There is nothing so nice as being whisked somewhere in a car, very fast.

My father was to the motor born. He drove for pleasure when he was calm and drove for relief when he was enraged, and drove for the sake of driving. He’d take anyone anywhere; all you had to was ask. “Come,” he’d beckon when I was a child, “let’s go for a ride.” I hopped in and we were off. No seat belts to fuss with back then.

He drove rashly and aggressively but with perfect control, and I always felt quite safe as well as excited to be his passenger. Excited because, beyond the eccentricities of his moves—cutting across lanes of traffic to make a turn, or driving in lanes blocked off for construction—we were playing the game of life: driving was triumphing over others, getting there not only quicker, but with panache. His driving was a performance: he wanted to steal the show. Buses, other cars, pedestrians, even street furniture like lampposts or mailboxes were impediments to his progress. He would keep up a running commentary on his fellow drivers, a commentary rich with derision. Anything moving less nimbly than we seemed too risible to exist, never mind occupy the road. He had no major accidents and just a few minor ones, David-and-Goliath fender benders, born of hubris.

This all held me spellbound. I assumed driving skill was an inherited trait and I would become the same kind of bold, virtuoso driver as my father. This, alas, did not happen. Quite the contrary. Perhaps because unlike my brother and sister, I didn’t have the benefit of my father’s instruction but learned at a driving school in Boston, a city known for its fearsome traffic.

My brother was born with driving in his DNA: from the age of two he could identify the make and name of any car pictured in a glossy magazine, and grew up to be as gifted at the wheel as our father, though less wedded to the performance aspect. My sister learned to drive under my father’s harrowing tutelage. He would have her maneuver through heavily congested lower Manhattan while he dashed in and out of the car on business errands or for quick phone calls. “Drive around the block if you see a police car,” and if she demurred, “What could happen?” he would say. She turned out a good driver too, an easygoing, reliable driver, I don’t know how.

I heard a neighbor casually remark that whenever you step into a car you’re taking your life in your hands. Certain words stick in the mind, or the mind clings to them. This bit of warped wisdom wasn’t even true, or true only in the sense that any venture out of bed might be life-threatening. But I never forgot it. As a driver, I was alarmed by the other cars whizzing past. I was less afraid of being killed than of killing someone. Failing that, I would do something clumsy and gauche and be mocked for it, as my father had mocked other drivers: I thoughtlessly assumed everyone must harbor the same antagonism as he did. My fear was a species of social anxiety, the anxiety of an inexperienced person at a formal event, like meeting royalty, afraid of committing a ghastly blunder.

In their presence I was unquestionably a grown-up, entitled to the driver’s seat.The road had its grown-up male rites, the ignorance of which could bring lasting shame: how to merge, how to get gas, how to rent a car, and Heaven forbid, how to fix a flat tire. What’s a girl like me doing in charge of this powerful machine about whose workings I understood nothing? Even the radio was a challenge, never mind the more intricate parts. I dreaded a minor accident more than a major one.

At the same time I felt the opposite, a dread of my own power: I sensed that I could be a bold driver. My father’s driving genes, lurking within, might suddenly assert themselves. I could be a master of the road. I yearned for this and dreaded it. The dread was strongest when I was alone. With passengers aboard I was calm: surely I wouldn’t risk anyone’s life by letting those anarchic genes run rampant. I was most at ease driving with my children—I would never endanger them. In their presence I was unquestionably a grown-up, entitled to the driver’s seat.

The first car of my adult life was a red Renault Dauphine my husband and I named Dauphie. A babyish name; we were hardly more than babies ourselves, recently married at an absurdly young age, going to graduate school. Joining us in our quest for adventure, Dauphie traveled across the Atlantic to Italy in the bottom of a ship called the Leonardo da Vinci, probably in more comfortable circumstances than ours in a tiny room up above. It was a long trip during which we played deck tennis and ate more meals each day than one usually does. We were relieved to dock at Naples and begin the perilous and splendid drive along the Amalfi coast to our destination, Rome. We drove Dauphie all around Rome and to many small cities in Italy and grew fond of her.

But her behavior changed when we returned to the States. Parts began falling off, such as an inner door handle, the rear-view and side-view mirrors, which we re-attached with duct tape. The worst symptom Dauphie developed on returning home was a refusal to move in reverse. This made parking difficult on the hilly streets of Boston’s Beacon Hill, where we had found our first real jobs. When we stopped to pay a toll and overshot the booth; whoever was driving had to step out of the car to reach the toll-taker’s outstretched hand. We lost our affection for Dauphie. She would have to be replaced.

But we couldn’t afford a new car or even a used one, and Dauphie, with her idiosyncrasies and decorative patches of duct tape would not be worth much in a trade. Fortunately my mother was ready to get rid of her car so she offered it to us.

My mother learned to drive in her fifties, when she and my father moved from Brooklyn to the nearby suburbs, where you must drive in order to have a life. Given their very different temperaments, she took lessons instead of being taught by my father. She was plucky and confident, a confidence quite misplaced, since her driving was the stuff of farce. For a good while into her driving career she believed the rearview mirror was for powdering her nose. When first driving on the Palisades Parkway she was astonished at the friendliness of her new neighbors—all the other drivers were waving at her. Finally it dawned on her that she was going north in the southbound lanes.

Once a week she came into Manhattan, our next home, to take care of my small children so I could get to my part-time job. She said, “I always thought a woman should stay home with her children, but in your case I see you can’t. So I’m coming.” On one occasion she called to explain her lateness: she’d inexplicably missed the proper downtown exit and had driven from one river of Manhattan to the other, ending up in Queens because she couldn’t find a place to make a left turn. None of this daunted her. She had an enviable devil-may-care attitude to driving, perhaps from decades of being my father’s passenger.

My mother’s hand-me-down was a shiny gold-colored Mercury and much larger than we were accustomed to. We accepted the old car gratefully and called it Sarah, in honor of my mother. The car was similar to her in its shininess and boldness; it was oversized like my mother, and like her it behaved generously to us. Friends teased us for having such a large, flamboyant car—it was the era of rebellion in the sixties and we scorned symbols of middle-class materialism—but nonetheless we loved Sarah because she was willing and cooperative and didn’t exhibit any of the neurotic and disabling symptoms of her more exotic predecessor.

I drove Sarah when it was unavoidable. I was assured that were I to drive regularly I would eventually feel at ease. Yet the idea of getting behind the wheel filled me with dread. I tried to adopt my father’s outlook: What could happen? Plenty. The steering wheel could lock in place and the car could run amok. The gas pedal could get stuck, or maybe the brake: one way or another, I would be unable to stop. Should I drive until I ran out of gas? That might take me to Canada or beyond.

Despite all of this nonsense I did like the feeling of unlocking the car and climbing in, breezy and grown up, looking like any ordinary driver, not someone who was taking her life in her hands. But the cloud of dread shadowed me. I planned each trip in detail, reviewing every turn, every traffic light, every lane change. Once I started the engine, the cloud would disperse. What a relief to be driving and not anticipating driving! Anticipation is almost always worse than whatever is anticipated. In fact I handled the car well enough; I liked to drive fast, and at times I even felt the elation of power, of controlling this menacing and mysterious machine. I even got in the habit of cursing other drivers, as my father did, but more for the ritual, without any passionate conviction.

I don’t remember Sarah’s end, but I imagine she succumbed to the natural infirmities of age, like her namesake. As it happened, around the time Sarah expired, my sister and brother-in-law were about to trade in their old car and they offered it to us instead.

This car was also large but not as large as Sarah, and it was the opposite of shiny—a sort of nondescript gray-green color—and it was generally self-effacing and dull in every way. Self-effacing in the sense that if you forgot where you parked it in a large lot, you might pass by several times before you recognized it. Because of its flagrant dullness we called the car Herman, and before long came to feel affection for him.

When we moved to New York, though, Herman was stolen. It was an era of car thefts in our neighborhood. Some thieves didn’t even bother with subterfuge. Our niece from Long Island had come to live with us while she attended college. Her first night in our apartment, rather late, I found her staring out the window. When I inquired, she said she saw someone use tools to open the door of a car parked just below our window and after some effort, got it started and drove off. I explained that she had witnessed a car theft and must call the police should it happen again. Although everyone knew that by the time the police arrived any stolen car would be far away.

We were sorry to lose Herman, and to lose him in such a sordid way—an unworthy end to a respectable career. But one must move on. At this point we could afford to buy our own car, and we chose a red Toyota station wagon. Since our children were now old enough to take part in the naming of the car, its christening, as it were, we conferred and finally agreed on Naomi.

We lived with Naomi for many years and she made many trips. She was a good-natured car but whimsical. Like the original Dauphie, parts of her had a tendency to fall off. Also, she was accident prone. Not serious accidents; rather, she was the victim of more aggressive vehicles. Often we would find her injured. She had dents and scrapes all over, like a boy who’s been in a fight. We covered her injuries with duct tape, the automotive Band-aid, and in time she had so many stripes that she resembled a racing car. Which was ironic, because one of her whimsical traits was a refusal to accelerate quickly.

There came a time when Naomi was too debilitated to drive anymore. Our children were nearly grown and could navigate the city on their own. Our parents were gone so there was no need to visit them. The only thing was, how to get rid of her. Like Dauphie, she was too moribund to be traded in. My husband worked frequently in New Jersey and he decided to abandon her there, heartless as that seemed after her years of service. One night he removed everything that might serve as identification, left her in a parking lot in a Jersey town just over the George Washington Bridge, and took a bus home. We were free of her! No more car to move, no more rolls of duct tape to buy. Imagine our surprise when a couple of weeks later we got a phone call from a police officer in New Jersey. He announced that he had good news. I’m happy to tell you, sir, that we’ve found your car, he said. You can come and pick it up. He reasonably assumed it had been stolen. Apparently an envelope with Harry’s name and address had been found under one of the seats.

It is illegal to abandon cars. Harry tried to match the officer’s enthusiasm. Oh, thank you so much, he said. I’ll come right over.

So we had Naomi back. We drove her around for a while longer, until a man working in a nearby service station said he could fix her up and use her. He offered 50 dollars, a generous sum, considering her condition. Though she might have been sporting 50 dollars’ worth of duct tape.

I was relieved, thinking I need never drive again. In that mood of relief, I spoke to my older sister about my driving anxieties. I thought she might understand, having grown up with and been taught to drive by our father. She was sympathetic, but dismissed my father’s approach: “He was a madman on the road. You can’t let his driving influence you.” She said I had the right to drive in whatever manner felt comfortable. The car was simply a means of getting somewhere. She had no contempt for other drivers; she had no interest at all in other drivers. The road was a community in which we all pursued our destination at our own pace. Naturally we observed the social contract, for our common good. But essentially we were following our individual paths. A new slant on the game of life on the road.

You might think that after this great yet banal revelation, I would drive with ease. But that did not happen. To my father, and to me when I was his passenger, the road was not a cooperative community but the state of nature. And the allure of that state was powerful. To move with such arrogance and abandonment, such predatory skill! But I didn’t yield to the lure, and surely it was better so.

Better because we were not yet finished with cars. We were so used to the freedom of having a car around, like a family member… We bought a used car, so nondescript that I barely remember it. We were past fifty now and our children were grown, with lives of their own. Our childish habit of naming and personifying cars was over, a sobering sign of maturity. When I drove this nameless car, I tried to remember my sister’s wise advice about the road of life. I muttered curses when a nearby driver did something clumsy or inept. Aside from that harmless indulgence, I observed the social contract, but I longed to be in a state of nature. The tension was exciting. Anything might happen. Elation, power, and dread swirled in my every cell.

Our daughter and son-in-law were in the habit of borrowing this unloved car for week end trips, and one Sunday they called to say it had been in an accident on the way home. Nothing serious; they were unhurt. Our son-in-law, an experienced driver from Minnesota, where kids often learn to drive around twelve years old, had been going 15 miles an hour on an exit ramp when our car and another attempted to occupy the same space. The car was only slightly banged up, but the insurance company pronounced it dead and refused any compensation.

I didn’t care anything about the car; I was ready to live without it. My husband wasn’t too upset either: he had recently announced that after this car died he never wanted to own another car again. Enough! What we cared about was our daughter, who was in the early stages of pregnancy. But we were assured that the impact was not enough to shake anything up.

Several months later our granddaughter was born in perfect condition, and while we never had another car again we had a new member of our family who could do so many wonderful things a car could not, and instead of causing dread brought pure delight.

__________________________________

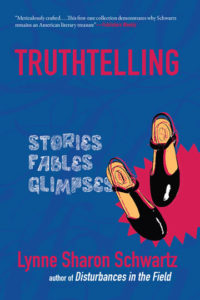

Truthtelling by Lynne Sharon Schwartz is available via Delphinium Books.