Mother or Weapon: Retired Cage Fighter Jenny Liou on Navigating the Body After Birth

“I feel silly even if I win, fresh off two babies, four years off the mats.”

At 6 a.m. on a Thursday, I stand in front of my mirror pinching and rolling the stiff white skin of my C-section scar back and forth between my fingertips. My belly flesh can’t really feel my touch, but a web of nervy pain buzzes through the numb skin of my abdomen. I release the scar and dig my fingers down into the two-inch space where my rectus abdominus muscles gape around my belly button.

I tuck my fingers into a fist and push harder, imagining I’m flat on my back with the full weight of an opponent’s body channeled through their knee. Unbidden, my mind’s eye sees that disembodied knee traveling straight through my body rent apart by carrying children before resting on the mats, not in a bloody and realistic way; more like some cheap movie rendering of someone colliding with a ghost.

I’m competing in a jiu jitsu tournament on Saturday, my first time competing in four years, after retiring from a career as a professional cage fighter before the birth of my children. So, on Thursday, it’s time to start doing the water cut to make weight, even though I guess I could just move up a weight class. After all, there’s no money on the line, no contract signed, and I don’t really care if I lose. But I’ve grown attached to the routine, the reassurance that my body is an instrument capable of doing what I ask.

Despite this confidence, my doctor sawed my firstborn out of my body and whisked him off to the NICU after 24 hours of unsuccessful labor. Because my pregnancy had been deemed low-risk, I’d been induced at a birthing center half an hour from the Auburn Hospital, so when they left with him, they left me behind, tethered to a catheter and to a steady drip of painkillers and antibiotics because my white blood cell count had skyrocketed after the surgery.

“Clear me, or I’ll just leave,” I told the on-call doctor, and an hour later, I walked unassisted into the hospital through the ER floor where 20 or so bloody teenagers were being stitched and splinted after what appeared to be some sort of gang-related brawl. My left brow hides a stitch line too, and my fingers swell and curve along the lines of fractures accrued throughout my many years of fighting in the cage, so I catch myself imagining the needle’s clean sting, the smell of white athletic tape releasing from the spool.

I wonder if other new mothers, with their innards held in by lines of taped-over staples and broad elastic bands, might have balked at the blood and fear and anger in that room, but it felt like home to me, and anyways, they stood between me and my new child, so I strode into their midst. Most of them relaxed their scowls and nudged each other backwards, clearing me a path.

Before our phone call ends, I ask her if it’s possible to be a mother and a weapon.

As I walked, trying to act as if I weren’t in pain, as if I weren’t about to cry over fear for my baby, or the trauma of our separation, I broke into a heavy, stinking sweat. It lasted all three days that I spent circling that brand new body in a bassinet in the hospital. By the time we took him home, he was healthy, my own infection had somehow disappeared, and I was already back down near my fighting weight. Indeed, I thought of the ordeal as the hardest fight of my career, one that had forged me, through suffering, into an even better kind of champion: a mother.

Two years later, my daughter joined us via a scheduled surgery, my doctor having recognized my body’s tendency to grow children broader than my hips, a direct repudiation of my confidence in my body as an instrument, but after seeing all the ultrasounds, what could I do but agree? He whisked her from my womb into my husband’s arms, cleaned the scarring from the prior emergency surgery, and less than an hour later, I was back in my hospital room, her new face pressed against my chest, FaceTiming my toddler and yearning to go home. And that was the beginning of slipping into a phase of gentleness I never knew I wanted.

The surgery never hurt, or rather, my sudden freedom from the tug and swell from the now-excised old scars so dramatically outweighed the sting of the clean new incision, that the second surgery felt like my own second birth, alongside my daughter’s. I never lost the baby weight. I never feared losing her. I never sweated out the stink of that fear. While COVID-19 raged around us, I nursed her, and held her, and took her toddler brother to the park, and taught him to ride a bicycle while she and I looked on. My shoulders softened. My cheeks broadened, but as I thought of my young son’s tendency to run unbidden into the ample arms of unknown and unsuspecting women, I thought maybe I’d gotten it wrong, that maybe I wanted or needed a big, soft mother’s body, one that my children would recognize as home.

It took a whole additional year, a new city, and my husband’s departure to a new job in another state, for me to start missing martial arts. But one day, I rode a wave of impulse back onto the mats, at a new gym, my purple belt so tight that I could barely tie it around me. There are all sorts of platitudes in martial arts about skill meaning more than strength, and in jiu jitsu, I really do believe these platitudes hold truth, and yet, it is also true that if you spend hours on the mats each day for years and years, your body marks the time with muscle, and muscle becomes synonymous with skill.

When I get home, I call my mother, fuming that, while my body may seem gentle now, I still have strength, and years of knowledge, and yet, I spent the whole class being condescended to by white belt men and childless women to whom my softness occluded my skill. My mother simply laughed and said, “Finally, this is your taste of living like the rest of us. You’re going to need to learn how to do a sport without being a star.”

My mother says she isn’t strong, although she was a swimmer and diver in college. She claims she gave it all up for us kids, that bearing us made her weight balloon and her hair fall out in bunches. But, even in her sixties, she accompanies me on many-mile bike rides through the rolling hills of the Palouse. On one of these rides, we were pursued by feral dogs. I was still at the peak of my fitness, but as they closed within the range of attack, before I could react, she shoved me back and started beating them with the steel frame of her bicycle. Before our phone call ends, I ask her if it’s possible to be a mother and a weapon. She laughs.

Now, six months back into training, I chug half a gallon of water in a single breath. This is the way that I used to cut weight throughout my professional fighting career. After trying to drink more than usual all week, on Thursday, you drink two gallons. It may seem counterintuitive to drink 16.6 gallons of water when you’re trying to lose weight, but your goal is to upregulate your endogenous diuretics—your body thinks you’re killing yourself with water, and frantically starts sweating and peeing it out. You also cut out all salt to shift your body’s osmotic balance, shedding even more fluid. This may sound unpleasant, and it is, but it’s a ritual, and one that I’ve grown so accustomed to that I can’t imagine preparing for a fight without it.

Friday, I don’t drink a thing. I put on a neoprene shirt and a thick hoody over it and run slow laps through the neighborhood pushing my kids in a double-jogging stroller. There’s a heat dome over Grit City, and the neighbors are gawking from their shaded porches. Before kids, I would have simply explained that I was getting ready for a fight, but somehow, in this body, pushing this stroller down the sidewalk, my explanation feels unbelievable, so I just let them stare.

For many years, I associated the routine of cutting weight with the smell of cedar because, for most of these weight cuts, I lost the final pounds in cedar-planked saunas. It felt so bright and clean, as if I were a muscle-gnarled tree and my sweat, rolling off in sheets were a monsoon, releasing all the landscape’s pent-up scents into the summer air. This time, I break into sweat, and I’m reminded of the sweet sick smell of the hospital, of nurses speaking just below what they think I can hear, my baby’s motions slowing on the examination table. I shudder, towel off, and stumble home.

The next morning, shortly before my fight, I discover that the tournament has decided to combine some of the women’s brackets. This sometimes happens because the women’s upper belts are often sparse, so, while men can expect to fight opponents who are similar in skill and age as well as weight, women are also compelled to fight younger or larger opponents. In this case, I’ve been shuffled into a bracket with a single opponent who outweighs me by more than twenty pounds. This means that instead of fighting different people all the way through the bracket, we’ll be doing the best out of three.

Some people like it when they get placed in tiny brackets because this means they’re guaranteed to medal. I hate it. I feel silly even if I win, and in this particular case, fresh off two babies, four years off the mats, and two rounds of abdominal surgery, a large opponent is my kryptonite. I keep imagining her forcing her knee into my belly so hard that my body disappears.

I broke into laughter in the middle of the fight, deep belly laughter.

“Jenny!” My coach raises his voice. “It’s time to start hunting for submissions.” There’s 30 seconds left in the final fight and I’m up 17 to two, at this point, an unclosable margin. I lost the first round exactly as I feared–she powered me to the ground, dug a knee into my abdomen and a shoulder into my throat, and I couldn’t get her off of me, so I lost the round on points. Between rounds, my coach told me that in the next round, if I got pinned like that, I could not think about what technique to use, her weight, or my vulnerabilities. I would need to stand up and out-muscle her no matter what. I would simply need to unleash the fury that I used to have. I kept looking past him to my daughter asleep in someone else’s arms.

The referee started the fight. Midway through the round, she slapped me across the face, which isn’t really legal, but didn’t get called. It woke me up. We locked arms and I felt her heavy breathing in my ear and realized she was tired, and I wasn’t yet. I felt that old surge of adrenaline, the once-familiar fight-time tunnel vision and took her to the ground, dragged her arm across her body, threw my leg across her neck into an armbar, and stretched her elbow to breaking point.

She tapped and it was over. I raised my gaze, looking for my son, and someone shouted that he’d gone off to nap behind the bleachers—my three-year-old all alone in that sea of spectators—how could I have trusted him to someone else? How could I have left him? The panic that poured over my body made me realize that even as I sunk that armbar, I had only been fighting with a tiny portion of my heart. And then my teammate clarified that he was sleeping as another of our teammates was watching over him, sacrificing her chance to watch the matches for my chance to compete. And so, we moved on to round three.

“Fight,” the referee exclaimed before my adrenaline faded, and I controlled her easily this time, moving from position to position, racking up points. Up by fifteen points with thirty seconds left, I kept seeing chances to submit her. The thing is, I was almost sure to win, and the only way I could imagine losing was attempting a submission, missing it, then getting caught in something.

And so, I heard my coach and other voices from the audience urging me to finish it, and as I realized that today, I was going to hold her down, to win by keeping things exactly as they were, I broke into laughter in the middle of the fight, deep belly laughter. I felt down to my suture lines, felt my stomach muscles strain but still hold fast, and me, in the middle of it all, not a blind or bloody weapon, just a healing body, barely strong enough to win, scanning the auditorium for my sleeping children, hurrying back to them.

__________________________________

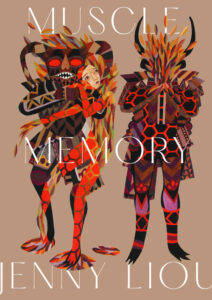

Muscle Memory by Jenny Liou is available via Kaya Press.

Jenny Liou

Jenny Liou is an English professor at Pierce College and a retired professional cage fighter. She lives and writes in Covington, Washington.