Must Sex Always Mean Death When it Comes to Horror Movies?

Tyler Malone on Carnal (Lack of) Knowledge in Scary Cinema

I.

The Battle of the Sexlessness

We live in ostensibly sexless times, though we remain undeniably sex-soaked beings. Even as today’s adolescents are more likely to express their sexual identity publicly and as the general acceptance of identities that don’t neatly fit into society’s heteronormative structures has greatly increased, Gen Z is having less sex than previous generations. And not just them.

In America at least, if not the world, research shows that people of all ages are having less sex. Permissiveness has not increased our erotic entanglements, but somehow diminished them. Yet desire does not merely dissipate, for we are nothing without our libidinal investments. Eros can’t be gotten rid of because “sex is the essence of existence,” at least according to director Paul Verhoeven, whose films Basic Instinct, Showgirls, Elle, and Benedetta force us to contend with that very fact.

Our movies track this societal stumble toward sexlessness. Actors and actresses may appear closer to perfect physical specimens than ever before—thanks to insane diets, workout regimens, Botox, plastic surgery, and, of course, CGI—but the films they star in seem sterilized compared to the films of the 1980s and 90s.

Verhoeven, in a recent interview with The Sunday Times, decried this “new purity” in Hollywood. He specifically called out Marvel superhero movies and the most recent James Bond film for their lack of eroticism: “There was always sex in Bond! They did not show a breast, or whatever. But they had some sex.” It is hard to imagine Paloma, the ass-kicking bubbly ingénue Ana de Armas plays in No Time to Die, not having sex with 007 if she had appeared in an earlier installment of the franchise, but in the 2021 spy thriller, they don’t even share a kiss. Verhoeven’s not alone; many others, both in the industry and outside it, have voiced similar criticisms.

In no genre is this shift more acutely felt than the horror genre. The recent disappointing remake of Hellraiser, for example, shines a light on this odd quirk of our times. Clive Barker’s original film from 1987, based on his novella The Hellbound Heart, features a mysterious puzzle box that summons a group of Cenobites, hellish angel-demons that seem like they could have been borne from the disturbing fantasies of the regulars at Mineshaft (the famed gay leather bar of 1980s New York City). These extra-dimensional fetishists, who don’t recognize any difference between pleasure and pain, claim to explore “the further regions of experience.” The film is a glorious fever dream of sadomasochistic enticement and revulsion.

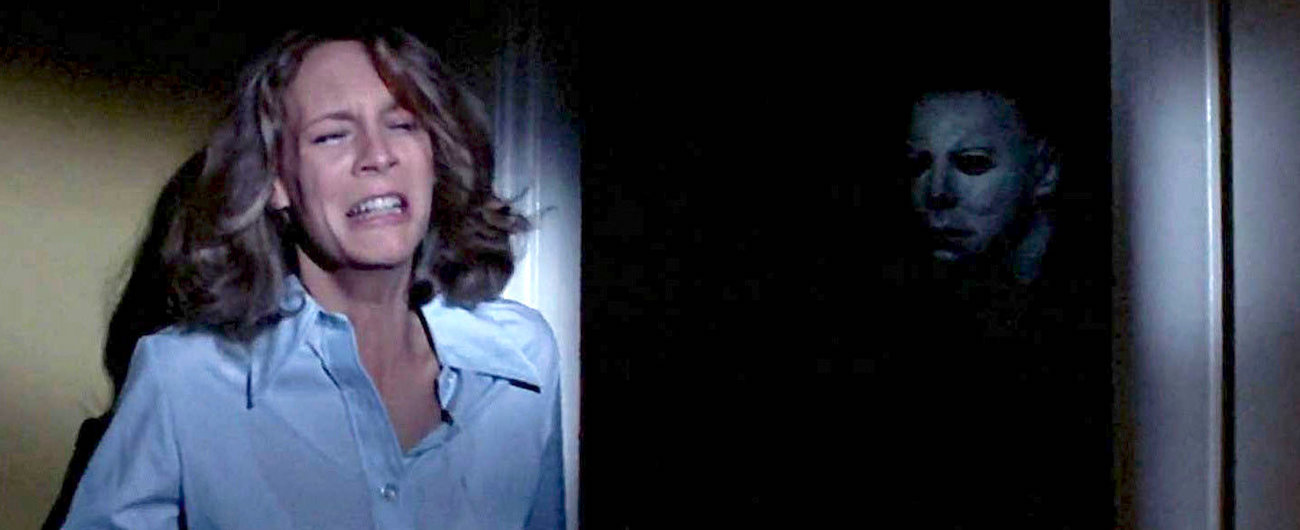

Though David Bruckner’s 2022 remake pays minor lip-service to “the further regions of experience,” the erotic implications of the pleasure-pain binary are largely abandoned. The original’s sleazy sex nightmare is simplified into a half-baked drug allegory that is almost entirely sexless. Similarly, David Gordon Green’s new Halloween trilogy, which recently concluded with Halloween Ends, is mostly devoid of fornication. This from the franchise that pretty much started—even if unintentionally—the trend of “Sex = Death” horror that came to define the slasher subgenre for two decades or more.

There are innumerable hot takes about the asexuality of contemporary cinema as a response to the #MeToo movement. The idea is that a fear of the ramifications of objectifying young women or saying anything complex about sex that might offend the pearl-clutchers on either side of the political spectrum has neutered the genre. Though I agree that these phenomena are not entirely unrelated, I think it’s probably too facile an answer. This trend was already in the air long before 2017, when news of Harvey Weinstein’s years of predation rocked the industry—and then the world.

The accessibility of pornography may have had as much of an impact. Part of what made the erotic such an integral aspect of a century of scary movies was that the horror genre was the main genre of transgression. The twin transgressions of sex and violence could couple up and make their home in these films, when other genres generally avoided them or treated them with surface-level interest.

Though most of the people that Michael Myers murders in Halloween do partake in sexual intercourse before they meet their doom, it needn’t be read as payment for sin.

But in the age of Pornhub and 8chan—not to mention the nether regions of the Dark Web—where every possible sexual proclivity and violent curiosity can be consumed in short clips just a few keystrokes away, there is nothing a horror film can show us that we can’t see more graphically online.

Accessibility in all things, including sex, defines our time. Anything can be procured whenever we want without much effort. Not only can any video be watched, but products (from food to sex toys, and everything in between) can appear at our doorstep with little to no human interaction. Friendship is mediated through screens—thus, losing much of its meaning now that the word is used to define any number of loose relationships we share with acquaintances and strangers. Courtship, too, is now mostly done with the swipe of a finger. There is no delay, no absence, no mystery. Everything is ever-present, and that is why so little of it has value.

What makes sex alluring is its attempt (even if inevitably unsuccessful) at reconciling a mystery, a tension, an absence, for desire presupposes a lack; when sex is ever-present, it might as well be nonexistent.

It may seem reasonable, then, to argue that if sex is already omnipresent and ever-accessible in our lives, then we may not need it in our cinemas. That would be a mistake. No matter how prevalent sex is or isn’t, no matter how permissible a society may or may not be, existence is predicated upon the erotic, so the cultural myths of a healthy society must tussle with our libidinal entanglements. Removing sex from the bestiary of the horror genre is a solution to a nonexistent problem, one that undoubtedly begets real problems.

II.

A Crowded Theater

In Sexual Personae, her magnum opus on art and decadence, Camille Paglia writes:

The ghost-ridden character of sex is implicit in Freud’s brilliant theory of “family romance.” We each have an incestuous constellation of sexual personae that we carry from childhood to the grave and that determines whom and how we love or hate. Every encounter with friend or foe, every clash with or submission to authority bears the perverse traces of family romance. Love is a crowded theater.

Libidinal energy both draws us to and estranges us from the world. The enigmatic process of cathexis may attach us to material (people and things), but it also acts as a séance, endeavoring contact with apparitional archetypes, spectral symbolism. When eros is made physical through sex, it becomes, in Paglia’s words, a “ritualistic acting out of vanished realities.” But she also notes that “there can never be a purely physical or anxiety-free sexual encounter.” The revenants of our family romance cannot be exorcised.

Our experiences with the material world are always infused with our personal erotic cosmology—the mysteries of which, like those of the universe at large, are mostly unknown (and likely unknowable). Sex, therefore, is simulacrum—a performance of vestigial roles, a pantomime of occulted inclinations.

Horror films are simulacra too, lurid representations of our deepest anxieties, our secret torments, our primal fears. As Paglia says of sex, horror films are “fraught with symbols,” “shaped by psychic shadows,” and haunted by “hostility and aggression.”

“You never have sex. The minute you get a little nookie, you’re as good as gone. Sex always equals death.”

In these shared cinematic nightmares that emerge from the projector, the occulted world that terrifies us is given image and sound. As we face our dreads and desires surrounded by others that we only faintly perceive in the dark of the theater, we are in some way reenacting love’s crowded theater. The monsters and maniacs that stalk the silver screen are all found in eros too. Sex contains the madman’s anxiety, the slasher’s brutality, the demon’s possession, the werewolf’s bestial transformation, the vampire’s exchange of bodily fluids, the zombie’s mindless insatiability, and the ghost’s persistent looming.

If horror, as a genre, is more commonly associated with violence than sex, that is because the one transgression overshadows the other. But that which is hidden only burrows deeper into the unconscious. All horror is the horror of sexual desire.

III.

Eros in the Quiver

Even before Count Dracula first vanted to suck your blood, the horror genre—which, more than any other genre, is an extension of our ancient myths and primal anxieties—had given people a way to perceive, contemplate, and grapple with the sexual topics that polite society shies away from, whether its something as innocuous as the confounding rituals of courtship or something more perilous like the enticement of taboo, transgression, and savagery.

The animal-nature of desire—its wildness, its uncontrollability—has coursed through the veins of the genre from its nascency, even when Hollywood had more rules about what could and could not be shown onscreen.

Dracula biting a neck in the 1931 adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel, exchanging bodily fluids, is already erotic enough: “My blood now flows through your veins.” But his transformation into animal gives the sexual undercurrent a bestial image. When Van Helsing holds a mirror up to the titular count, who slaps it to the floor and storms out, John Harker says, “Did you see the look on his face? Like a wild animal!” When Harker sees a wolf running across the lawn moments later, Van Helsing explains of vampires, “Sometimes they take the form of wolves but generally of bats.”

Of course, Dracula is not the only Universal Pictures monster whose desires emerge as animal: “Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night may become a wolf when the wolfsbane blooms and the Autumn moon is bright.” Though little of the original 1941 version of The Wolf Man dealt explicitly with sex, the idea that even a good Christian man who is “pure of heart” and “says his prayers” could fall prey to his own insatiable animal cravings established a template for future therianthropic terrors.

The following year, in an attempt to encroach on the Universal horror market, RKO Studios gave producer Val Lewton his own horror unit. As part of the deal, Lewton had to follow three rules: the films would have a small budget (under $150,000), their runtime would not exceed 75 minutes, and their titles would be provided by his supervisors at RKO, with the films then built around those titles. The first title they gave him was “Cat People.” They undoubtedly expected Lewton would make a copycat of The Wolf Man, but he gave them something simultaneously more unsettling and more erotic.

In Cat People, Irena Dubrovna, a Serbian immigrant, meets and falls in love with Oliver Reed, “a good plain Americano,” but an ancient curse on her people warns that she may turn into a panther when sexually aroused. Though the violence and sex are entirely offscreen, the terror and anxiety they elicit seep through every frame—a masterclass in chillingly erotic noir atmospherics. The meaning is, as with all great horror films, ambiguous: it is as much a warning of the dangers of sexual repression as it is a warning of the dangers of sexual desire.

Sexual repression vibrates just beneath the surface of many horror films—and often erupts, shattering that surface. If, as Freud claimed, “the essence of repression lies simply in turning something away, and keeping it at a distance, from the conscious,” then Norman Bates, from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 shocker Psycho, may be the poster boy of sexual repression. After committing matricide, if Bates desires any woman besides his mother, he takes on his mother’s personality and commits violence against the object of sexual desire. Dr. Richmond, the psychiatrist who shows up at the end of the film, explains to Lila Crane, the victim’s sibling:

When Norman met your sister, he was touched by her, aroused by her. He wanted her. And this set off his jealous mother and mother killed the girl. After the murder, Norman returned as if from a deep sleep. And, like a dutiful son, covered up all traces of the crime he was convinced his mother had committed.

Maybe a poster boy’s best friend really is his mother? The incestuous family romance on display in Psycho’s Oedipal drama shows up again and again in the genre, sometimes through a metaphorical incest, other times it becomes alarmingly literal, as in the 1982 remake of Cat People, which reimagines the story as a much sleazier affair by giving the female protagonist a brother who is also a werecat and wants to mate with his sister (since only incestuous copulation prevents their transformation into panthers).

Sex as sinful act that leads to death was nothing new in the 1970s, but in the latter half of that decade (perhaps in response to the free-love 60s) it did emerge as a staple of horror cinema.

Psycho also clues us into another unresolved issue in the sex-as-horror catalog: how the voyeuristic impulse affects the erotic theater. What initially turns Bates on, what forces him to become mother to enact murder, is his spying on Marion Crane through a peephole as she undresses. Peeping Tom, which came out mere months before Psycho, takes Bates’s lascivious voyeurism even further by making its central psycho, Mark Lewis, a cameraman. Lewis not only films his murders, but uses a knife sheathed in one the legs of his tripod to stab his victims. The camera kills. The film asks whether we, too, puncture the objects of desire that we ogle.

The objects of our desire always remain a mystery to us, even—and perhaps especially—if we marry them. Harold Bloom explains that “We can never embrace (sexually or otherwise) a single person, but embrace the whole of her or his family romance.” But in that embrace, whatever wraiths surround the act, we cannot know, for the other’s sexual dreams, their latent impulses, their web of erotic entanglements are foreign to us and will forever be.

This discomfiting reality is what Stanley Kubrick mines in his final film, Eyes Wide Shut. At the end of the movie, after a night where Bill Harford and his wife Alice both learn how little the other knows about their inner erotic lives, Alice tells Bill, “The important thing is we’re awake now, and hopefully for a long time to come.” But the title undercuts this potential revelation: awake or asleep, when we’re viewing the other, aren’t we always viewing them with eyes wide shut?

Of course, objects of desire needn’t always be human. In fact, they needn’t even be alive. The horror genre often explores, directly or indirectly, the sexual allure of objects: various weapons, yes, but also statues, dolls, food, cameras, modes of transportation, and all manner of new technology. The automobile is often particularly bewitching.

In Christine, a 1958 Plymouth Fury comes to life and commits murder; in Titane, a Cadillac impregnates the protagonist. (This is just one horrifying pregnancy among many in the genre. Alien and Rosemary’s Baby offer vastly different natal nightmares. The fear of the byproducts of sex—be they STDs, pregnancy, children, or social ostracism—are never far from the screen, even when they don’t take centerstage.)

David Cronenberg’s Crash, the ultimate in auto erotica, explores a sub-culture of pansexual car-crash obsessives. For them, the auto accident is “a fertilizing rather than destructive event.” The car crash as form of sexual intercourse points to one of the more disturbing questions underlying sex in horror: How does trauma, violence, power, and pain shape our sexual desires?

“While violence cloaks itself in a plethora of disguises,” according to the opening narration of Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, “its favorite mantle still remains sex.” In films as varied as Jennifer’s Body, The Last House on the Left, and The Night Porter this question is broached (though answers—surprise, surprise—remain elusive). But through the erotics of violence, we can see that the sex and death drives may not be as oppositional as they at first seem. Their relationship is not a straightforward one; it’s a relationship that begs for interrogation, an interrogation that horror films are wont to provide.

IV.

My Sex, My Executioner?

In the poem, “My Son, My Executioner,” Donald Hall sees his newborn child as the architect of his death. Of course, this is not a poem of literal patricide, but one that explores the nature of senescence. The son is a reminder of personal mortality, even though he is also, paradoxically, an “instrument of immortality.”

But even without the byproduct of an offspring, horror films make clear that sex is an executioner whose “cries and hunger document our bodily decay.” Sex reminds us of our mortality, our humanness, our bestiality. As we seek to fill the void of our being, to overcome our deficient animal nature, we give into that animal nature most completely. In the throes of passion, we may for a moment seem to touch the divine, to transcend the tyranny of time and body, but even this moment—this petit mort—gets us nowhere but disappointment, for desire can never truly be satiated.

Sex reminds us of our mortality, our humanness, our bestiality. As we seek to fill the void of our being, to overcome our deficient animal nature, we give into that animal nature most completely.

Though It Follows has been read as both an allegory of sexual trauma and STDs, a simpler (but no less powerful) analysis of the film finds a resonance in Hall’s poem. What the amorphous It that follows Jay Height after her sexual encounter might represent is merely the realization of mortality upon sexual maturity. When Jeff Redmond, the boyfriend who passed the following It onto her, is asked who in a movie theater he would want to be if he could swap places with anyone, he chooses a child because the kid “has his whole life ahead of him.” Once we’ve achieved sexual maturity, the countdown to our destruction becomes apparent—it follows us like an apparition.

Eros and thanatos—the twin Freudian drives—are often intertwined in the genre, but not always in the same way. Elsewhere, they’re tied into a more religious knot. In Carrie, Brian de Palma’s 1976 adaptation of the novel by Stephen King, the mother of the titular protagonist preaches to her daughter that “the first sin was intercourse.” This is an odd reading of the Bible, but not one without antecedents.

Though the “original sin” is generally accepted to be Adam and Eve’s eating of the forbidden fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, those who subscribe to the fringe Christian “Serpent Seed” doctrine see Eve’s tasting of the forbidden fruit as a metaphor for sex. In their belief, she mated with the serpent; therefore, the first sin was intercourse.

Sex as sinful act that leads to death was nothing new in the 1970s, but in the latter half of that decade (perhaps in response to the free-love 60s) it did emerge as a staple of horror cinema. John Carpenter’s Halloween—and its central character, Laurie Strode—set up the model of the “final girl” who survives because she was virginal and studious.

As the popularity of the slasher subgenre exploded post-Halloween, many productions followed the formula: Sex = Death. The Friday the 13th franchise codified the rule where good Christian morals (no sex, no drugs) somehow equalled survival, as if God was looking down on Camp Crystal Lake and thinking, I’ll let Jason Voorhees get this one because she’s a strumpet, but not this other girl who hasn’t done the deed yet.

This simple moralistic connection between sex and death was its most prevalent in the 1980s—a time when the “Moral Majority” was on the rise, Reagan conservatism ruled the day, and AIDS terrified the world. It should surprise no one that horror movies of the era incorporated the prevailing priggish sentiment—this is what horror movies are meant to do: engage with the cultural mores of the time and place from which they emerge, tying those timely perspectives to more timeless existential dreads. So even as movies like Friday the 13th seem to endorse the Christian Right’s puritanical views of sex, they do so while engaging in the very prurient interests that those ideologies oppose.

By the time Wes Craven made his meta-slasher film Scream in the mid-90s, the “Sex = Death” formula was such a common trope that the character Randy Meeks, a horror-obsessed cinephile, places it at the top of his list of rules for successful horror-movie survival: “You never have sex. The minute you get a little nookie, you’re as good as gone. Sex always equals death.” The film breaks the rule.

When we’re first introduced to Sidney Prescott she seems like a classic final girl. Though she has a boyfriend, she has an “underwear rule,” where they don’t go past second base. He complains how watching The Exorcist at home on television reminds him of their relationship: “Yeah, it was edited for TV. All the good stuff was cut out, and I started thinking about us and how two years ago, we started off kinda hot and heavy, a nice solid R rating on our way to an NC-17. And how things have changed and, lately, we’re just sort of… edited for television.”

She holds out for a while, but she eventually gives in and has sex with him by saying that she doesn’t want to be in a horror movie: “Why can’t I be a Meg Ryan movie? Or even a good porno.” Scream broke the overdetermined link between sex and death that had stifled the slasher subgenre. If horror films are meant to wrestle with eros and thanatos, then the “Sex = Death” formula could never last. It was too simple a formulation for such a complex problem.

John Carpenter, whose film Halloween is credited with putting the trope in place, always denied this view. Though most of the people that Michael Myers murders in Halloween do partake in sexual intercourse before they meet their doom, it needn’t be read as payment for sin. (If doing drugs is a sin, Laurie Strode smokes pot and doesn’t die.) Sex may, after all, just be another distraction, and distracted people are easy targets, so they’re the ones who get sliced and diced in slasher films.

Carpenter maintains that the “Sex = Death” reading is the product of viewers projecting their own religious guilt onto the film. In this way, I don’t think reading sex into Myers’s motivation for murder is inherently wrong because horror films are meant to be projections of our own hang-ups, yearnings, and fears—and Myers does look at his sister’s unmade, just-fucked-in bed before he murders her (his first victim). But Myers must be more than mere punishment for sin. You can fill his shape with that explanation if you like, but The Shape contains multitudes. Such simple 1-to-1 correlations are more the purview of X=Y psychologism than of great art.

The caricature of psychoanalysis—what might be called the Spellbound model, where every dream allows us to “open the locked doors of [the] mind” through simple X=Y associations, where every cigar is a phallus and every dictator a daddy—sees sex as the answer to everything. The truth is something much more unnerving.

Yes, the erotic haunts all existence like a specter. Being is merely the catalog of innumerable attempts to fulfill our unfulfillable desires. But sex is not the answer to everything, it is merely the question—a question whose unanswerability is the foundation of all horror, the question from which all other questions emerge.

Tyler Malone

Tyler Malone is a writer based in Southern California. He is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of The Scofield as well as a Contributing Editor at Literary Hub. His writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Lapham’s Quarterly, the LA Review of Books, and elsewhere.