Mother Tongues: Reflections on Memory, Language, and Love in Germany

Tamar Shapiro: “I owe this book to my mother. It is not about her, and yet she is on every page.”

I worry that I am forgetting my mother. If anyone asked, I would tell them she was funny, a bit raucous, sharp and direct, immensely warm. I would say it was her irreverence I loved most. Or maybe her hugs. But these are just words. Even when I’m next to her, holding her hand as we walk toward the reed-fringed pond behind her memory care home, I struggle to summon what she was once like.

My husband tells me not to worry. He says he remembers. He will tell me all about her when I’m ready. I am grateful that he loves her, and then I am horrified. How shameful that he so easily remembers her, but I do not. I try to tell myself it is because I am too close, peering at the pixels of a photograph, grasping for a shape.

When I call home, my mother’s voice is still on my father’s machine. Despite my father’s complaints about the phone—so old, such bad sound quality—he hasn’t replaced it, and I am glad. I love listening to the German accent she never lost though her English was perfect. How funny, I think, that my parents gave me a name my mother couldn’t pronounce, always softening the hard “ay” I use for the first syllable, dropping the sharp r at the end.

Now she no longer knows I am her daughter, but when we speak German, it feels like I am her child again.

Now she rarely says my name, and I want more than anything to hear it.

*

My mother speaks German in memory care. She moved there when my father could no longer manage at home after three years of full-time caregiving. And yet, letting her go was a torment. Since then, he takes the bus to visit her daily, and each time he walks into her room, she lights up. If I happen to be there, she leans toward me, points at my father and tells me how handsome he is, whispering the broken half-words as if they were a delicious secret. Once, in a lucid moment on the way to a coffee shop, she grabbed my arm, pointed at my father a few steps ahead, and said, Er hat einen schönen Po! He has a nice behind! Then she laughed and held my arm tight. I collect these moments, these shining fragments of her.

*

My body has always turned toward the sound of German. I know, of course, what people think of the language, but everything in me reaches toward it. I do a double-take, an involuntary twist when I pass someone speaking German. I scroll social media pausing too long on posts about German dialects. Now the algorithm gods send me endless memes mocking the sound of the language I love, the language of my mother, my aunts, my grandmother. And I laugh at these memes just as my German mother, a reckless, wide-mouth, head-back laugher, would have laughed. I am reminded of the joke my father sometimes tells. What’s the word for butterfly? Papillon, croons the Frenchman. Mariposa, sings the Spaniard. Farfalla, warbles the Italian. And vat’s the metter viz Schmetterling?

One time, before a visit, my father asked me to make an effort to speak English so my mother wouldn’t forget. But I don’t make that effort. Instead, when I visit her, we chat in this new language that is German and yet isn’t. That is like a conversation and yet not. I do this, because the sound of German—even nonsensical German—is a connection to who my mother used to be. Just over a year ago, when she still sometimes spoke in full sentences, she told me she loved me. Then she said: Ich versuch’ das nicht zu vergessen. I am trying not to forget that. Now she no longer knows I am her daughter, but when we speak German, it feels like I am her child again.

*

My parents moved to Leipzig, Germany in 1994. My mother couldn’t wait to return to Germany after decades in Illinois far from her family. But it turned out to be not so much a return as an arrival in a different country with the same name. Forty years of separation between East and West had left their mark, had made my mother—who’d grown up in West Germany—a stranger in this East German city she had hoped would feel like home.

Still, over the many years they lived there, my parents grew to love Leipzig more deeply than any other place they’d lived, and I—a frequent visitor and explorer of its parks and forests, its bike paths, canals, and cafes—came to love it too. There was an informality to Leipzig that drew me in. The way summertime was enough of a reason for people to go barefoot, not just in the park, but on the street, in the grocery stores, to the cafe. The way time seemed to move more slowly, molasses afternoons giving way to hushed evening chatter. Finally, in 2017, my husband, kids and I moved to Leipzig for a few years ourselves. I’d lived in Germany many times before, at the Bodensee, in Bonn, in Berlin. But this felt different. This was a chance to give my kids what my parents had given me: a second home.

*

It was during the early days of our stay in Leipzig that my mother first confessed she was worried. We were on a bus headed home from a family friend’s funeral when she put her hand on my arm, the hand with which she had moments earlier tossed a white flower into that friend’s grave in the lush-green, graveled cemetery of my new city, and told me, in German, I’m worried I’m losing my memory. It didn’t strike me then, the parallel—my mother beginning to lose her memory in a part of Germany that had lost its past, decades wiped away almost overnight when East and West reunified. I wasn’t thinking about anything so abstract. I told my mother I was sure she was wrong, and I hoped desperately that I was right. I wished that the feeling of her hand on my arm, the fear in her eyes and the dread in my stomach would come to mean nothing—no metaphor, no meaning, no prediction. Nothing to remember at all.

Instead, I remember that moment often. How hesitant she seemed, as if voicing her fears might make them true. How she mentioned her own mother’s struggle with dementia, those final years when they were so far apart, my grandmother at her home in Wuppertal, my mother in Illinois. Thinking of my grandmother then reminds me of my mother’s six siblings, whose names she occasionally still calls out, though mostly, she has forgotten them too. She was excited to see more of them when she and my father moved from Illinois to Leipzig. She hoped they might visit frequently from the West, might be eager to explore the East together, to discover this place that was and wasn’t familiar. But the invisible boundary between East and West was stronger than she had imagined, and the visits were few and far between.

*

My own two years in Leipzig were all about removing boundaries. About showing my children how to live in a new place where leaves crunch underfoot on uneven cobblestones and the woody scent of linden trees fills the air, where we perched on the windowsill of the Späti across the street, eating ice cream on endless summer nights. And above all, a place where my kids were surrounded by my mother’s language, so their bodies would one day twist toward its sound too.

The removal of boundaries was also my preoccupation in a more literal sense. I’d long wanted to write a novel, but it wasn’t until those years in Leipzig that I actually began to draft the story of Kate and Martin, siblings caught up in a property dispute after German reunification. The complexity of a country splitting apart, then coming back together drew me in. The analogies too—how both countries and families can fall apart and find each other, how the damage lingers and perhaps the hope too. These, I realized, would be my themes.

What began as a dream to write has become a stake in the ground: This is my place too.

I wrote the first draft in Leipzig’s coffee shops and beer gardens. Sometimes my mother would bike across town, find me in one of my favorite spots, and then we would chat for hours while I glanced at my watch. When would she leave? When could I start writing again? In our final months in Leipzig, I stopped glancing at my watch, repressed the urge to return to writing. Instead, I biked home with her, joined her on the balcony for a cup of strong coffee. I knew this was likely my last chance to have my parents this close by. I saw, too, how quickly my mother was changing. Sometimes my kids came along, eager to eat the apple pancakes that were her specialty, the ones she could make in her sleep. “Remind me,” she said to my daughter one day, her hands holding the flour uncertainly over the bowl, “What do I do next?”

*

Now my mother doesn’t remember any of the places we’ve experienced together in Germany. She doesn’t remember taking the train from Leipzig to Grimma to hike down the Mulde, stopping for a creamy piece of Käsesahnetorte. She doesn’t remember lying under weeping willows at the Bodensee after a swim, our wet skin slowly warming, or foraging for beech nuts on the Venusberg in Bonn, their taste bittersweet on our tongues. All these places have vanished from her mind, and I can’t help worrying. Will my connection to my second home fray along with her memories of Germany, my memories of her?

We return to Leipzig every summer, like clockwork, but my connection to Germany is constantly changing, deepening with each arrival, growing more distant with each departure. My German ebbs and flows too. No matter how fluent I consider myself, my language still grows rusty with long absences. And yet, each time I return, the feeling of home hits me all over again. From the airplane, my eyes trace the familiar pattern—tight villages encircled by fields and woodlands. Once landed, I soak in the soft, full vowels of my second language, the smell of bread and coffee. There’s even something undefinably familiar about the air. Standing on the train quay, I breathe in deeply, knowing I am finally back.

For the past few years, working on my novel has helped bridge the time from departure to return, kept me immersed in Germany even when far away. What began as a dream to write has become a stake in the ground: This is my place too. I shouldn’t be surprised, then, that people want to know: How much of it is true? There are many correct answers, but I usually keep it simple: The settings are places I love, but the story is not my family’s story.

The most meaningful answer, however, is that I owe this book to my mother. It is not about her, and yet she is on every page. She gave me a second country, a second language, my love of German traditions, and my German family—the only extended family I ever really knew. A few months ago, I showed her a pre-publication copy of my novel. She held it tentatively, smoothed her fingers over the words. After a long pause, she said, Ich kenne das. I know this. I am not sure what she meant. These days I rarely am. Maybe she simply meant, this is something familiar. Maybe she meant, this is a book. Maybe she meant, this is your book. I will never know, and yet I am grateful that my mother—who gave me my German story—was able to hold the book she made possible in her hands.

__________________________________

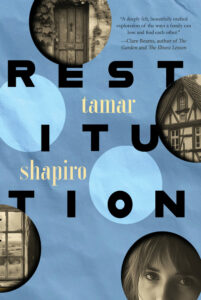

Restitution by Tamar Shapiro is available from Regal House Publishing.

Tamar Shapiro

Tamar Shapiro was raised in both the U.S. and Germany and now lives in Washington, DC with her husband, two children, and the world's best dog. While writing Restitution, Shapiro attended the Iowa Writers' Workshop Summer Program and the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference in Vermont. A former real estate attorney and non-profit leader, she is a 2026 MFA candidate at Randolph College in Virginia.