New York.