Many of us are familiar with the second wave of feminism’s fights for birth control, abortion and equal pay, but you may be unfamiliar with something else activists battled for during the 1960s and 70s: the bar stool.

During the 1960s, gender discrimination was a widely accepted feature of the bar. It was ubiquitous, like cheap beer and little bowls of salty snacks. Depending on the state, women were only allowed into bars at certain times, or only with male escorts, or sometimes, not at all. There were states where women couldn’t work in bars, even if they owned them.

The 1948 Supreme Court case of Goesaert v. Cleary upheld a Michigan law which prohibited women from bartending in all cities that had a population of 50,000 or more, unless their father or husband owned the establishment. The plaintiff in the case, Valentine Goesaert, owned a bar in Dearborn. She wanted to be able to bartend in her own goddamn bar and she wanted her female staff to be able to, as well. But Goesaert lost the case, because the court ruled that, since bartending could lead to “moral and social problems” for women, Michigan (and any other state) had the power to prohibit them from being bartenders.

Sound like bullshit? It is, of course. Unfortunately, it’s bullshit that predates bars themselves.

At the time Goesaert v. Cleary was being decided, gendered drinking discrimination had been around for over a thousand years. Since the days of Babylon, in cultures all over the world, women were not allowed to drink in public, or at all. In the early days of Rome, women could be put to death if they were found drinking.

This ancient sexism also masked itself with concern for “moral and social problems”. In the code of Hammurabi—the legal document that essentially established the patriarchy— it was written that “godly” women could not drink. It came from the male fear that women would act like people, instead of like property. The code of Hammurabi set in stone that women and their reproductive rights were the property of men, either fathers or husbands. If a woman went off to party and drink, she might have a fling that resulted in the loss of her virginity, a direct financial blow to her husband or father. It wasn’t about morals. It was about control.

So, public drinking culture, with some exceptions, developed over the centuries as a mostly male space. By the time bars as we know them today started popping up in America, “women shouldn’t drink in public” was an accepted social rule, just like “everyone should wear clothes.”

Until one December evening in 1967.

On that night in Syracuse, New York, a journalism student named Joan Kennedy had just finished Christmas shopping with her mother, and the two women decided to go into the bar at the Hotel Syracuse. The bar, named The Rainbow Lounge, denied them entry on the grounds that they were without male escorts. Kennedy was furious.

Soon afterwards, she approached Karen DeCrow, who was then a law student active in the brand spanking new chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in Syracuse.

At first, NOW had a lot of internal disagreement about whether it should be a priority for the organization to make the barstool a battleground for the women’s rights movement. Equal pay seemed to be a lofty pursuit, but was having a beer in public just as lofty? Lots of members didn’t think so.

DeCrow, however, did.

It seems trivial, being able to drink in a bar. But since the earliest days of civilization, the public watering hole was crucial to popular culture, to professional partnerships, to the creation of neighborly bonds, the maintenance of community, and the dissemination of news and local knowledge. A lot of important stuff happened at the tavern and the bar, a place where women were unwelcome.

DeCrow argued that going to a bar was a symbol of being a free person and a way to get women integrated into the workplace. She thought it was crucial for women to be able to leave the home and hang out in the public sphere, where networking and business meetings happened. Since so many states, cities and towns allowed discrimination behind the bar as well, it also kept a lot of women out of a potential job. In 1964, twenty-six states still prohibited women from bartending.

The rest of NOW eventually agreed with DeCrow, and then she launched a plan.

NOW activists traveled from all around the country to participate in a sit-in that she organized at The Rainbow Lounge. Unfortunately, the hotel was ready for them. The owners had taken precautionary measures—right before the protesters arrived, the hotel staff changed the numbers on the occupancy limit sign in the bar from 110 to 6. To top it off, they removed the seats from all the bar stools. It didn’t deter the NOW protesters, though. Afterwards, DeCrow issued a lawsuit against the Hotel Syracuse.

The next year, after a few more sit-ins, DeCrow brought the issue of gendered bar discrimination to the 1968 NOW Convention in New York City. The convention was held at the Biltmore Hotel, which was perfect for the point DeCrow was trying to make: the hotel had a men-only bar.

In February of the following year, DeCrow organized “Public Accommodations Week” with other members of NOW. Part of the week of activism and protests involved “drink-ins” at men-only bars across the entire country. At the Plaza Hotel’s Oak Room in New York City, Betty Friedan’s party of three was refused service by the bartender.

McSorley’s, a bar in Manhattan, had never served a woman in all 115 years of its existence. The bar sported a sign on its front door proclaiming, “No Back Room In Here For Ladies.” The owners were proud that they had “thrived for over a century on good ale, raw onions and no women.”

For DeCrow’s drink-in that week, she marched into the stinky atmosphere of McSorley’s with a group of fellow NOW members. The women were ignored by the bartenders and when one man tried to buy drinks for all of them, an angry crowd of men grabbed him and quite literally threw him out the door.

By the next year, NOW’s protests and drink-ins had finally paid off. In 1970, New York City law eliminated gender discrimination in all public places. Some bars refused to comply with the law and had to be forced to let women in. Some bars welcomed their new customers. Some tried to turn the whole affair into a publicity stunt, such as Berghoff’s, who publicly invited Gloria Steinem (and a whole bunch of media) to come and have a drink.

In 1976, the Goesaert v. Cleary decision was overturned by another discrimination case. Craig v. Boren started in Oklahoma, where 3.2 percent ABV beer was available for purchase by women at the age of eighteen, but not by men until the age of twenty-one. This was a holdover from the practice of women buying beer to bring home for their families. The thinking was that women needed to be able to bring home beer for their husbands and families to drink, but men only bought beer for themselves to drink. A 20-year-old man named Curtis Craig and a female liquor store owner named Carolyn Whitener agreed that the law needed to be changed. The two teamed up to challenge it in court.

The lawsuit was in rough shape until a brilliant legal counsel at the Women’s Rights Project at the ACLU offered some assistance. It was Ruth Bader Ginsburg, future Supreme Court justice herself. She wrote to the lawyer on the case, saying that she was “delighted to see the Supreme Court is interested in beer drinkers.”

With Ginsburg’s help, the case was argued successfully. The Supreme Court ruled that the Oklahoma law made unconstitutional gender classifications. With this ruling, a new standard for review in gender discrimination cases was set and Goesaert v. Cleary was overruled.

Next time you have a beer, raise your glass to Karen DeCrow, second wave feminists, and RBG.

___________________________________________________

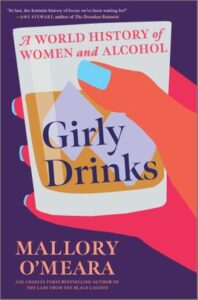

Mallory O’Meara’s Girly Drinks: A World History of Women and Alcohol will be published by Hanover Square Press on October 19, 2021.