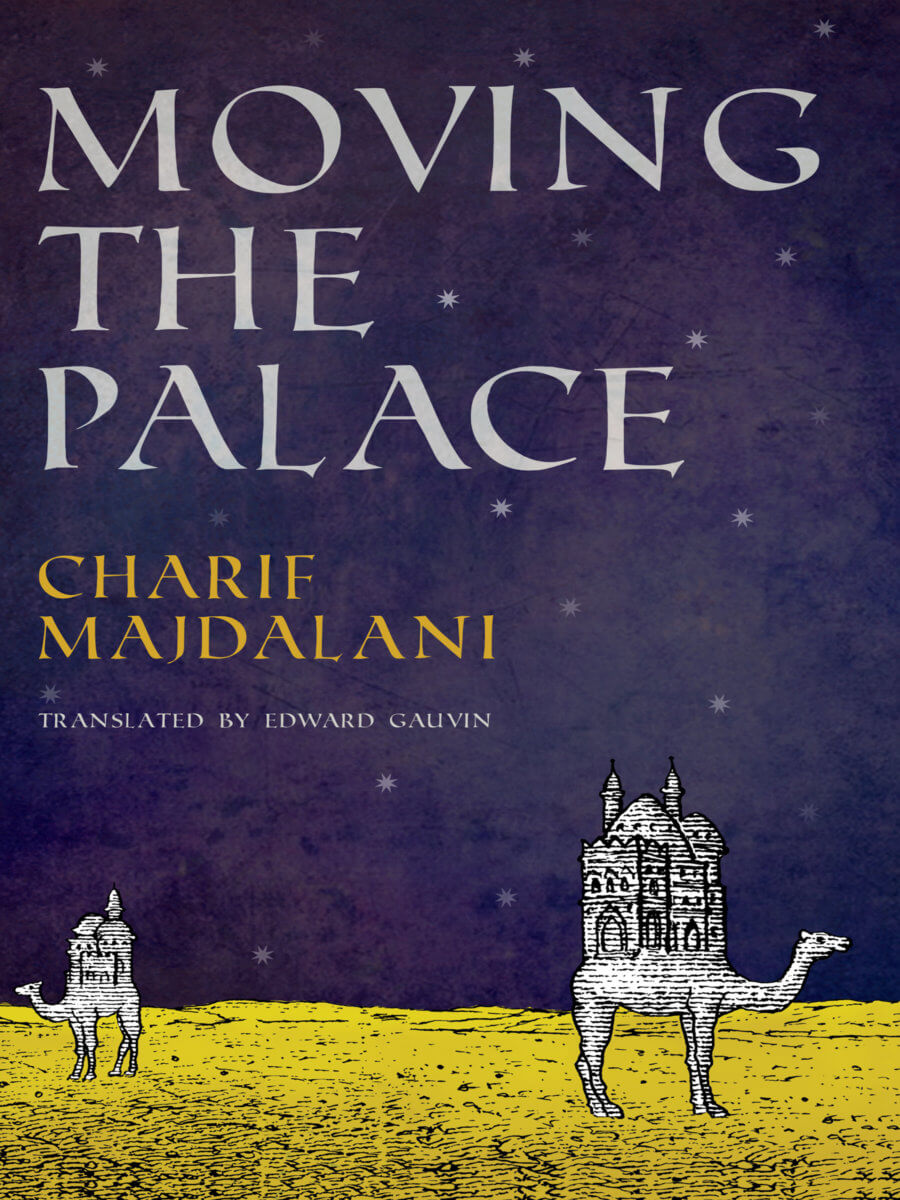

This is a tale full of mounted cavalcades beneath great wind-tossed banners, of restless wanderings and bloody anabases, he thinks, musing on what could be the first line of that book about his life he’ll never write, and then the click-clack of waterwheels on the canal distracts him; he straightens in his wicker chair and leans back, savoring from the terrace where he’s sitting the silence that is a gift of the desert the desert spreads in its paradoxical munificence over the plantations, the dark masses of the plum trees, the apricot trees, the watermelon fields, and the cantaloupe fields, a silence that for millennia only the click-clack of waterwheels has marked with its slow, sharp cadence. And what I think is, there may or may not be apricot orchards or watermelon fields, but that is most definitely the desert in the background of the photo, the very old photo where he can be seen sitting in a wicker chair, cigar in hand, gazing pensively into the distance, in suspenders, one leg crossed over the other, with his tapering mustache and disheveled hair, the brow and chin that make him look like William Faulkner, one of the rare photos of him from that heroic era, which I imagine was taken in Khirbat al Harik, probably just after he’d come from Arabia, though in fact I’m not at all sure, and really, what can I be sure of, since apart from these few photos, everything about him from that time is a matter of myth or exaggeration or fancy? But if I am sure of nothing, then how should I go about telling his story; where shall I seek the Sultanate of Safa, vanished from the memory of men but still bound up with his own remembrances; how to imagine those cavalcades beneath wind-tossed banners, those Arabian tribes, and those palaces parading by on camelback; how to bring together and breathe life into all those outlandish, nonsensical particulars uncertain traditions have passed down, or vague stories my mother told me that he himself, her own father, told her, but which she never sought to have him clarify or fasten to anything tangible, such that they reached me in pieces, susceptible to wild reverie and endless novelistic embroidering, like a story of which only chapter headings remain, but which I have waited to tell for decades; and here I am, ready to do so, but halting, helpless, daydreaming as I imagine he daydreams on the verandah of that plantation in Khirbat al Harik, watching unfold in his memory that which I will never see, but shall be forced to invent?

* * * *

Yet his story, at the start, hardly differs from those of any other Lebanese emigrants who, between 1880 and 1930, left their homeland to seek adventure, fame, or fortune in the world. If many of them met with success thanks to trade and commerce, there were some whose stories retained a more adventurous note, such as those who braved the Orinoco to sell the goods of civilization to peoples unknown to the world, or those who were heroes of improbable odysseys in the far Siberian reaches during the Russian civil wars. He was one of these, who came back at last with his eyes and head full of memories of escapades and follies. Tradition has it that he left Lebanon in 1908 or ’09. He could’ve headed for the United States or Brazil, as did most, or for Haiti or Guyana, as did the most courageous, or for Zanzibar, the Philippines, or Malabar, as did the most eccentric, those who dreamed of making fortunes trading in rare or never-before-seen wares. Instead, he chose the most thankless land known at the time, and headed for the Sudan. But back then, the Sudan offered immense opportunities to a young Lebanese man who was Westernized, Anglophone, and Protestant to boot. And he was these three things, the child of an ancient family of Protestant poets and littérateurs, originally Orthodox Christians from the Lebanese mountains, poets and littérateurs who, when the winds of revival wafted through Eastern philosophy, wrote treatises on the modernization of tropes in Arab poetry, whole divans of poems, and even an Arabic-English dictionary. Of his childhood, nothing is recorded; this much, however, is: at the age of eighteen he began his studies at the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut. After that, the ancient name he bore was not to open the doors to any career path other than a scholar’s, attended by some unremarkable post in the service of the Ottoman administration. This, it seemed, would not suffice him. Like the conquistadors who left a Europe that could no longer contain them, he left Lebanon one spring morning in 1908 or ’09, no doubt taking with him in a small suitcase a few shirts and handkerchiefs, and in his head a few delicate memories, the trees in the garden of the familial abode where a salt wind echoed the stately meter of the open sea, the aromas of jasmine and gardenia, the skies above Beirut vast and mild as a woman’s cheek, and the liturgical whiteness of the snows on Mount Sannine.

* * * *

In those inaugural years of the 20th century, the Sudan has just been retaken by Anglo-Egyptian armies, who put an end to Khalifa Abdallahi’s despotic regime, and returned the land to Egypt. Confusion still reigns, the country is only half under control, the reconstruction of the ruined former capital has barely begun. But after decades of obscurantist tyranny, a new world is being born, and in the flood of men showing up to seize the still innumerable opportunities are a few from Lebanon: merchants, smugglers, artisans. But he is not one of these. The oldest accounts about the man who would become my grandfather report that he was a civilian officer in the Sudan, and it was in that capacity, no doubt, that he would live out the fantastical adventures attributed to him. Just as it reached Sudan, the British Army was in fact starting to recruit Anglophone Christian Arabs of Lebanese origin to act as liaisons with the local populace. Considered civilian officers, these intermediary agents were first assigned to the Egyptian Ministry of War in Cairo before being dispatched to their postings in Khartoum.

This means that at first—that is, the day he arrived in Khartoum—my grandfather had come from Cairo, after thirty hours of vile dust and soot tossed backward in black plumes by locomotives first of the Cairo-Luxor line, then the Luxor-Wadi Halfa, then the Wadi Halfa-Khartoum. Here he is, stepping off the train, covered in dust right up to the pockets of his white suit jacket, sand in his eyes and nostrils, the same amused air as in the photo I mentioned, with his trim mustache and Faulknerian brow, though for all that, hair neatly combed and suitcase in hand. For a mallime, a massive Sudanese man in white robes sees to dusting him off with a great feather, after which a British officer politely waiting in the wings steps forward to ask, “Mr. Samuel Ayyad?” And like that he is taken in hand, conveyed to the barge that crosses the Blue Nile, then to Khartoum itself, and then, in a carriage, through the construction site that is the city to a white, new, unfinished villa where he must make his way over piles of brick and goatskins filled with cement, getting his shoes all dusty again, though not with the usual brown dust, but rather the white powdery dust of plaster. “One of these rooms will be your office from now on, sir,” explains the British officer. “You will share it with a colleague. The rest of the house will be yours.”

From MOVING THE PALACE. Used with permission of New Vessel Press. Copyright © 2017 by Charif Majdalani.