My Cyborg Future: Alice Wong on Prophetic High School Poetry and Processing Pain

“Joints contracted, muscles atrophied, sinews snipped and stretched to the brink. Great art comes at a great price.”

“All responses to the world take place within our bodies.”

–Gloria Anzaldúa

*

In putting together my book and making selections from past work, I desperately wanted to include a poem from my high school literary magazine to give readers a glimpse of my inner emo goth self. I emailed a librarian at Carmel High School in 2020, asking if they kept any digital or hard copies of the student literary magazine The Prerogative from 1991 or 1992. Unfortunately this was too far back in ancient history (yikes), and reaching out to a teacher who was at C.H.S. during those years didn’t produce any results, either. Womp, womp.

However, three lines from the poem remained etched in my memory. Here are the words from my fractured, untitled, morbid poem:

I have a tube that feeds me

I have a tube that breathes me

Beeeeeep!

Referring to the flatline from a heart monitor, I ended the poem with death. How terribly melancholic and full of adolescent ennui. I cringe now at the thought of my hair, fashion choices, and writing at the time but truly marvel at the prescience of this poem as someone who has since talked and written about disabled people as cyborgs and oracles.

There were actually two poems published in The Prerogative, and they both almost didn’t make it in. The second poem was about bitterness and candy; no specific lines or other details come to mind except the word sucking. Like I said, cringey. A student who worked on it told me when I saw her that year at Steak ’n Shake (an excellent place for thin smash burgers and super-thin fries) that the editor thought my content was “too dark.” Luckily this student and others who worked on the magazine inserted it back in the final proofs. Thank you, fellow creative comrades! Nice to know I remain on brand to this day.

The more I think about the first poem foretelling my cyborg future, I understand it now to be rooted in a critical period of my evolutionary embodiment. I already was a cyborg teenager before acquiring the consciousness of being one.

By the time I was fourteen I had severe scoliosis, which put pressure on my lungs and shifted additional weight of my torso to the right side. I leaned in before white feminists made it a thing. When I could walk as a young child, I was wobbly and moved in slow, tentative movements. Using a wheelchair, I was still unbalanced, with this progressive curvature of the spine due to my back muscles unable to support my upper body. A back brace was just a temporary stopgap, providing better posture in exchange for sweaty, miserable discomfort.

There were other signs of how the curve in my spine showed up in the rest of my body. When sitting and looking at my thighs, I could compare my unevenly aligned kneecaps. Time and biology shaped my body into a gnarled, knotty driftwood sculpture, marked by the elements and forces of nature into an abstract masterpiece. Joints contracted, muscles atrophied, sinews snipped and stretched to the brink. Great art comes at a great price.

Time and biology shaped my body into a gnarled, knotty driftwood sculpture, marked by the elements and forces of nature into an abstract masterpiece.

Doctors advised me to get spinal fusion surgery when I was around twelve, but I was too freaked out by the thought of it because it was a serious-ass procedure. By eighth grade my parents told me I was near the final window for this surgery, which could improve my breathing and alleviate the deep fatigue I experienced every day. I relented—with no idea how it would turn me into a cyborg inside out.

Riley Hospital for Children in downtown Indianapolis was a beautiful space in the late 1980s and ’90s. My pediatric muscular dystrophy clinic was at Riley, and I had my surgery there as well. Huge stuffed animals were perched on every floor that could be seen from the main atrium. Glass elevators in the center of the hospital made kids feel like they were at a hotel instead of a place for scary medical appointments. There were automatic doors and accessible spaces. Color everywhere. Soft-serve ice cream in the cafeteria! For all the unpleasantness that can come from the medical-industrial complex, hospitals, especially children’s hospitals, were a place where I felt like I belonged in a very weird way. No one batted an eye at a wheelchair user or someone who looked different or who needed help eating or using the bathroom.

I spent six weeks in the hospital in the middle of a scorching summer, mostly in the intensive care unit, which was atypical. My delaying the surgery, which involved the insertion and fusion of Luque rods and wires to each affected segment of vertebrae in the spine, undoubtedly increased the complications and the recovery period. According to my parents, the surgery took much longer than expected. They figured it must have been touch-and-go but don’t remember the specifics.

Being under anesthesia for a prolonged period of time with my neuromuscular disability, I was on a mechanical ventilator and went through a succession of extubation and reintubation post-surgery when I could not breathe without assistance. Eventually, pediatric pulmonologists took over my case and slowly weaned me off the ventilator rather than a drastic withdrawal, which could cause a crash in blood oxygen levels. Shout-out to Dr. Kling, my orthopedic surgeon; Dr. Eigen, my pulmonologist, who actually had a post-surgery critical care plan that worked; and the amazing I.C.U. nurses who cared for me and performed the bulk of the labor during that time.

I had to adapt or die. There was metal inside the core frame of my spine and additional attachments to my external humanoid shell at age fourteen.

To say this was a period of incredible pain is an understatement. Fluid would build up in my lungs from being on mechanical ventilation. I couldn’t communicate, but I buzzed for a nurse whenever I heard the crackles and gurgles grow louder and louder. Through eye contact and nods, the nurse knew what I needed and would trickle some saline down my breathing tube to break up the secretions, then thread a narrow cannula into my lungs and start suctioning. I could feel the cannula poking around as the nurse vacuumed my trachea.

Having clear lungs felt wonderful afterward, but repeated suctioning caused some minor bleeding, and I saw spots of red in the sucked-up secretions once in a while. I had a gastric tube inserted through my nose for nutrition when it was clear my complications would require weeks of care. I had to swallow the tube as a resident stuck it forcefully up my nose so that it would go down into my stomach. I experienced internal bleeding and had to be rushed back to the operating room for examination.

The air-conditioning didn’t work for a few days on my I.C.U. floor, and the humid Midwestern heat made my small room feel even more oppressive on top of having a body lit on fire with a fresh, long incision along my back trying to heal. And I still got my period and, for shits and giggles, got a yeast infection due to all the medications I was on! Needless to say, I had a lot of things inserted into every orifice. These were the sights, smells, sensations, and sounds from my summer vacation, since my parents didn’t want me to miss any school from the hospital stay (of course). Good times.

My sisters, Emily and Grace, had to fend for themselves as my parents took turns staying with me, driving from our home in suburban Carmel to downtown Indianapolis. Families from our church would bring food and take them out, but for the most part they spent their summer days camped out on the pull-out couch in the living room watching T.V. and being good little bunnies, like Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail from Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Emily and Grace didn’t have a great summer, either.

Mom and Dad had it rough, but they never complained or showed worry. They were 100 percent there for me and that was their way. Mom spent a majority of the time by my side in a reclining chair for the brief periods she could rest, helping the nurses who came in and out of my room at all hours of the day. Mom was the first to notice I was disoriented when a respiratory therapist left my oxygen on too high or low. The privilege of having a constant parental presence sent a clear message to the hospital staff: “We are watching. We are here.” I am sure this contributed to the quality of my care.

Once in a while, Mom would try to sleep in the parents’ lounge, but her wallet was stolen (along with other parents’ wallets) in the middle of the night. I hope that person really needed the money, because who could be so cruel as to steal from exhausted, sleep-deprived parents of sick kids? I mean, really?! The shit was too real for all of us that summer.

I do not regret waiting to have the surgery until it was almost too late. My parents respected the autonomy I had over my body, knowing the risks it might bring.

Near the end of my hospital stay, as I prepared to go home, I found out that almost dying from this surgery and its complications had weakened my diaphragm to a point where I required respiratory therapy at home with intermittent positive pressure breathing (I.P.P.B.) treatments that temporarily expanded the lungs and provided medication such as albuterol through a nebulizer. When the doctor said this therapy was indefinite, not a temporary part of my recovery, I burst into tears because it was another major change in my disabled life, after I stopped walking and started using a wheelchair full-time. I also had to wear a nasal cannula with a low level of oxygen every night. This was before I started using a BiPap at eighteen years old, after another cyborg turning point brought about by respiratory failure.

I had to adapt or die. There was metal inside the core frame of my spine and additional attachments to my external humanoid shell at age fourteen. I had to figure shit out. And there would be more difficult shit to figure out in my twenties, thirties, and forties, as the driftwood became more weathered through pressure, fire, and rain, with craggy and bony bits damaged and torn away.

I do not regret waiting to have the surgery until it was almost too late. My parents respected the autonomy I had over my body, knowing the risks it might bring. What I did not realize was how there wouldn’t be an end date for recovery, that it would be only one event in a cycle of writing and rewriting this operating system, each reboot preserving and accumulating memories. The long scar lining my back is less sensitive and spiky to the touch when it rains, a pain echo from the past. The lower left corner of my back where drainage tubes were left in after surgery remains numb and simultaneously itchy as hell because of nerve damage. My right inner wrist has two keloid scars that have grown over time from arterial lines placed to provide a convenient spigot instead of multiple blood draws during hospitalization. I was in the I.C.U. so long, one had to be replaced, and on both occasions, I was stabbed multiple times by residents attempting to insert the line into the radial artery, adjacent to the radial nerve. These two reddish-brown scars in particular are raised and have spread as I age.

Even now, if I accidentally scratch or brush my wrist against a surface, I flinch at the overwhelming painful sensations. I look at the surface of the scar with its dry, cracked skin and cannot resist the impulse to pick it off, as if to remind myself of the past. Each new sensory input is another data point to be analyzed on what a body can endure and has endured. I may be an old cyborg model, but my programming is extremely sophisticated.

The poems I wrote in high school were my first attempts at verbalizing and processing the violence my body experienced only a few years earlier. It was telegraphing messages of what’s to come and the need to listen carefully. Nora Shen, a family friend, was recently cleaning out some old boxes and sent me two issues of The Fine Print, a college literary magazine from my years at Indiana University; she was unaware of this memoir, nor that I was in the middle of writing this very essay. Boom! Somehow the universe heard my cry and delivered more angsty crip technoscience poetry. The connections have always been and continue to be there. Even bad poetry has the power of prophecy.

*

Hooked Up Online (1995)

I have a tube that pees me

I have a tube that feeds me

I have a tube that breathes me

fluids dripping while others

swim in a raging torrent

urgently delivering goods

importing necessities

exporting wastes along these

worn down roads

no orifice left

un plugged

all functions hygienically

maintained

plastic wrapping

hermetically sealed

plastic straws

stick

rub

itch

the skin

sweat and dirt builds up around

the point of insertion

with a mound of ragged stained bandages

gauze and tape securing

the connections down

despite the incessant mosquito bite itch

tube upon tube,

intricate byways that laugh at nature

interconnecting, overlapping

the interstate of my body

*

Time Restrained (1996)

a fiberglass corset

a hull with

foam padding

the brace was constructed to slow the curvature of the bones

pressure on the structure

weakens the stature

like the one for that lady in new york

hers was made of iron and steel

to hold up her bulk

even she had problems with posture

old men surrounding her in

her underwear

applying plaster and

creating a mold of a girl aged nine

now you won’t waddle like a duck

they said

when the orthotist presented her with this

new appliance

now you’ll need to wear this every day

so it can hold you up

and give you balance

it’ll be part of your normal routine in no time

in no time

encased in this insulated shell

is a soft mass of flesh

atrophied and decaying with

pockets of larvae wriggling for space

yearning to breathe

as the girl goes to school and sits

under the hot sun during recess

_____________________________

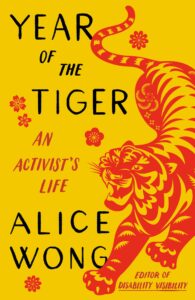

From Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life by Alice Wong. Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Alice Wong.

Alice Wong

Alice Wong is a disabled activist, media maker, and research consultant based in San Francisco, California. She is the founder and director of the Disability Visibility Project, an online community dedicated to creating, sharing, and amplifying disability media and culture. Alice is also the host and co-producer of the Disability Visibility podcast and co-partner in a number of collaborations such as #CripTheVote and Access Is Love. From 2013 to 2015, Alice served as a member of the National Council on Disability, an appointment by President Barack Obama. You can follow her on Twitter: @SFdirewolf. For more: disabilityvisibilityproject.com.