The little girl’s case became a topic of conversation on the street and in offices and homes. Thanks to their privilege, the Miranda Felipe family had been able to get special treatment from the police and space on the front page of the biggest newspaper in the country. If their case was being discussed on a national level, why wasn’t the same thing happening for all the other kidnapped children? The waters were stagnant on one side and rushing on the other. Gloria Miranda Felipe’s case sparked exchanges about the wave of kidnappings on the radio. Word spread on public transportation and in upper-middle-class households. How could this have happened to one of their own? There was talk of gangs from Tepito, from Japan, from South America; there was talk of criminal networks selling Mexican children in the United States and Europe after World War II. There was even speculation that some of those children were being sold in the North so military widows could claim bigger pensions. In those days, racism, classism, and xenophobia grew in the streets like grass pushing through cracks in the pavement. All it took was a mother and her child passing someone with darker skin, “an oriental” or “a gypsy,” to unleash all sorts of violent speech.

It was a hot topic, even more so because the killing of a minor had been all over the news that week. A man had taken the life of a four-year-old boy in broad daylight, right in front of a café on Calle Tacuba. The guilty party said that he had meant to rob the child’s mother and that the death had been an accident. The Kiddie Killer, as one headline called him—and the name spread like wildfire—was in Lecumberri Prison, known also at the time as the Black Palace. The court’s verdict clarified that the Kiddie Killer’s intention had not been to rob the child’s mother but rather to murder the child, and that he was also guilty of murdering five other children, whom he buried in his garden.

Nuria Valencia had heard about the case a few days earlier on the radio she shared with Constanza, her coworker at a cardiologist’s office in Mexico’s General Hospital. Nuria, who had a young daughter, wondered what pleasure a killer might derive from murder. And, even worse, what pleasure a child killer might derive from the act. How could it be possible to kill a child and feel some kind of pleasure?

Nuria Valencia learned of Gloria Miranda Felipe’s kidnapping while listening to the radio in her kitchen. In the time it took to pour herself a glass of water, she decided that no information about the case would enter her house where she lived with her daughter, husband, and parents, so she locked the radio away in a sideboard in the living room. The little girl was already quite sheltered, and hiding the radio seemed a bit extreme to Nuria’s father, Gonzalo Valencia, but he had seen his daughter make decisions based on fear before and he understood her perspective.

Nuria Valencia had been trying for years to get pregnant with her husband, Martín Fernández Mendía, who was slightly older than her. Before their daughter Agustina arrived, they had fought often. Once, Martín even threatened to leave her if she didn’t get pregnant. He longed to be a father; he wanted a family and was tired of waiting. Agustina Mendía, Martín’s mother, had been insinuating for years that he should leave Nuria, though that would have been the case whether or not they’d started a family years earlier; it also would have been the case no matter whom Martín had chosen as his wife. Nuria Valencia Pérez had visited several gynecologists and one endocrinologist in recent years, when her need to get pregnant grew ever more pressing. It was a sensitive topic for the couple, more so as time wore on. Both wanted to be parents, but it simply wasn’t happening. Each of these doctors, all of whom were men over the age of fifty, said she was sterile, until one of them, using an innovative technique, diagnosed her with an obstruction of the Fallopian tubes that impeded the movement of her eggs and proposed a treatment that involved filling her uterus with gases to unblock her tubes, at which point her eggs would be freed from her ovaries, ready to be fertilized.

Nuria Valencia went to five sessions of this gas therapy. The doctor had prepared a calendar of the dates Nuria and Martín should try to get pregnant, and she followed the schedule to the letter, even if neither of them had any desire to sleep together. The first time she received the treatment, she let out several yelps and got so dizzy from the pain that she nearly fainted. The second time, she vomited in the bathroom of the doctor’s office. The third time, she did faint.

The fourth time, too. Her husband had to get her; he had been in a meeting in the offices of the movie theater where he worked when a nurse called to say that they had been unable to finish the procedure because his wife had lost consciousness. The fifth time, Nuria took several painkillers before leaving work and afterward had a migraine that stayed with her until the following night. The sixth time, having seen no results despite the extreme pain she had come to know so well, she gave up on the treatment and, without telling her husband, took a taxi from the clinic to the orphanage she had seen on her way to the hospital where she worked. She was going to fill out the paperwork necessary to begin the adoption process.

Mexico is famous for its lines and bureaucracy. It always has been. The paperwork required for an adoption, like so many other processes, was a labyrinth with no apparent way in or out; it wasn’t even clear there was a Minotaur at its center. After a few more cycles during which she didn’t get pregnant, Nuria had a talk with Martín. She proposed that they consider adopting and, contrary to her expectations, he was open to the idea. He told her, sincerely, that he was willing to forgo having a firstborn who looked like him and added, for the first time since that terrible fight, that he wanted to make a family with her. But if we’re going to adopt, he said, we’re adopting a boy so we can name him Martín Fernández, just like me. Nuria found it strange that this was her husband’s first concern, given that the other person with that name, his father, had abandoned him and his mother. Especially knowing that there already was another Martín Fernández, besides him and his father: the son of the woman he’d left Martín’s mother for. He’d named the boy after himself as if he were trading in his firstborn for this other child. The child who had grown up with a father. Why was her husband’s first paternal impulse so much like his father’s?

Adopting a newborn was a complex process in which the applicants had no say over the child’s biological gender. Martín left the bureaucracy to Nuria. They would talk at night about how things were going, and after a period of waiting they couldn’t characterize as long or short, they managed to adopt not a little boy, as Martín had wished, but a little girl—their daughter, Agustina Fernández Valencia. Martín had suggested that, while they sorted out the paperwork, Nuria could fake a pregnancy with a pillow so their friends would think the baby was biologically theirs. Not only did this idea not make much sense, but the date of the adoption was moved up so Martín abandoned the idea and instead proposed, or rather imposed, that they name the girl after his mother.

__________________________________

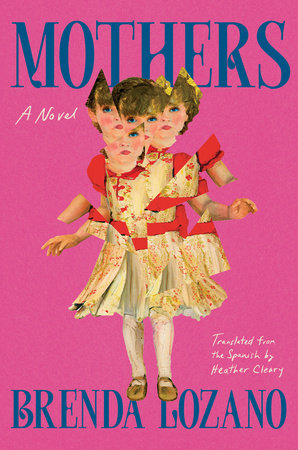

From Mothers by Brenda Lozano, translated by Heather Cleary. Used with permission of the publisher, Catapult. Copyright © 2025 by Brenda Lozano. Translation copyright © 2025 by Heather Cleary.