Moving Through New York's Early 20th-Century Gay Spaces

From Rooming Houses to the YMCA

When Willy W. arrived in New York City in the 1940s, he did what many newcomers did: he took a room at the 63rd Street YMCA. As was true for many other young men, the friends he made at the Y remained important to him for years and helped him find his way through the city. Most of those friends were gay, and the gay world was a significant part of what they showed him. He soon moved on, though, to the St. George Hotel in Brooklyn, which offered more substantial accommodations. The St. George, it seemed to him, was “almost entirely gay,” and the friends he met there introduced him to yet other parts of the gay world.

After living briefly in a rooming house on 50th Street near Second Avenue, he finally took a small apartment of his own, a railroad flat on East 49th Street near First Avenue, where he stayed for years. He moved there at the invitation of a friend he had met at Red’s, a popular bar on Third Avenue at 50th street that had attracted gay men since its days as a speakeasy in the 1920s. The friend had an apartment in the building and wanted Willy to take the apartment next to his. An elderly couple had occupied it for years, and, since the walls were rather thin, the friend had never stopped worrying that they heard him late at night with gay friends and had grown suspicious of the company he kept. When they moved out he wanted to make sure that someone more understanding would take their place. Willy was happy to do so, and as other apartments opened up in the building he invited other friends to move in. Several friends did, and some of the newcomers encouraged their own friends to join them.

The building’s narrow railroad flats, if not luxurious, were adequate and cheap; the location, near the gay bar circuit on Third Avenue in the East 50s, was convenient; and most important, the other inhabitants were friendly and supportive. Within a few years, Willy remembered, “we took over.” Gay men occupied 14 of the 16 apartments in the building. This was not the only predominantly gay apartment building Willy remembered. In the 1950s a major apartment house at Number 405 in a street in the East 50s was so heavily gay that gay men nicknamed it the “Four out of Five.”

Willy not only lived in a gay house, but in a growing gay neighborhood enclave, whose streets provided him with regular contact with other gay men. Although Willy’s success in creating an almost completely gay apartment building was unusual, his determination to find housing that maximized his autonomy and his access to the gay world was not. In his movement from one dwelling to the next, Willy traced a path followed by many gay men in the first half of the century as they built a gay world in the city’s hotels, rooming houses, and apartment buildings, and in its cafeterias, restaurants, and speakeasies. Gay men took full advantage of the city’s resources to create zones of gay camaraderie and security.

*

Although living with one’s family, even in a crowded tenement, did not prevent a man from participating in the gay world that was taking shape in the city’s streets, many gay men, like Willy, sought to secure housing that would maximize their freedom from supervision. For many, this meant joining the large number of unmarried workers living in the furnished-room houses (also called lodging or rooming houses) clustered in certain neighborhoods of the city. No census data exist that could firmly establish the residential patterns of gay men, but two studies of gay men incarcerated in the New York City Jail, conducted in 1938 and 1940, are suggestive. Sixty-one percent of the men investigated in 1940 lived in rooming houses, three-quarters of them alone and another quarter with a lover or other roommates; only a third lived in tenement houses with their own families or boarded with others.

Some landladies doubtless tolerated known homosexual lodgers for the same economic reasons they tolerated lodgers who engaged in heterosexual affairs, and others simply did not care.

Court records from the first three decades of the century provide relatively few accounts of men apprehended for sexual encounters in rooming houses (itself indirect evidence of the relative security of such encounters), but they do abound in anecdotal evidence of men who lived together in rooming houses or took other men to their rooms, and whose relationships or rendezvous came to the attention of the police only because of a mishap. Such information most frequently came to the attention of the police when a man who had been brought home assaulted or tried to blackmail his host, when parents discovered that a man had invited their son home, when the police followed men to a furnished room from some other, more public locale, or when one of the tenants sharing a room with his lover was arrested on another charge.

Usually situated in rowhouses previously occupied by single families, rooming houses provided tenants with a small room, a bed, minimal furniture, and no kitchen facilities; residents were expected to take their meals elsewhere. Such housing had qualities that made it particularly useful to gay men as well as to transient workers of various sorts. The rooms were cheap, they were minimally supervised, and the fact that they were usually furnished and were rented by the week made them easy to leave if a lodger got a job elsewhere—or needed to disappear because of legal troubles.

Rooming houses also offered tenants a remarkable amount of privacy. Not only could they easily move out if trouble developed, the tenants at most houses compensated for the lack of physical privacy by maintaining a degree of respectful social distance. (Inclined to dislike anything they saw in the rooming houses, housing reformers, somewhat contradictorily, were as distressed by the lack of interest roomers took in one another’s affairs as by the lack of privacy the houses afforded.) One study conducted in Boston in 1906 reported that in addition to taking their meals outside their cramped quarters, most roomers also developed their primary social ties elsewhere, at cheap neighborhood restaurants, at their workplaces, and in saloons. Moreover, the absence of a parlor (which usually had been converted into a bedroom) in most rooming houses, the respect many landladies had for their tenants privacy, and, perhaps most important, the competition among rooming houses for lodgers led many landladies to tolerate men and women visiting each other’s rooms and bringing in guests of the other sex. Numerous landladies in the 1920s, when queried by male investigators posing as potential tenants, said straightforwardly that they could have women in their rooms: “Why certainly, this is your home” was the reassuring reply of one.

Some landladies doubtless tolerated known homosexual lodgers for the same economic reasons they tolerated lodgers who engaged in heterosexual affairs, and others simply did not care about their tenants’ homosexual affairs. But most expected their tenants at least to maintain a decorous fiction about their social lives. The boundaries of acceptable behavior were, as a result, often unclear, and in many houses men felt constrained to try to conceal the gay aspects of their lives.

Moral reformers expressed concern that the casual intermingling of strangers in furnished-room houses could “assume a dangerous aspect.”

The story of one black gay man who lived in the basement of a rooming house on West 50th Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, in 1919 suggests the latitude—and limitations—of rooming-house life. The tenant felt free to invite men whom he met on the street into his room. One summer evening, for instance, he invited an undercover investigator he had met while sitting on the basement stairs. But, as he later explained to his guest, while three “young fellows” had been visiting him in his room on a regular basis, he had finally decided to stop seeing the youths because they made too much noise, and he did not want the landlady “to get wise.” Not only might he lose his room, he feared, but also his job as the house’s chambermaid. The consequences of discovery could be even more severe. In 1900 a suspicious boardinghouse keeper on East 13th Street barged into a room taken only a few days earlier by two waiters, a 20-year-old German and a 17-year-old American. She caught them having sex, had them arrested, and eventually had the German sent to prison for a year.

In general, though, the same lack of supervision in the rooming houses that so concerned moral reformers made the houses particularly attractive to gay men, who were able to use their landladies’ and fellow tenants’ presumption that they were straight in order to disguise their liaisons with men. A male lodger attracted less attention when a man, rather than a woman, visited his room, and a male couple could usually take a room together without generating suspicion. Moreover, the privacy and flexibility such accommodations provided often helped men develop gay social networks. Young men new to New York or the gay life often met other gay men in their rooming houses, and these men sometimes served as their guides as they explored gay society. The ease with which men could move from one rooming house to another also allowed them to pursue and strengthen new social ties by moving in with new friends (or lovers) or moving closer to restaurants or bars where their friends gathered.

Moral reformers expressed concern that the casual intermingling of strangers in furnished-room houses could “assume a dangerous aspect,” especially when it introduced young men and women to people of ill repute. In response to this threat, some sought to offer more secure environments to young migrants to the city. Various groups established special hotels at the turn of the century in order to provide men with moral alternatives to the city’s flophouses, transient hotels, and rooming houses.

Ironically, though, such hotels often became major centers for the gay world and served to introduce men to gay life. In an all-male living situation, in which numerous men already shared rooms, it was virtually impossible for management to detect gay couples. The Seamen’s Church Institute, for instance, had been established as a residential and social facility by a consortium of churches in order to protect seamen from the moral dangers the churchmen believed threatened them in the lodging houses of the waterfront areas. But, as we have already seen, gay seamen and other gay men interested in seamen could usually be found in the Institute’s lobby. Men involved in relationships also had no difficulty taking rooms together: one seamen told an investigator in 1931 that he had lived with a youth at the Institute “for quite some time,” and he had apparently encountered no censure there.

Similarly, the two massive Mills Houses, built by the philanthropist Darius O. Mills, were intended to offer unmarried workingmen moral accommodation in thousands of small but sanitary rooms. (The first one was built in 1896 directly across Bleecker Street from the building that had housed the notorious fairy resort, the Slide, just a few years earlier, as if to symbolize the reestablishment of moral order on the block; the second was built on Rivington Street in 1897.) Its attractiveness as a residence for working-class gay men is suggested by the frequency with which its residents appeared in the magistrate’s courts. In March 1920, for instance, at least three residents of the two Mills Houses were arrested on homosexual charges (not on the premises): a 43-year-old Irish laborer, a 42-year-old Italian barber, and a 38-year-old French cook.

If you go to a shower there is always someone waiting to have an affair. It doesn’t take long.

The residential hotels built by the Young Men’s Christian Association provide the most striking example of housing designed to reform men’s behavior that gay men managed to appropriate for their own purposes. The YMCA movement had begun in the 1840s and 1850s with the intention of supplying young, unmarried migrants to the city with an urban counterpart to the rural family they had left behind. Its founders had expressed special concern about the moral dangers facing such men in the isolation of rooming-house life. The Y organized libraries, reading groups, and gymnasiums for such men, and in some cities established residential facilities, despite some organizers’ fears that they might become as depraved and degrading as the lodging houses. The New York YMCA began building dormitories in 1896, and by the 1920s the seven YMCA residential hotels in New York housed more than 1000 young men, whose profiles resembled those of most rooming-house residents: primarily in their twenties and thirties, nearly half of them were clerks, office workers, and salesmen, while smaller numbers were “professional men,” artisans, mechanics, skilled workers, and, especially in the Harlem branch, hotel, restaurant, and domestic-service employees.

The fears of the early YMCA organizers were realized. By World War I, the YMCAs in New York and elsewhere had developed a reputation among gay men as centers of sex and social life. Sailors at Newport, Rhode Island, reported that “everyone” knew the Y was “the headquarters” for gay men, and the sailor’s line in Irving Berlin’s World War I show, Yip, Yip, Yaphank, about having lots of friends at the YMCA is said to have drawn a knowing laugh. The reputation only increased in the Depression with the construction, in 1930, of two huge new YMCA hotels, which soon became famous within the gay world as gay residential centers. The enormous Sloane house, on West 34th Street at Ninth Avenue, offered short-term accommodations to “transient young men” in almost 1,500 rooms, and the West Side Y, on 63rd Street at Central Park West, offered longer-term residential facilities as well. A man interviewed in the mid-1930s recalled of his stay at Sloane House:

One night when I was coming in at 11:30PM a stranger asked me to go to his room. They just live in one another’s rooms although it’s strictly forbidden. . . . This YMCA is for transients but one further uptown [the West Side Y] is a more elegant brothel, for those who like to live in their ivory towers with Greek gods. If you go to a shower there is always someone waiting to have an affair. It doesn’t take long.

Such observations became a part of gay folklore in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, when the extent of sexual activity at the Ys—particularly the “never ending sex” in the showers—became legendary within the gay world. A man living in New Jersey remembered that he stayed at Sloane House “many times, every chance I got . . . [because] it was very gay”; another man called it a “gay colony.” Indeed, the Y had such a reputation for sexual adventure that some New Yorkers took rooms at Sloane House for the weekend, giving fake out-of-town addresses. “It was just a free for all,” one man who did so several times recalled, “more fun than the baths.”

While the sexual ambience of the Ys became a part of gay folklore, the role of the Ys as gay social centers was also celebrated. Many gay New Yorkers rented rooms in the hotels, used the gym and swimming pool (where men swam naked), took their meals there, or gathered there to meet their friends. Just as important—and more ironic, given reformers’ intentions—was the crucial role the hotels often played in introducing young men to the gay world. It was at the Y that many newcomers to the city made their first contacts with other gay men. Grant McGree arrived in the city in 1941, not knowing anyone, intimidated by the size of the city, and full of questions about his sexuality. But on his first night at the Y as he gazed glumly from his room into the windows of other men’s rooms he suddenly realized that many of the men he saw sharing rooms were couples; within a week he had met many of them and begun to build a network of gay friends. As many gay men used to put it, the letters Y-M-C-A stood for “Why I’m So Gay.”

__________________________________

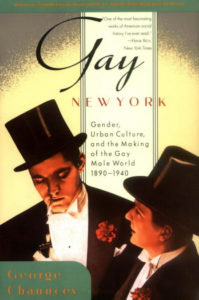

Adapted excerpt from Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 by George Chauncey. Copyright © 2019. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

George Chauncey

George Chauncey is a professor of history at Columbia University and the Director of the Columbia Research Initiative on the Global History of Sexualities. Gay New York, his first book, won the distinguished Turner and Curti Awards from the Organization of American Historians, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the Lambda Literary Award. He is also the author of Why Marriage? Chauncey lives in New York City.