Late September arrives and for a week the weather is perfect, sunny and cool. Each morning the leaves are brighter, turning the rolling mountains around Norumbega into a mess of color. Campus looks like it did in the brochure I obsessed over as I filled out my Browick application—students in sweaters, the lawns a brilliant green, golden hour setting white clapboard aglow. I should enjoy it, but instead the weather makes me restless, panicked. After classes I’m unable to settle down, moving from the library to the Gould common area to my dorm room and back to the library. Everywhere makes me antsy to be someplace else.

One afternoon I loop through campus three times, unsatisfied with all the places I try—the library too dark, my messy dorm room too depressing, everywhere else crowded with people studying in groups that only highlight me being alone, always alone—before I force myself to stop at the grassy slope behind the humanities building. Calm down, breathe.

I lean against the solitary maple tree that my eyes drift to during English class and touch the back of my hand to my hot cheeks. I’m so worked up I’m sweating, and it’s only fifty degrees.

This is fine, I think. Just work here and calm down.

I sit with my back against the tree and reach into my backpack, feeling past my geometry textbook to my spiral notebook, thinking I’ll feel better if I work on a poem first, but when I open to my latest one, a couple of stanzas about a girl trapped on an island who calls sailors to shore, I read over the lines and realize they’re bad—clumsy, disjointed, practically incoherent. And I thought these lines were good. How did I think they were good? They’re blatantly bad. Probably all my poems are bad. I curl into myself and grind the heels of my hands against my eyelids until I hear footsteps approach, crunching leaves and cracking twigs. I look up and a towering silhouette blocks out the sun.

How did I think they were good? They’re blatantly bad. Probably all my poems are bad. I curl into myself and grind the heels of my hands against my eyelids until I hear footsteps approach, crunching leaves and cracking twigs.

“Hello there,” it says.

I shield my eyes—Mr. Strane. His expression changes when he notices my face, my red-rimmed eyes. “You’re upset,” he says.

Gazing up at him, I nod. There doesn’t seem to be any use in lying.

“Would you rather be left alone?” he asks.

I hesitate, then shake my head no.

He lowers himself to the ground beside me, leaving a few feet between us. His long legs are stretched out, the outline of his knees visible beneath his trousers. He keeps his eyes on me, watches as I wipe my eyes.

“I didn’t mean to impose. I spied you from the window there, thought I’d say hello.” He points behind us, to the humanities building. “Can I ask what’s upsetting you?”

I take a breath, try to work out the words, but after a moment I shake my head. “It’s too big to explain,” I say. Because it’s about more than my poem being bad, or that I can’t pick a study spot without exhausting myself. It’s a darker feeling, a fear of there being something wrong with me that I won’t ever be able to fix.

I expect Mr. Strane to let it go at that. Instead, he waits the same way he’d wait in class for a response to a tough question. Of course it seems too big to explain, Vanessa. That’s how hard questions are meant to make you feel.

Taking a breath, I say, “This time of year just makes me feel nuts. Like I’m running out of time or something. Like I’m wasting my life.”

Mr. Strane blinks. I can tell this isn’t what he expected me to say. “Wasting your life,” he echoes.

“I know that doesn’t make sense.”

“No, it does. It makes perfect sense.” He leans back on his hands, tilts his head. “You know, if you were my age, I’d say it sounds like you’re in the beginning of a midlife crisis.”

He smiles and, without meaning to, my face mirrors him. He grins, I grin.

“It looked like you were writing,” he says. “Were you getting good work done?”

I lift my shoulders, unsure if I want to call my writing good. It seems boastful, not for me to say.

“Would you show me what you’ve written?”

“No way.” I clutch my notebook in my hands, hold it closer to my chest, and in his eyes I see a flash of alarm, like my sudden movement has scared him. I steady myself and add, “It’s just not finished.”

“Is writing ever really finished?”

That feels like a trick question. I think for a moment, then say, “Some writing can be more finished than other writing.”

He smiles; he likes that. “Do you have something more finished you can show me?”

I loosen my grip and open the notebook’s front cover. It’s full of mostly half-finished poems, lines scrawled out and rewritten. I thumb through recent pages to find the one I’ve been working on for a couple weeks. It isn’t finished, but it isn’t terrible. I hand him the notebook, hoping he won’t notice the doodles in the margins, the flowering vine crawling along the spine.

He holds the notebook carefully in both hands, and just seeing that, my notebook in his hands, sends a jolt through me. No one else has ever touched my notebook before, let alone read anything in it. At the end of the poem, he says, “Huh.” I wait for a clearer reaction, for him to let me know if he thinks it’s good or not, but he only says, “I’m going to read it again.”

When he finally looks up and says, “Vanessa, this is lovely,” I exhale so loudly, I laugh.

“How long did you work on this?” he asks. Thinking it’s more impressive to come across as an instantaneous genius, I shrug out a lie.

“Not long.”

“You said you write often.” He hands the notebook back to me.

“Every day, usually.”

“It shows. You’re very good. I say that as a reader, not a teacher.”

I’m so delighted, I laugh again, and Mr. Strane smiles his tender-condescending smile. “Is that funny?” he asks.

“No, that’s the nicest thing anyone has ever said about my writing.”

“You’re kidding. That’s nothing. I could say much nicer things.”

“It’s just I never really let anyone read my . . .” I almost say stuff but instead try out the word he used. “My work.”

A silence settles between us. He leans back on his hands and studies the view: the picturesque downtown, distant river, and rolling hills. I look back to my notebook, eyes turned down at its pages but seeing nothing. I’m too aware of his body next to mine, his sloping torso and stomach straining against his shirt, long legs crossed at the ankle, how one of his pant legs has bunched up, revealing a half inch of skin above his hiking boot. Worried he might get up and leave, I try to think of something to say to keep him here, but before I can, he plucks a fallen red maple leaf off the ground, spins it by its stem, considers it for a moment, and then holds it up to my face.

I’m too aware of his body next to mine, his sloping torso and stomach straining against his shirt, long legs crossed at the ankle, how one of his pant legs has bunched up, revealing a half inch of skin above his hiking boot.

“Look at that,” he says. “It matches your hair perfectly.”

I freeze, feel my mouth fall open. He holds the maple leaf there a beat longer, its points brushing against my hair. Then, shaking his head a little, he drops his hand and the leaf falls to the ground. He stands—again blocking out the sun—wipes his hands on his thighs, and walks back to the humanities building without saying goodbye.

When he disappears, a mania seizes me, a need to flee. I snap my notebook shut, grab my backpack, and start off toward the dorm, but then think better and double back to scan the ground for the exact leaf he held up to my hair. Once it’s safe, tucked between the pages of my notebook, I move across campus as though airborne, barely making contact with the earth between strides. It isn’t until I’m back in my room that I remember he said he saw me from his window, and I squeeze my eyes shut against the thought of him back in the classroom, watching me search for the leaf.

__________________________________

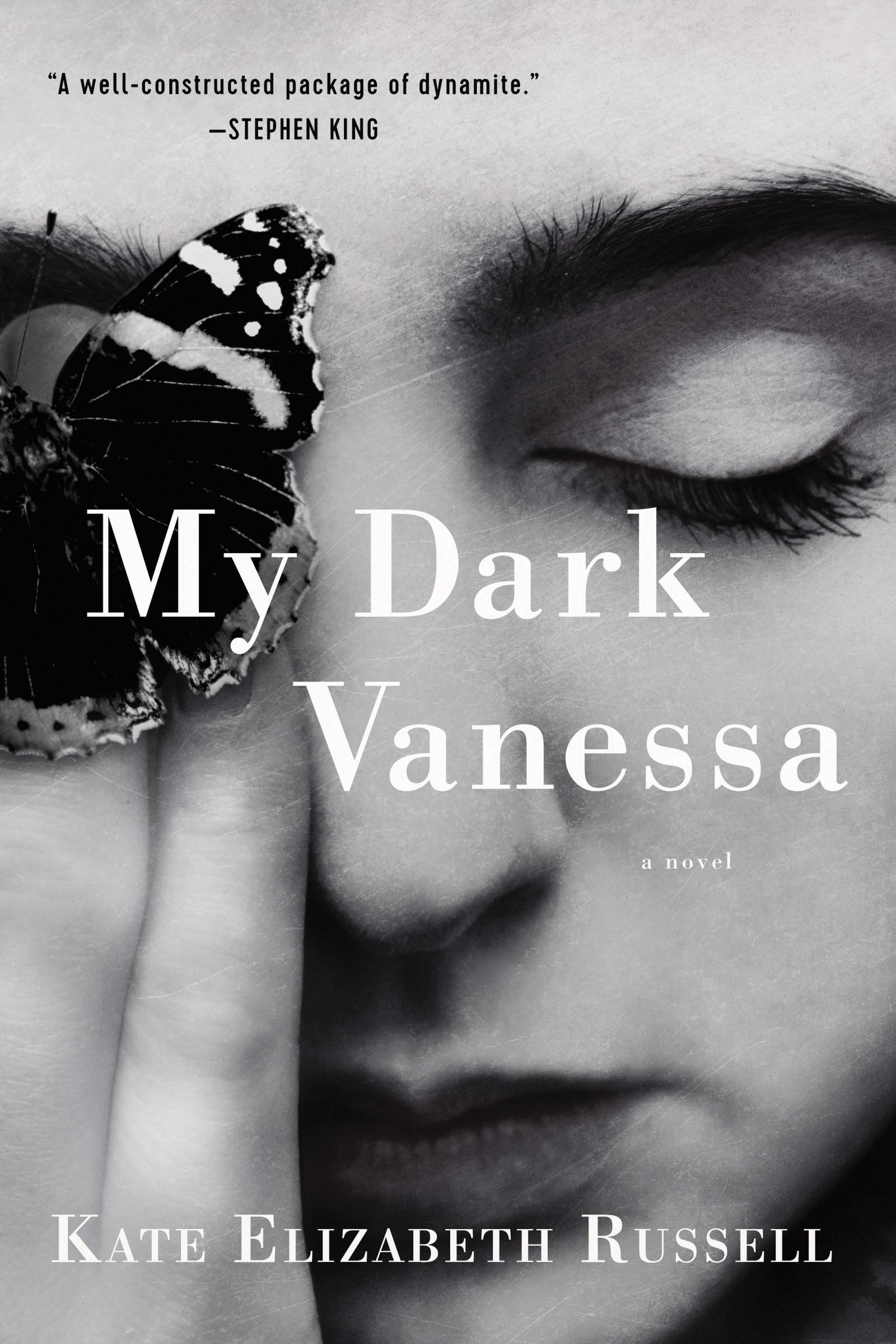

From My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell. Copyright (c) 2020 by Kate Elizabeth Russell. Reprinted courtesy of William Morrow, a division of HarperCollins Publishers.