Moriel Rothman-Zecher on the Magic of Writing at Sunrise

“It is my job, simply, to open my eyes, and place my fingers on the keyboard and then, let go.”

The sky is silverish gray with hints of mauve. Next to my second-floor window, the Philadelphia streetlight glows like a lantern. The silhouettes of leaves are moving, just slightly, in the predawn breeze. The city is mostly quiet, with the occasional sound of car tires moving fast over wet pavement.

My dog, Gus, is nestled entirely under the blankets; in the other room of the apartment, my four-year-old daughter is still sleeping, and will, inshallah, stay asleep until 6:30, or even close to 7:00, if I’m lucky, at which point she’ll bound into my room and demand to type on my computer— “4u8uw98uq8iuyeiuakwijIhejpit0uq9ifpekoir9irwophieiuhfvoidjuqhfhnlih3giuyshntjqudhoiuihs” is an excerpt from yesterday’s work (“Aba, can you read to me what this says?”).

In the meantime, though, it’s just past 5:00 in the morning. I am sitting with a cup of coffee. My eyes are bleary, my mind is coated in a patina of memories, remnants of dreams, sounds, words. There is a part of me that longs, of course, to snuggle back under the blankets with Gus, to allow my daughter to function as my alarm clock. But instead, this morning, as on many, perhaps even most, weekday mornings for the past decade, I open a word document and begin to write.

The writer’s life, as I live it, is really only an hour or two long each day.

Elie Wiesel, in an interview with the Paris Review, described writing in the early morning as “a pleasant agony.” I love that formulation. I feel a deep, weighted placelessness for an hour, perhaps less, each morning; the solidity of this sensation is derived, at least in part, from the fact that it is not a particularly pleasant one.

Neither is it particularly unpleasant. It is a time/space in each of my days that is set off from the rest, in which my mind is not brimming with worries and plans and concepts and thoughts. Instead, it is mostly just words, words that come out onto the page not as I tell them to, but rather as they want to, or need to, if I allow myself—which I do less grudgingly at 5:00 in the morning—to wax a bit mystical.

A friend once asked me what it meant, practically, for me to be a writer. “What do your days look like? What do you do all day?” I responded that it meant that I write five days a week, from 5:00 am until 6:30 or so, and then from 6:30 am until 10:00 or 11:00 pm—I fret.

I was joking, sort of, or at least I used a jokesome voice as I said this, but it’s actually not an inaccurate portrait of many of my days. The writer’s life, as I live it, is really only an hour or two long each day. Occasionally three or four. Rarely more than that. The rest of my life is the parent’s life, or the writing teacher’s life, or the emailer’s life, or the translator’s life, or the freelance editor’s, or the dog wrangler’s, or the runner’s, or the grocery shopper’s, or the book tourer’s, on occasion, but it is only in those morning hours that I am truly able to write, consistently.

In that hour or so each morning, I do live a life that is centered around writing. This is precisely due to the fact that, at 5:00 am, I am barely me, or, rather, the Me is subordinate to the writing, to the art, to the fictional character’s desires, to the poem’s rhythm, to the fallowness or fulsomeness of particular sounds or consonants or syllables. (I resisted the temptation, as I wrote that sentence, to google the words “fallowness” and “fulsomeness” in order to make sure I was using them correctly—and that’s just it: at 5:00 am, my brain isn’t awake enough to be concerned with concepts of correct and incorrect, or, even worse, questions of Good Writing and Bad Writing).

This early morning writing time is magic, and it is mundane.

This early morning writing time is magic, and it is mundane, and a bit of googling —done earlier!— tells me that I am hardly alone in the writing world as an adherent. Czeslaw Milosz reported that “I write every morning, whether one line or more, but only in the morning.” Salman Rushdie said, “I don’t have any strange, occult practices. I just get up, go downstairs, and write. I’ve learned that I need to give it the first energy of the day, so before I read the newspaper, before I open the mail, before I phone anyone, often before I have a shower, I sit in my pajamas at the desk.”

Toni Morrison, who famously wrote much of The Bluest Eye while her two children were sleeping, spoke of writing “very early in the morning, before the sun comes up. Because I’m very smart at that time of day.” According to this delightful database, where I found each of these snippets, and which compiled data from interviews from The Paris Review, Goodreads, and elsewhere, other specific 5:00 am-ers have included Donald Hall, Rebecca Skloot, W. D. Snodgrass, and many more.

Jonathan Evison, another 5:00 am-er, addressed another aspect of this temporal bargain: “When you’re up at that time [I think], I better get some work done, otherwise I’m nuts to be up at this hour.” And Mary Oliver spoke to the (sort of) compatibility of this practice with a day job: “If anybody has a job and starts at 9, there’s no reason why they can’t get up at 4:30 or 5:00 and write for a couple of hours, and give their employers their second-best effort of the day—which is what I did.”

Most mornings, the last thing I want to do at 5:00 am is get out of bed and start writing; most mornings, at 6:30, I enter the rest of my day with an immense gratitude at having written. But anyway, by 5:15, once I’ve gotten started, I’m not really there anymore, so both my grudgingness before starting and my gratitude after the fact are both largely immaterial. The magic of the hour works on its own; it is my job, simply, to open my eyes, and place my fingers on the keyboard and then, let go.

This early morning writing is mundane, and it is magical. The poet Derek Walcott, another early riser and writer, said:

I love the cool darkness and the joy and the splendor of the sunrise coming up. I guess I would say, especially in the location of where I am, the early dark and the sunrise, and being up with the coffee and with whatever you’re working on, is a very ritualistic thing. I’d even go further and say it’s a religious thing. It has its instruments and its surroundings. And you can feel your own spirit waking.

And that’s just it. It’s the spirit waking, and it’s the body being awoken by a blaring iPhone alarm (on airplane mode, of course, so as to resist the temptations to glance at whatever notifications accrued overnight). It can be a transcendent practice, on the life-level, and it’s mostly a schlep on the daily one. When someone—a student, a friend, an acquaintance—asks me what advice I have for newer writers, my answers can often veer into the realm of pseudo-mystical psychobabble (I should put that on my resume as I search for academic creative writing jobs, yeah?).

But the concrete advice I do have is that a writer can benefit from a rigid schedule, which supersedes the daily debate of Should I Write Today. If I had to decide that question on a daily basis, most days, the forces of self-doubt, capitalism, parenting, sleepiness, Gmail and Apple Inc. would certainly co-conspire to call out a resounding, choral Hell No. So, I take that decision away from myself, so to speak, and establish a writing schedule that deprives my day-to-day self of say in the matter.

And if this interlocutor were to ask me a follow-up question, as to what this schedule might look like, I would suggest that they try getting their writing in before they’ve checked their phone, before they’ve glanced at their email, before they’ve really spoken to family members or partners, or extensively cared for pets, before they’ve fully exited the space of dreams and of exhaustion, in which the self hasn’t yet fully re-cohered into its daily performance, in which the words might wash over the writer, and rush out less filteredly, less sensibly, less reasonably, less predicably, less coherently; all of this can be shaped into a novel, a poem, a story at another hour, in a different time/space, say, some fine 9:00 pm or other.

In other words, I may apologetically grin and then suggest, quite seriously, that they give 5:00 am a shot.

__________________________________

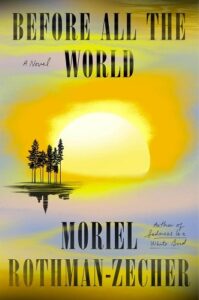

Before All the World by Moriel Rothman-Zecher is available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Moriel Rothman-Zecher

Moriel Rothman-Zecher is the author of the novels Sadness Is a White Bird, for which he received the National Book Foundation's '5 Under 35' honor, among other awards, and Before All the World, which was named an NPR Best Book of 2022. His poetry and essays have been published in The American Poetry Review, Barrelhouse, Colorado Review, The Common, Lit Hub, The New York Times, The Paris Review's Daily, Poetry Daily, Zyzzyva Magazine, and elsewhere, and he is the recipient of two MacDowell Fellowships for Literature. Moriel teaches creative writing as a Visiting Assistant Professor at Swarthmore College, and through the Bennington Writing Seminars' low residency MFA program. He lives in Philadelphia, and is currently working on a first book of poems and a third novel.